Xanax on Campus

May 1, 2018

Photo Illustration/ Alek Fleury and Genevieve Winn

Photo Illustration/ Alek Fleury and Genevieve Winn

First-year Joe Smith, a pseudonym, popped four bars of Xanax at 1 a.m. one Friday. The next thing he knew he was lying in his Harris Millis dorm bed, 40 hours and nine bars later, at 5 p.m. that Saturday.

He had attended two Friday morning engineering classes and spent Saturday afternoon skiing with his brother, but he had no memory of either.

“I don’t remember shit until Saturday the next day,” Smith said. “I lost an entire Friday.”

Recreational Xanax use and cases like Smith’s have become increasingly common at UVM, said Tom Fontana, who counsels students on substance use.

Xanax, a medication in the class of benzodiazepine, is almost exclusively prescribed for anxiety, said Dr. Michael Upton, a Counseling and Psychiatry services staff psychiatrist.

Fontana’s observations are consistent with national trends, documented in a recent American Public Health Association study that revealed that fatal overdoses of benzodiazepines increased more than 525 percent between 2000 and 2013.

“I’ve been working here for four or five years and its started to play a more prominent role over the last couple years,” Fontana said. “It occured to me that it’s kind of the drug students are most worried about, that the staff are most clueless about.”

The pill comes in a variety of shapes, colors and strengths. Illegally, it is most commonly sold as a white, 2 milligram tablet, colloquially called a bar.

The drug’s quick onset time and short half life, meant to combat panic attacks, distinguish it from other similar medications whose effects are more subtle and drawn out.

“Why it has high potential for problems of overuse, misuse, addiction, that kind of thing, is because it has a fast onset,” Upton said. “So it hits a person quickly and they’ll feel it right away; they’ll get relief right away.

“Benzodiazepines hit the same receptor as alcohol does so for people for whom alcohol provides relief and they really like it, they may also like benzodiazepines, specifically Xanax.”

Junior Megan Cohen, a pseudonym, also struggled with Xanax after she began to use the drug recreationally in summer 2017.

Early in the spring 2018 semester, her addiction put her so behind on schoolwork she was forced to withdraw from three of her five classes. While visiting home for the holidays, her parents asked her if she was hooked on heroin.

She resolved to quit at the beginning of April after realizing she could barely remember any of the past four or five months, she said.

During her near three years at UVM, she has watched the drug’s popularity rise, Cohen said.

“I think it’s kind of an epidemic at UVM,” she said. “I would say it’s kind of like the ‘college heroin’ because I think kids start doing it and they don’t take it seriously and then they get addicted to it.”

A lack of education played a role in Smith’s initial attitude toward trying Xanax, he said.

Before coming to UVM, he went to a small prep school in Rhode Island. He dipped tobacco and occasionally got together with his buddies to drink or smoke weed but that was the extent of his drug experience, he said.

Before he discovered Xanax, Smith, who had always felt socially anxious, spent most Friday and Saturday nights of his first college semester combining alcohol and cocaine until he blacked out, he said.

Around Thanksgiving break, he “snapped” and texted everyone he knew to get his hands on whatever drugs he could, he said.

“I don’t know why really, I just kind of like snapped a little bit,” Smith said. “I hated being sober and like just the sort of social thing.

“I felt like I was under a lot of stress from my parents … I was kind of spinning it in that way,” Snith said.

He got his hands on a 2 milligram bar of Xanax and intended to take a quarter of it before a party. On a whim, he decided to take the whole thing at the last minute.

For most people such a dose could knock them unconscious, but it left Smith wanting more, he said.

“I get to school and it is all easily accessible and I kind of fell in love with like not being sober,” he said. “And Xanax is like the easiest way for me to not be sober and still do the things I have to do.”

Over the weeks leading up to winter break, Smith began to use Xanax more regularly, often alone and on weekdays.

Often he went through as many as five pills in a single day, he said.

During this period, Smith often experienced inconsistencies in the highs pills gave him, leading him to believe they were fakes made by dealers using pill presses to cut costs, he said.

“You have no idea what they’re pressing it with because you’re not getting prescription Xanax on the streets,” Smith said.

Like Smith, Cohen had initially felt comfortable with Xanax because she believed she was taking a prescribed pill, she said. As she became more familiar with the drug, she realized this was almost never the case.

“The Xanax going around is not real Xanax, there could really be anything in it,” she said. “When I started thinking about it like that, it kind of changed my perspective.

