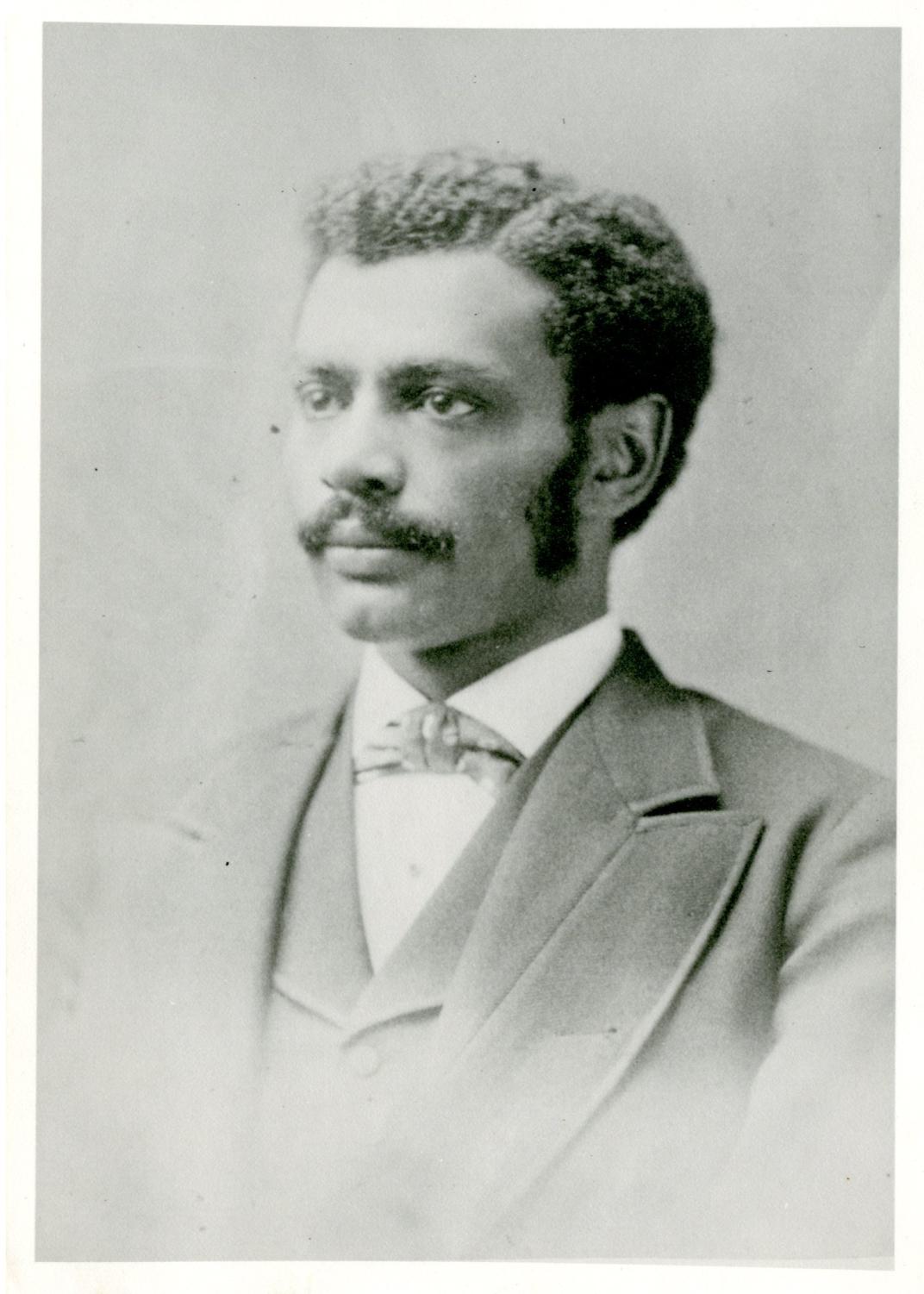

The story of George Washington Henderson

February 16, 2022

A formerly enslaved person, George Washingon Henderson, graduated at the top of UVM’s class of 1877, according to a 2001 Journal of Blacks in Higher Education article.

