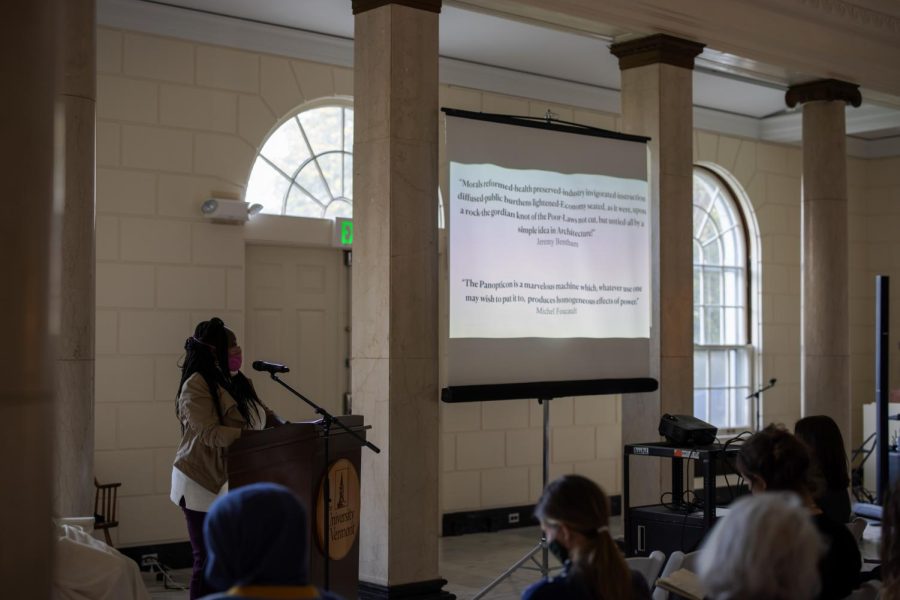

Artist Shanta Lee Gander speaks to a crowd in the Fleming Museum Nov. 5. Gander gives a lecture on issues of restitution.

Artists and scholars discuss problematic legacies of museums

November 8, 2021

Academics gathered in the Fleming Museum to discuss the problematic legacies of the artworks that hung on the walls around them.

On Nov. 4, a three-day conference opened in the Fleming Museum called “Repatriation/Restitution/Reparation,” where UVM faculty and visiting scholars discussed museum artifacts belonging to Indigenous communities and cultures.

This fall, the Fleming opened the museum in a process called, “The Fleming Reimagined,” which is an ongoing examination of the museum’s origin and purpose, according to the Fleming’s website. The symposium is an extension of this effort.

Vicki Brennan, religion professor and curator of the symposium, said the conference is part of a broader, global discussion of colonialism.

“Repatriation is returning these artifacts to the communities from which they were taken from,” she said. “Restitution is how we go forward while acknowledging the violent history of taking these objects.”

European museums have a long history of taking significant artifacts from colonized places, and showcasing those pieces perpetuates a harmful racial implication, Brennan said.

“Exhibits of African art in western museums tend to reinforce racialized assumptions about non-white people,” she said. “It is part of a larger project of white supremacy because it reinforces European superiority.”

Dan Hicks, professor of contemporary archaeology at Oxford University, was the keynote speaker on Nov. 4. After Hicks spoke, a round table discussion was held with scholars of art and religion from UVM.

A key event identified in the discussion was the Benin Massacre of 1897 in which British soldiers invaded the West-African nation and stole thousands of artworks, one of which sits in the Fleming today: the Queen Mother sculpture, the Fleming website stated.

However, repatriating and restituting is not enough to rectify colonial violence, Brennan said. Museums must also compensate those communities for the lasting effects inflicted upon them when taking these objects.

“Repatriation means repair,” she said. “It means providing payment for harms of the past.”

The second day of the conference focuses on the voices of artists and art historians, including interdisciplinary artist Shanta Lee Gardner.

Gander’s 2020 photo exhibit “Dark Goddess” explores cultural anthropology and aims to expand binary notions such as good and evil, according to her website. At the Fleming she discussed the connections between her work and the museum’s archives.

“After seeing an artifact, people think they understand the whole story,” Gander said. “But the truth is, we only know the context based on an ethnocentric perspective.”

Junior Lucy Heisey attended one of the Restitution talks at the symposium. She said accurate representation of cultures is crucial in museums.

“In many museums, cultures are often lumped together based on how we, as white people, perceive them,” she said. “We don’t get to understand all the different cultures and the peoples from which this artwork came from.”

Repatriation, restitution and reparation are the very first steps towards justice and a lot of work needs to be done, Gander said.

“This symposium is the first step that will be followed by many,” Gander said. “It is going to be uncomfortable because we are seeing the truth for the first time.”