Consolidation remains a constant reality for Vermont’s small schools

May 5, 2021

Tiffany Wilbur picked up her kids at Leicester Elementary, a school located a town over from their home in Whiting, VT. This is a new normal since the closure of Whiting elementary in 2018.

Vermont’s many small elementary schools play a large role in the communities of equally small towns. However, with recent consolidations of these schools as a result of Act 46, communities are changing.

In 2015, Vermont passed Act 46, a school governance reform that combined small school boards into a single union school district with one board.

Leicester, a small school ten minutes away from Whiting, became the receiving town for Whiting and Sudbury elementary school, two schools with less than 30 kids each.

Wilbur said the consolidation of the three schools made many parents angry, and some chose to send their kids to other schools, rather than to Leicester. Wilbur said she also felt emotional about the change.

“I was really hesitant in the beginning because so many people were being negative, but in the end I think the kids have really benefited from it,” said Wilbur.

Wilbur knew she liked the small school atmosphere of Whiting and was thankful that her kids were able to experience the same close knit community for a couple years.

“I fell in love with the small school. Everyone knew everyone. The kids treated each other like siblings,” Wilbur said.

However, Wilbur said with the consolidation her kids have more students in their classes allowing them to make more friends and connections.

Peter Conlon, House Representative and former Addison Central Supervisory District’s school board chair, said at a national level, schools are considered small if they have 200 students or less. But in the state of Vermont, numbers are much lower.

“That’s why I refer to them as very small schools. In our district some are under 80, some are under 50,” Conlon said.

Conlon said that schools with small numbers can mean less financial efficiency for a school district, resulting in school consolidations.

Conlon said Act 46 was meant to help the state’s education system, rather than hurt it.

“For most of the state, the particular challenge that continues to bedevil all school districts is declining enrollment,” Conlon said. “The result of Act 46 is that school districts unified and then began to take a more systematic look at their school districts.”

Wilbur said the main reason for Whiting’s closure was declining enrollment and excess costs.

Conlon said that Act 46 does not directly close and consolidate schools, but as a result of the consolidation of the school boards many newly unified boards have seen the need for financial efficiency and have made decisions to merge their small schools, including the closure of Whiting school.

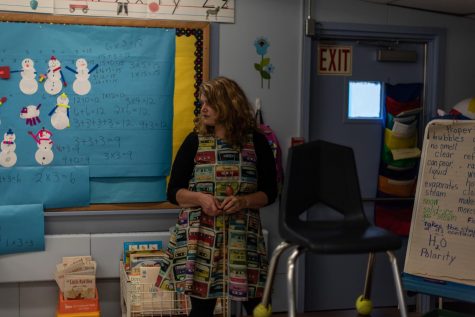

Kelli Blair worked for a number of years at Whiting elementary. For the majority of her time, she taught a combined classroom of kindergarten through second graders because of the lack of students. Now, she teaches second grade at Leicester.

Blair said she loves being a teacher in a small school.

“I loved the autonomy and the creativity that I had in such a small setting,” Blair said, “I really felt supported by the parents. If there was a problem, we worked together.”

However, with a transition to a different space and the inclusion of more students, Blair faced new challenges.

Blair said that in the consolidation process paperwork got lost and student files were disorganized resulting in the loss of academic and trauma plans for special needs students.

Blair said she is aware of the socioeconomic differences between Whiting and Leicester in ways the unified board does not see on a daily basis. She believes there is more the district could do to support the consolidated school.

“You are only as strong as your leaders, so there’s still major inequity. We have such a dense [amount of] poverty in our area,” Blair said.

Additionally, Blair said that with double the students in only a slightly larger space, there is no room for storage. The multipurpose room acts as both the interventionist space, gym, play area and lunchroom.

Conlon said that Act 46 was designed to provide benefits to small schools including merging collective resources to support students.

“We begin to think about these students as everyone’s students, because once they come together in a union middle or high school, they are all of our students,” Conlon said.

However, under the unified board, Blair said the school has less autonomy over staff decisions. She said the board took away an essential interventionist that worked with students with trauma.

With a lack of staff to serve low-income students with high levels of family related trauma and stress, Blair has helped fill the void by taking extra courses on trauma intervention on top of her normal workload.

A recent graduate of the UVM’s education program Carlie Reen ‘20, said that despite challenges like a lack of resources, new teachers like herself are often attracted to small schools.

“Something that really draws people in are the staff and the community. At least at the schools I’ve worked at the community is really involved and welcoming to new teachers,” Reen said.

Conlon said there were many financial benefits to combining governance. He said that student enrollment is declining in Vermont, and Act 46 was a way to combat small schools’ decreasing budget.

He also said that Act 46 is not just a choice.

“Act 46 did not just incentivize unified school districts, it required them, unless you could meet certain qualifications,” Conlon said.

However, in March, Addison County passed a vote to let Ripton elementary, one of seven small schools in the district, leave the district in order to avoid consolidation.

Tracy Harrington, Ripton’s principal said the community played a large role in this decision.

“Ripton was never a part of the equation in the decision-making process, and that wasn’t sitting well with community members so that was what started the effort to see if they could do something to save the school,” Harrington said.

The town voted to withdraw from the Addison Central district in January and in March the county approved the vote. The state still has to approve the decision in order for Ripton to officially become independent.

However, Harrington was the voice of opposition during this decision. She said she sees the challenges leaving the district could bring.

“The biggest thing is the cost of high-quality staff. It will be challenging to maintain high-quality staff in all specific fields for kids with specific needs. Those staffs are contracted and shared across the wider district,” Harrington said.

Conlon agrees with Harrington, as he said that budget strains will force many small schools into considering consolidation in the future.

“Financial pressure will continue to force school boards to look at not only the economic efficiencies of operating these very small schools but also the educational opportunities that may come with having schools of larger size,” Conlon said.

Wilbur said she makes an effort to be a part of her Leicester community, encouraging other parents to take a chance on the newly combined school, but she knows it’s not always easy.

“I really think it’s the unknown that makes consolidation so tough for people,” Wilbur said.