The UVM community regarded Henderson as the first Black graduate of UVM until 2004. Middlebury College archivist Bob Buckeye informed UVM archivist Jeff Marshall that it was actually Andrew Harris, abolitionist and 1838 graduate, according to an April 19, 2014 Burlington Free Press article.

Henderson was born on Nov. 16, 1850. Prior to his entrance into academia, he was enslaved in Clarke County, Virginia, according to an April 1968 Vermont Alumni Magazine article.

After the Civil War, Union Officer Byron Chandler Ward, class of 1865, brought Henderson to Underhill, Vermont, according to the 1968 article.

In Underhill, Henderson learned to read with the help of tutoring. Henderson’s schooling was not without hardship. Dr. W. Scott Nay, class of 1873, noted Henderson was frequently ridiculed by his classmates for his race, according to the article.

Henderson’s hard work and determination led him to admission to UVM in 1873 after just five years of study, according to the 1968 article.

During his undergraduate career, Henderson served as principal of Jericho Academy during his junior year and worked on local Vermont farms in his summers, according to the 2001 JBHE article.

Upon his graduation, prestigious honor society Phi Beta Kappa inducted Henderson in 1877. This made him the first Black student nation-wide to receive this distinction, according to the 2001 article.

At his graduation, Henderson presented a speech titled “The Economy of Moral Forces in History,” according to the 1968 article.

“[The speech’s] maturity and thought and good taste in presentation must be considered truly marvelous,” stated an 1877 Burlington Free Press article.

Proceeding his graduation, Henderson continued his studies, earning a Master of Arts in 1880 from UVM and a Bachelor of Divinity in 1883 from Yale Divinity School.

In 1896, he earned an honorary Doctor of Divinity from UVM, according to the 1968 article.

Henderson served as a teacher, minister, professor and principal in Vermont, all while he fought tirelessly for Black liberation. He also began teaching at Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1909, teaching ancient literature, Greek and Latin, according to a Nov. 8, 2010 Black Past article.

“[Black] education and [Black] suffrage were constant themes with Mr. Henderson throughout his life,” the Wilberforce Mirror stated.

Henderson contributed to the exposure of civil rights efforts, authoring his 1894 “The First Memorial Against Lynching,” the first substantial petition against lynching, according to the 2001 article.

Other works by Henderson include an 1898 pamphlet dedicated mainly to commemorating the troops that made significant contributions to the progress of America in the Spanish War, emphasizing the impact of the four Black regiments, the 2001 article stated.

In 1899, Henderson was elected to what was known as the American Negro Academy, yet quickly resigned due to his preoccupation with civil rights efforts, according to the 2001 article.

Henderson died in Wilberforce, Ohio on Feb. 6, 1936, according to the 2001 article.

Today, the George Washington Henderson Fellowship Program funds the studies of pre-doctoral and postdoctoral academics with historically marginalized racial and ethnic identities, according to the Office of the Provost. The goal of the Program is to promote intellectual diversity.

The recipients of the George Washington Henderson Fellowship include Dr. Sherwood Smith, CESS lecturer and director of the Center for Cultural Pluralism, and geography professor Pablo Bose, according to the Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

Bose rejects the common false sentiment that diversifying faculty means sacrificing instructor quality, according to a 2010 University Communications article.

“Everybody I have met who has been recruited through this program […] is of extremely high caliber,” Bose stated. “I think the biggest challenge for UVM is to hold onto them, not because of anything UVM has or doesn’t have but because we’re all very, very competitive candidates.”

Today, Smith is the senior executive director for Inclusive Excellence and Faculty Development in the Office of the Vice Provost for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

“I think the University has made some really good strides in my time here,” Smith said. “I don’t know that I would say [it’s] completely even across all the different programs and departments, as some have done better and some have done worse.”

In order to successfully diversify faculty, UVM must build a strong network before hiring and maintain a welcoming, inviting and supportive climate, Smith said.