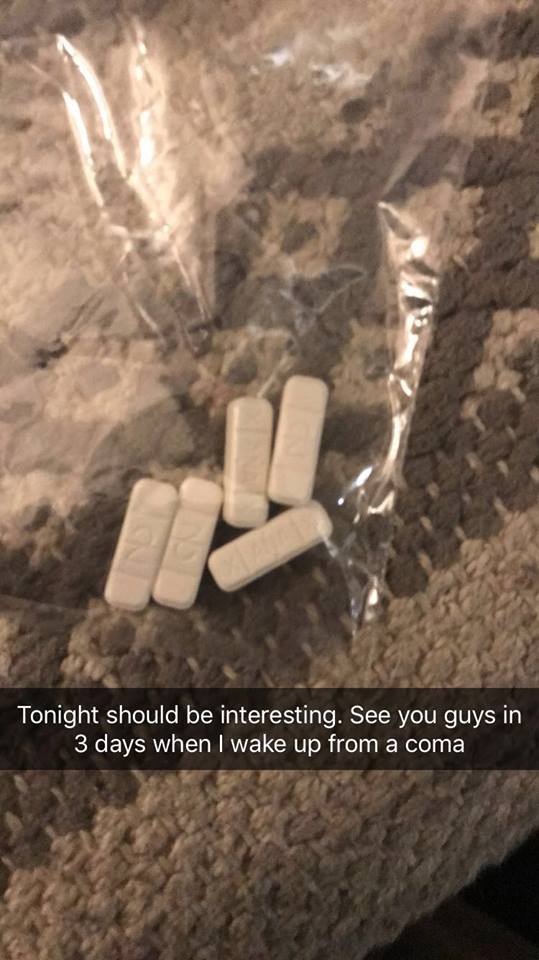

In her apartment, Cohen’s roommate pulled out a small baggie containing 2 1/2 white bars, which she believed to be fake.

“I thought Xanax, like what we were taking, was prescribed,” she said. “But its not prescribed nearly in that high of dosage.”

2 1/2 bars of Xanax sit on junior Megan Cohen’s coffee table. Cohen, a pseudonym, believes most Xanax bars available on the streets are imposters.

Soon after dropping the pills on the table, Cohen asked her roommate to put them away and encouraged her to flush them down the toilet.

“I think it’s very similar, prescription painkillers and Xanax, because it’s not even real Xanax,” Cohen said. “Prescription pills are kind of a gateway to heroin and I feel like so is this Xanax.”

To a psychologist like Upton, it would be unfair for recreational users to assume the pills were safe even if they came straight from the pharmacy.

“There’s an assumption that if something can be prescribed by a doctor it’s going to be safe,” he said. “Each individual situation deserves an individual assessment by a skilled person.

“Trying to generalize general information to your specific situation without a complete assessment has its own risks.”

Over the break, Smith had no access to any sort of drugs and felt some minor withdrawal symptoms, he said.

Smith’s mom, who had always carefully disposed of excess prescriptions around the house, confronted Smith about his drug use after his brother expressed concern to her following their day on the slopes, he said.

Since then, Smith has made an effort to stay of Xanax but at times finds it impossible to resist.

In one instance, he tried to get a friend some weed from his old Xanax dealer and was offered some bars while he was there.

“It was like, I got $40 in my pocket, what am I supposed to do? You know?” he said. “So I would just get eight bars and go through them between Monday and Tuesday.”

Smith still uses other drugs, like MDMA and LSD, but stays away from downers in part due to his fondness for them, but also because he feels there is no upside to their use, he said.

“I’m not opposed to anyone saying I want to try this drug,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of drugs out there that you should try, but like there’s no point to Xanax, there’s no other perspective – it’s just black out.”

For some students, especially those who may be stressed about school or their uncertain future, Fontana believes that very numbness may be the appeal of Xanax, he said.

Particularly, he has noticed a popularity amongst people like Smith, students from suburban backgrounds who have always been praised for their academics and athletics, whose identities are uprooted in the university setting, he said.

He has also noticed that the drug seems to be less popular for the female students he has spoken to than the males, he said.

One possibility for this discrepancy, as one student pointed out to him, is the heightened danger women face when blacked out, he said.

For Cohen, such dangers were frequent reality, she said.

“I think it’s possible to get into situations without realizing it, it’s kind of inevitable,” she said. “When you go out and blackout at a bar anything could happen.

“You could go home with anyone and wake up somewhere and you have no idea – it’s happened, yes.”

Junior Megan Cohen, a pseudonym, holds a pair of fake 2 milligram Xanax bars. Cohen regularly used Xanax recreationally over the course of several months.

Despite a few theories, Fontana is still trying to connect the dots to explain the recent Xanax trend, he said. He tends to believe the issue stems from some sort of crisis students are facing combined with a lack of education about the drug.

“It almost always starts socially, and when you start doing it by yourself you still wanna think ‘no I’m not self medicating’ because then have to think ‘I must be medicating something,’” Fontana said. “We don’t often wanna look at that for ourselves.”

Jamie • May 1, 2018 at 8:12 am

While I understand the message you’re trying to send, I feel like this entire article completely ostracizes those who are prescribed xanax for anxiety disorders and panic attacks- and take it as prescribed. Any prescription medication can be abused, but there are also people out there who don’t abuse it and need these medications to function. Are benzodiazepines addictive? Yes. But when taken under a doctor’s control there is a very low risk of addiction. Don’t shame everyone who takes xanax or other benzodiazepines for legitimate psychiatric disorders just because there is a handful of people out there taking them for the wrong reasons.