A new perspective of some of UVM’s oldest displays

May 5, 2021

The back of a display case is a perspective relatively few people have the chance to see. To be able to see an exhibit in the same way the person who created it does feel magical.

It can reveal parts of the history that aren’t immediately visible from the outside – such as insights about the room it’s held in or when it was last changed.

This revelation is doubly true for collections that aren’t easily available to the public. Whether they’re actually displayed or not, the history behind items in a collection is always worth investigating.

At UVM in particular, many fascinating parts of the University’s history are kept as part of collections managed by specific departments.

For instance, the foyer of the Royall Tyler theatre features exhibits that capture highlights from performance classes at UVM.

“Of course, you know, in 1824 UVM burned down…and we lost everything, practically,” said scientific electronics technician David Hammond, about the collection of the physics department’s antique lab equipment and demonstration collection.

This exhibit still manages to capture a massive portion of the history of the sciences at UVM, with some surviving instruments being over a century and a half old, said Hammond.

That being said, the space it’s in is rather haphazard. In the move over from Cook Hall, it ended up being put in a room that has cycled its purpose many times.

While space concerns can force a collection of historic specimens into cramped, out-of-the-way locations, that doesn’t diminish their importance, both current and historical.

The Zadoch Thompson Zoological Collection is definitely one such exhibit, being tucked away into an unassuming building on Redstone Campus, the Blundell House, containing incredible examples of zoological research conducted at UVM.

In 2017 there was a fire in Torrey Hall, the previous location of the collection. Though the collection was mostly unharmed, the building itself was damaged and the collection had to be moved out.

Even if some parts of UVM’s history have been forgotten and some pieces of evidence have been lost or damaged, a remarkable amount of it has been preserved. Below are three collections which display that history.

