Miles McCallum, president of UVM’s Black Student Union, poses with a 1988 poster for the union on Feb. 11.

The history of the Black Student Union

February 15, 2022

The Black Student Union creates a space of community for Black students at UVM, said senior Miles McCallum, president of the BSU.

Although formally recognized by the SGA in 2004, McCallum said BSU took many forms during its time at UVM. It carries on the traditions of its predecessors while also creating new traditions.

“Black students were organizing and making community whether or not formally recognized by SGA,” McCallum said. “That surely didn’t translate into just activism and activity that’s going to be recorded on the news but also in getting together and experiencing community together and making joy together.”

This history can be traced back to the ‘60s or ‘70s, times in which student activism was prevalent on campus, English Professor Nancy Walsh said, according to a March 2, 2016 Cynic article.

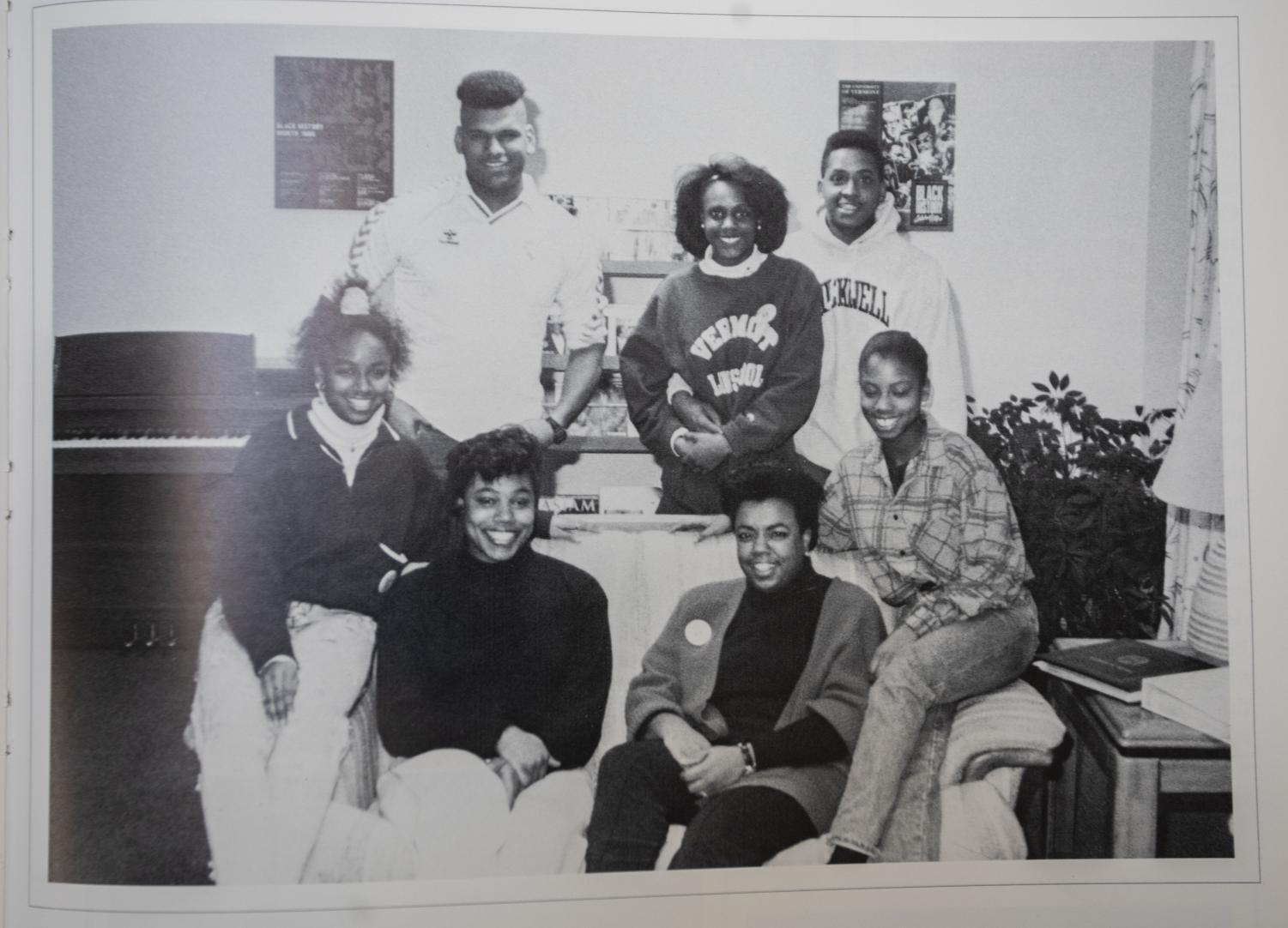

Beverly Colston, director of the Mosaic Center for Students of Color, said when she first joined the UVM community in 2000 she learned about the New Black Leaders, a previous iteration of BSU primarily active in the ‘90s.

“I’m sure that students created the New Black Leaders for similar reasons to why students created the BSU,” Colston said. “To make space for themselves in a place where you don’t see people that look like you and or your culture is not necessarily being celebrated.”

The legacy of Black student groups is not lost upon the current BSU. Although the group celebrates the community BSU provides, McCallum said he is also aware past obstacles are still relevant today.

Included in these obstacles is facing UVM’s long history of racism, McCallum said.

“I want BSU moving forward to be a unified rebuttal to that history,” McCallum said. “And to make space for the collective experience that is Blackness as personified and as lived by the Black undergraduate students here.”

Deciding how to take action on issues has also been key in how the BSU historically operates, Colston said.

“I believe that all of our clubs, including the BSU, and New Black Leaders in the past, also were spaces where students could determine how they wanted to combat racism,” Colston said.

Students have occupied Waterman three times in hopes of pushing the administration to act on issues of inclusion and diversity, according to a Feb. 26, 2019 Cynic article.

According to their respective lists of demands, all three takeovers included, but were not limited to, demands of an increase in the hiring and giving of tenure to faculty of color, more classes aimed at teaching diversity and the increase in accountability for racist remarks made on campus.

Historically BSU played large roles in each of these events and the frustrations of the takeovers are not unfamiliar to the BSU, McCallum said.

“I see myself in the tradition of the Waterman takeovers, we’re fighting the same battles because I don’t think the vision of those takeovers was fully brought to fruition,” McCallum said.

Additionally, BSU now faces challenges their predecessors never experienced. During the times of COVID-19, maintaining a sense of community over Zoom calls and restricted social gatherings has resulted in BSU searching for new ways to connect, McCallum said.

“The reality of the way that COVID-19 has disrupted things means that carrying on that tradition is a little bit more complicated,” McCallum said. “In terms of community turnover and in terms of participation and retention.”

Going forward, BSU finds strength in utilizing its traditions and history, Colston said.

“It’s inspiring to know that you come from a legacy where people are willing to basically step up and put themselves on the line for change,” Colston said.