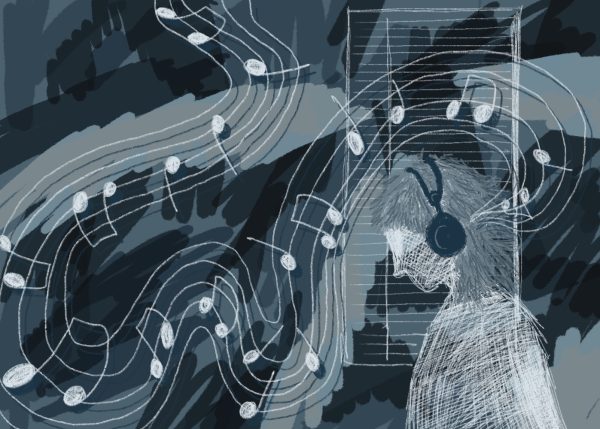

St. Vincent’s new album is an epic of self-reflection

November 10, 2017

Annie Clark has been deemed a contemporary “female Bowie,” by critics since she first began producing music as St. Vincent.

In her most recent album, she examines the personal veracity of an imposed on her – Bowie’s androgynous indie-pop successor.

Reviews of her album by esteemed music critics at major paint her album as a compass-rose of where music, and in particular pop music, will go after Bowie’s death.

Critics examine her lyrics sparingly, without much examination into the careful cultural allusions in her lyrics; they paint her similarly to the way she satirically paints herself on her album cover: a sexualized artistic female body with no face, given on a platter to be interpreted anyway that people want, instead of the complex themes of the person that lie beneath.

Clark’s title track, “Masseducation,” has been interpreted a “paradox” New York Times’ chief pop-music critic Jon Pareles, but fails to interpret the paradox as extended to Clark’s introspection, thereby erasing the personal and identity-based aspect of Clark’s newest masterpiece.

Her lyrics in the song “Masseducation” illuminate a personal and societal existential debacle of whether she — and contemporary artists in general — are seduced by fame into becoming what her viewers want her to be. The rest of the album contemplates whether this destroys the human parts of the contemporary artist themselves in their art and in their lives.

This is situated through allusions in the song. The final line of her first verse of this track places her album as a critique of the world’s perverse interpretation of cultural-icons: “Lolita is weeping” is the most telling of all Clark’s lyrics.

Lolita, a character in a book with the same name is the story told by an unreliable narrator Humbert Humbert, who paints a warped picture of a “relationship,” he has with his 12-year old stepdaughter. The novel has often been read as a critique of Americans’ ability to believe what they are told on the surface, even if it is clearly false.

Lolita represents mass misinterpretation of a character. Clark alludes to Lolita to draw parallels to herself and the character: the narrator of her life is unreliable and those that tell and hear her story can’t see that she is weeping.

Clark also harks back to a former self-destructive protagonist “Johnny,” first introduced in “Prince Johnny,” in 2013, a song that can be interpreted as one of her first about the limiting box of fame, with the famously bridging chorus: “so you pray to all, all, all to make you a real boy.”

Who Johnny is has been debated since Clark introduced him, but some have hypothesized him to be a part of Clark herself.

Her reference to “Johnny” brings the listener back to the themes of an addiction to the destruction of identity because of the high that comes from fame. If Johnny is an extension of Clark herself, the song ends with a haunting self-evaluation: “Annie, how can you do this to me?/Of course I blame me/when you get free Johnny, I hope you find peace.”

The album’s allusions to past loves, legends and cultural icons provide insight into Clark’s contemplation of her identity as an artist who has often danced along the line of gender identity and sexuality in front of the world in her art and in her private life.