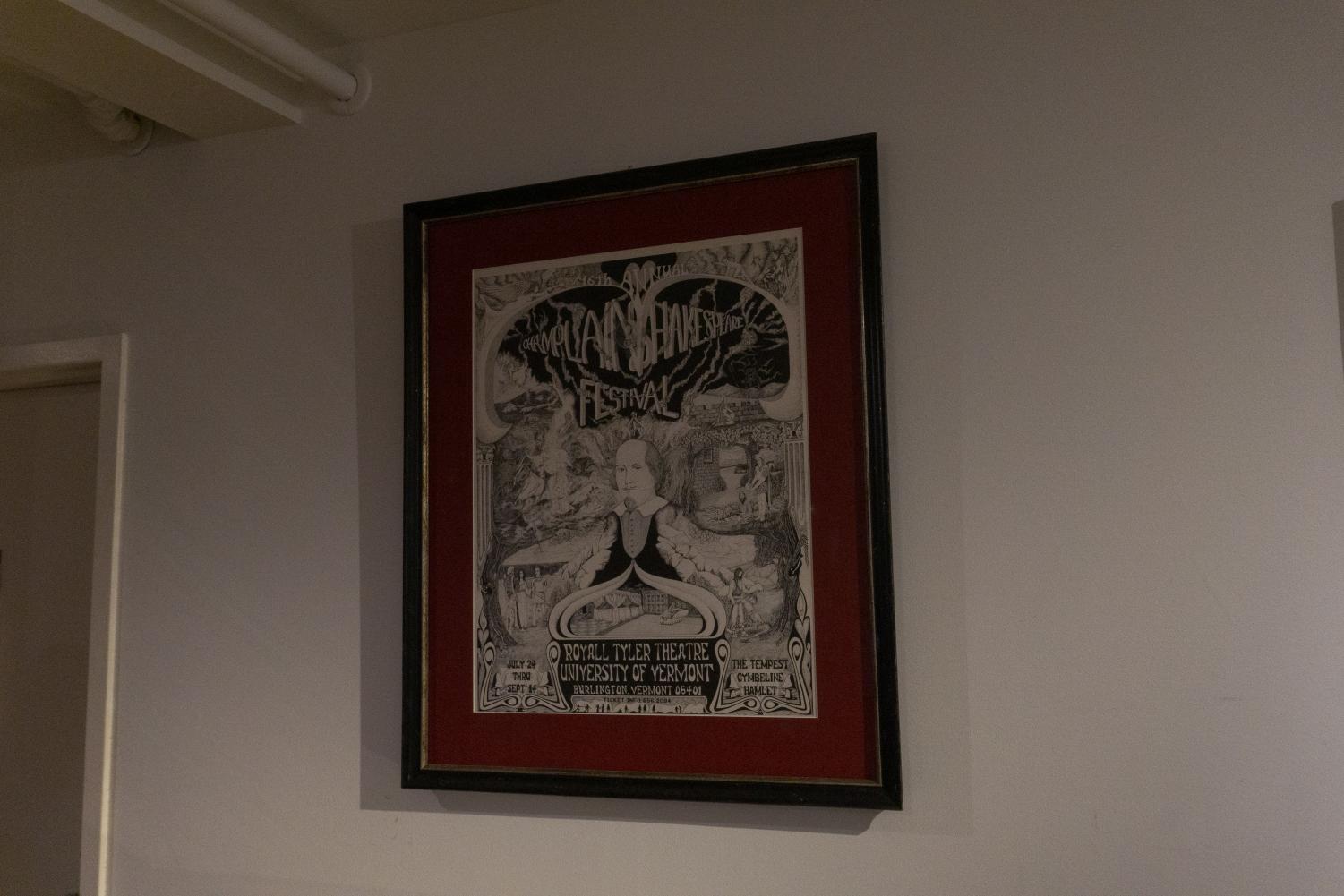

The foyer of the Royall Tyler Theatre has displays that show the history of the Theatre department. One of the current displays is a collection of posters from the Champlain Shakespeare Festival’s past performances.

The Champlain Shakespeare Festival began in 1959, according to the Shakespeare Quarterly. It ran until the mid-90s in the Royall Tyler Theatre, said Wayne Tetrick, Marketing and Administrative Coordinator for the UVM theatre and dance department.

Students performed Shakespeare plays, directed by both UVM professors and professors from other institutions.

Inside the main entrance stands two large dresses designed by Professor Martin Thaler and created by UVM students for the fall 2018 production of “Tartuffe,” said Tetrick.

Typically, the featured displays within the theatre are changed regularly, said Tetrick.

“It’s come to a halt because of the pandemic, this past year, but as we move into next year, as we return to whatever it is, a new normal, the old normal, we’ll do some different decorations in here … give it a new fresh look,” said Tetrick.

The oldest object in the collection is an oil lamp used in “Macbeth” during Helena Modjeska’s farewell tour of the U.S. from 1905 to 1906. A plaque at the base lists its previous owners.

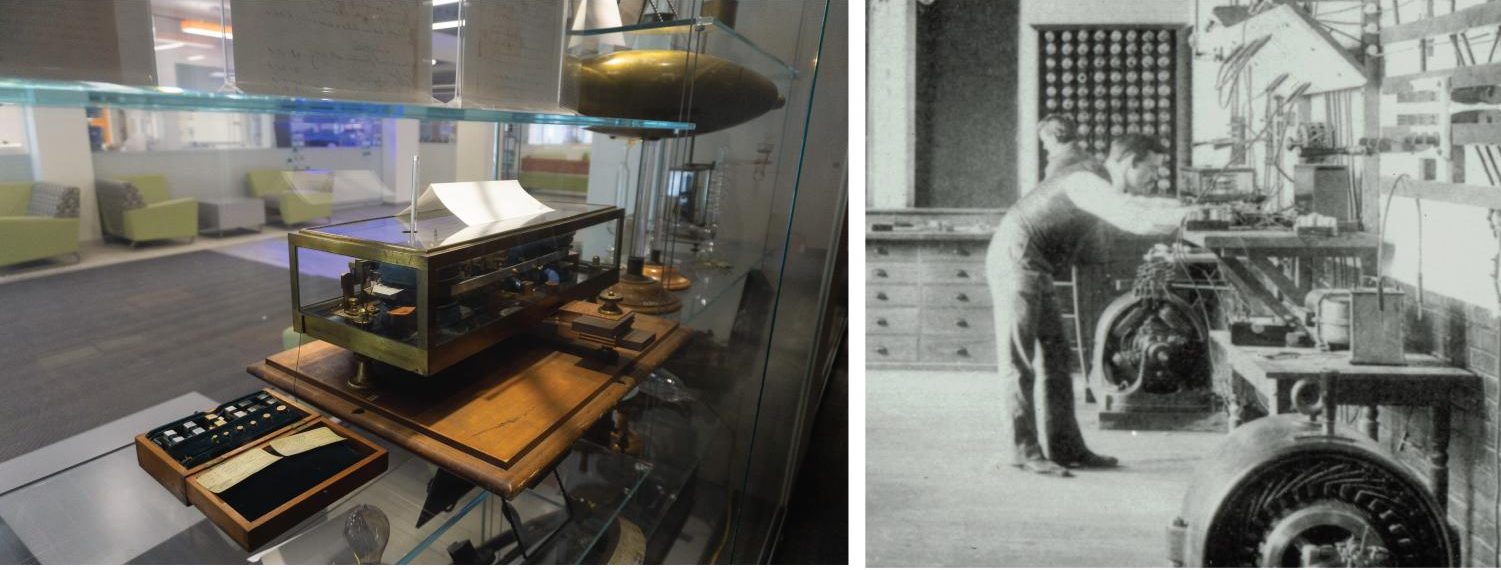

The physics department’s display case in Discovery Hall, as seen from behind. Originally collected in Cook Hall in 2001, the collection holds instruments from as far back as 1841.

