How “freshman 15” may contribute to diet culture on campus

October 14, 2021

The “freshman 15” is a familiar phrase to many first-years. This rhetoric may challenge students going through an already difficult transition into college, according to UVM dietitians.

The phrase “freshman 15” implies that first-year students will gain 15 pounds during the first year of college, unless they actively try to prevent it. The stereotype is detrimental for students’ mind-body connection, said Lizzy Pope, associate professor in the nutrition department and the director of the dietetics program.

“[Students] might hear that message ‘you are going to gain weight in college’, and suddenly stop trusting their body and start dieting,” said Amy Sercel, a registered dietitian with the Center for Student Wellbeing.

Diet culture encourages external rules about what people can and cannot eat, while attaching varying levels of value to certain body types according to the National Eating Disorders Association website.

As students navigate a new environment, they also begin to define health on their own terms for the first time, Pope said.

Moving to campus can create changes in nutrition and exercise habits, as well as introduce students to new ideas about food and their bodies that are both helpful and harmful, Pope said.

“People become very restrictive towards food either consciously or unconsciously, during the adjustment period,” said first-year Bella Sarnoff, a nutrition and food science major.

Sarnoff said she heard the phrase the “freshman 15” frequently as a first-year.

“[The freshman-15] is just ingrained in you when you become a freshman in college,” she said. “Whether people are joking or not, you will hear them talk about it.”

Saying the term more often normalizes a degrading message that ends up hurting people, Sarnoff said.

The expectation for students to actively resist weight gain may add external pressure to the transition students already experience.

The concept of the “freshman 15” stems from diet culture, Sercel said.

“I think anything that gets in the way of people trusting their own bodies can be really harmful,” she said.

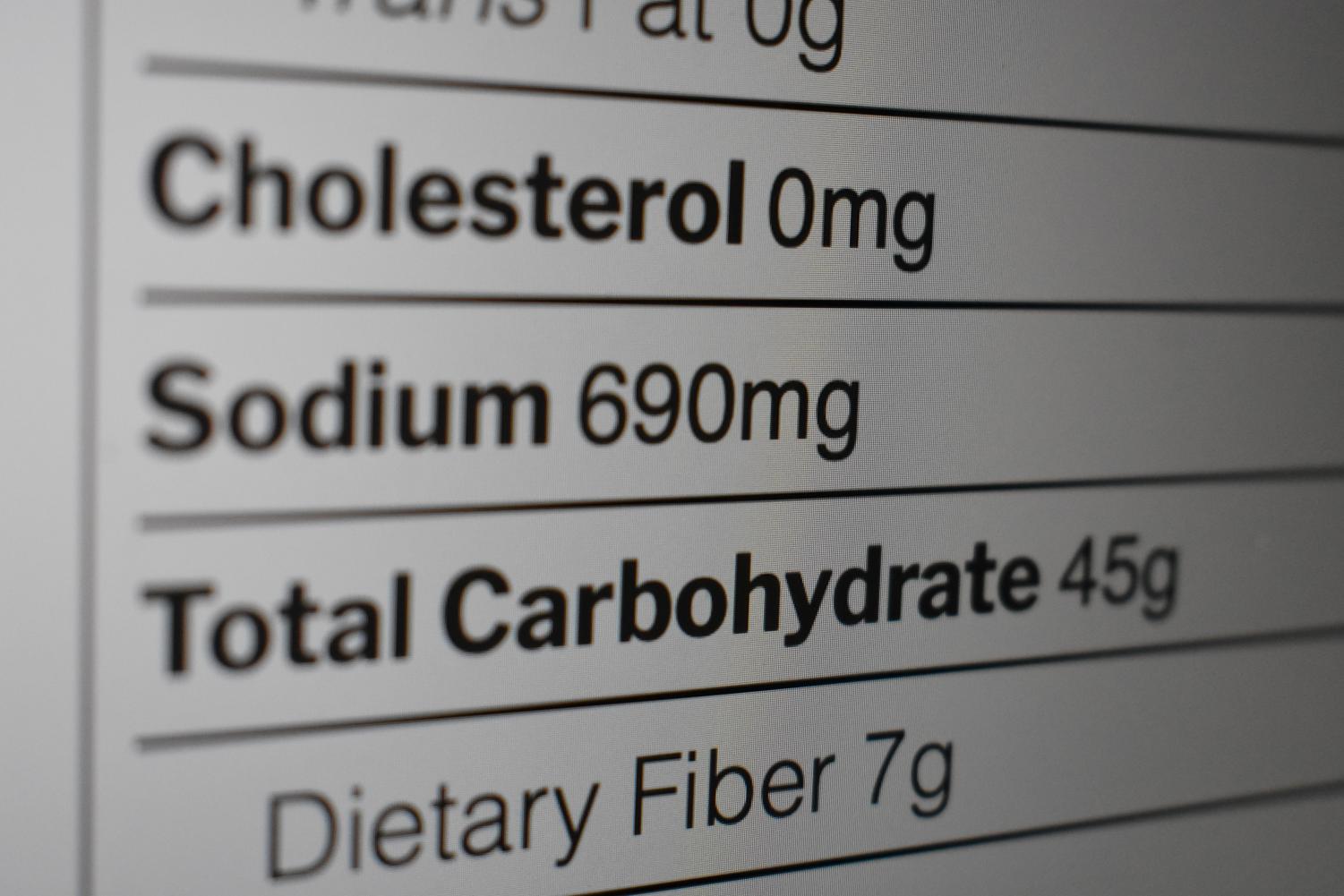

Pope said calorie counts listed on dining hall foods prevents students from listening to their bodies.

“If they did not have calorie labeling, that would be really positive for helping students develop a better relationship with food in terms of listening to their own body cues and their own interoceptive awareness,” Pope said.

Calorie labels can trigger someone with a history of dieting or disordered eating, and can also create new concerns about food for those who haven’t struggled, Sarnoff said.

Sarnoff said she experiences a mindset shift when she begins to calculate calories; she stops listening to her body’s cues.

Junior Livia Marchese said she doubts the accuracy of calorie labeling in the dining halls and the numbers impact her daily life.

“Once you see the number, it’s very hard to ignore it,” Marchese said.

Marchese, who experienced disordered eating in the past, said her focus on food and body image changed her perception of life.

“It’s just such a tough spot to be in, and it feels like all your worth is placed on how much you eat, or your body, and that’s just not a way to live your life,” she said.

Despite the glamorization of dieting, diets don’t work long term, Pope said.

The idea that larger bodies indicate poor health is not true, Sercel said.

The weight cycling process associated with dieting, in which people repeatedly lose and gain weight, is actually responsible for many of the health impacts that are traditionally associated with obesity, Sercel said.

Sercel said one solution to toxic diet culture is intuitive eating, a practice defined by Sercel as listening to hunger and fullness cues and unconditionally allowing oneself permission to eat.

“It’s never too late to heal your relationship with food,” Sarnoff said.