Left: Discovery Hall displays a balance, a tool used to measure the difference between two electrical currents

Right: A film photo of a dynamo lab in Williams Hall, taken in the late 1890s. The picture shows a researcher using the balance that is now on display.

A set of electromagnets from the 1850s are displayed in Discovery Hall. The electromagnet in the center was constructed by the instrument maker Daniel Davis Jr. in Boston.

“Like the Sargent Welch catalog, or any scientific, educational catalog. He was kinda the first to do it in the U.S.,” Hammond said.

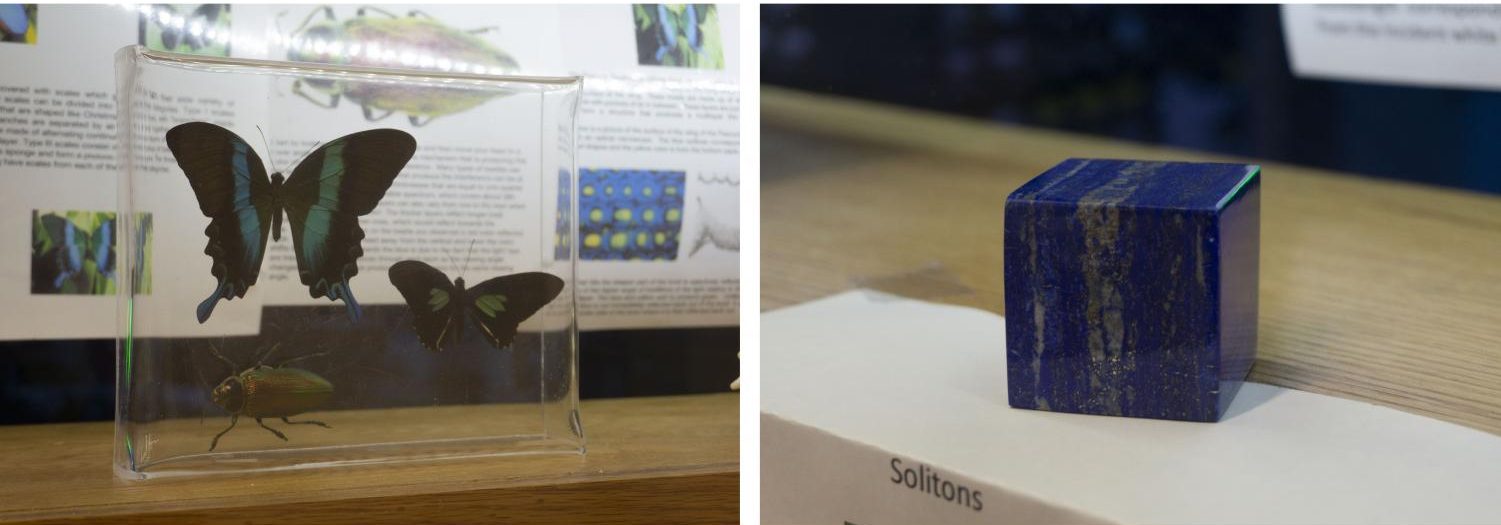

Right: A sample of lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone that has been valued for its blue color.

Left: A selection of insects also displaying blue coloring.

A separate display in Discovery Hall on the third floor shows a few physical phenomena – this section, in particular, shows structural coloration.

The lapis lazuli gets its color from the chemicals it contains, whereas the insects get their color from microscopic structures on the surface of their bodies which refract light. If you crushed the stone into a powder it would still retain its blue color, whereas if you crushed the insects, it would lose the color, according to an August 2014 Harvard Magazine article.

Though it’s an interesting scientific phenomenon, structural coloration is also what makes some of the invertebrate section of the Zadoch Thompson collection so beautiful. The striking blue color of the butterfly on the right hand side is a result of structural coloration.

These large beetles are rhinoceros beetles, a subfamily of beetles that are known for their large horns. Adults of some species can lift up to 850 times their body weight, according to a National Wildlife Federation article.

Along with a collection of invertebrates, the collection holds many vertebrate specimens.

Most of the Zadoch Thompson collection is not publicly displayed. However, a lot of it is used for educational purposes, such as this collection of wasps from around the world with the country of origin listed, which would likely have been used as a display for a zoology class, Curatorial Associate Sonia DeYoung said.

The one part of the Zadoch Thompson that is shown in an exhibit outside Benedict Auditorium in Marsh Life Science are a series of somewhat poorly maintained taxidermied animals.

The catamount is in such bad shape because prior to its installation here, it was used as a mascot, and the eyes installed in it are actually not meant for a taxidermied cougar, but rather for a taxidermied owl, according to a 1951 Burlington Free Press article.

However, the Biology department plans to have some restoration done on these very soon, DeYoung stated in an April 15 email.

“They’ll all be cleaned and the most damaged will be restored this summer through a grant from the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services,” stated DeYoung in the same email.