After the Kake Walk: A history of UVM’s racial climate from Lattie Coor’s presidency to the present

March 2, 2016

Student activism was common at UVM throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, resulting in the creation of some of the first African-American, Chicano/a and women’s studies departments in the U.S., English professor Nancy Welch said.

“At UVM, these actions — and the establishment of courses in women’s and U.S. ethnic studies — were delayed by 20 years, perhaps because the racist tradition of Kake Walk had to be dealt with first,” Welch said.

The First Waterman Takeover

Lattie Coor said he was 39 years old when he took the office of UVM president in 1976.

“It was pretty unusual, but I think that is the average age [for university presidents] now,” Coor said in an Aug. 4 interview. “Back then it was more normal to be in your 50s. I was glad they were willing to invite me to the position.”

Coor was president through the 1980s, while Sen. Bernie Sanders was mayor of Burlington, he said.

This included April 1988, the first time students occupied the Waterman building, according to a history of diversity on the UVM website.

Karl Jagbandhansingh ‘05 said in an April 23, 2011 video reflecting on the 1991 “Waterman Takeover” that he was a part of the group of students who occupied Waterman in 1988.

“So I had heard about racism, my dad had told me stories but I never had felt the impact of what that meant,” Jagbandhansingh said in the 2011 video. “So having a chance to be here and see the devil up close and the act of getting beat up for no reason except that I was different really woke me up.

“In the beginning you take it kind of personally: What did I do wrong? How what could I have avoided this situation?” he said. “Luckily, there was a group of us who started talking and we realized it wasn’t an isolated incident.”

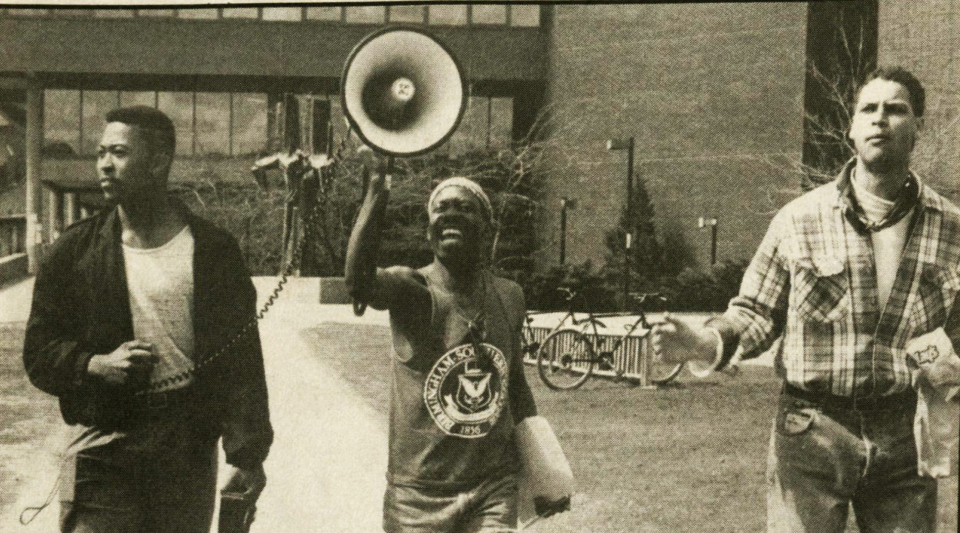

Minority students stand in the Waterman building which they have been occupying for three days.

The 1988 Waterman Takeover happened because minority students were frustrated with the lack of cultural diversity on campus, according to a history of diversity published on the University’s website.

“There had been very little activity in adding courses and programs that represented the richness and diversity of subject matter embraced in the minority experience,” Coor said in an April 1988 statement.

Professor Emeritus James Loewen said a decision had been made two years prior to the takeover to drop a diversity course. Loewen called the move “institutionally racist” to the “surprised, blank stares” of his fellow faculty members, he said.

The takeover began April 18, 1988, and ended five days later on April 23. The students who occupied the building also went on a hunger strike, Jagbandhansingh said in the video.

During the five days of occupation, Coor met with students every day to negotiate their demands, according to an April 28, 1988 Cynic article.

On April 22, Coor said they had reached a “deadlock” in their talks and called in mediation, according to the article.

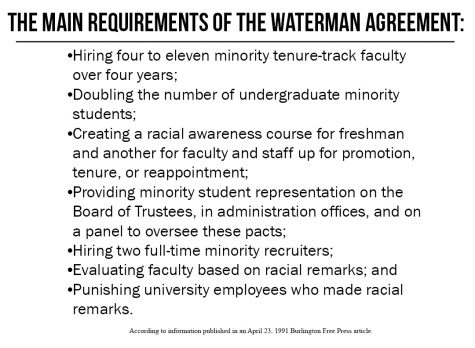

The next day, with mediators present, Coor signed off on the students’ list of demands regarding diversity at UVM, called the Waterman Agreement.

The board of trustees brought up the issue at their May 1988 meeting, according to an April 28, 1991 Cynic article. The board unanimously approved a plan to combat racism at the University, according to a summary of the event by UVM.

This first takeover resulted in the one-credit race and culture diversity course requirement that was mandatory from 1989 until 2005, and funded by a grant that expired in 2005.

In 2006, the faculty senate voted to implement a new six-credit diversity requirement, which went into effect in the fall of 2008, according to the University’s diversity timeline.

Not long after the 1988 takeover, Coor said he resigned and announced he’d be moving to Arizona State University.

No job should last forever, Coor said.

“[University presidents] should understand what they and the institution are trying to accomplish and then step down and let new leadership come in,” he said. “I love UVM – my daughter has just joined the faculty, I visit often.”

So far, Coor was the longest serving president at UVM, according to UVM’s history of its presidents.

“I’m a great believer in cycles and institutional cycles,” Coor said in the August interview. “Fourteen years, then and now, was a relatively long period of time.”

The Second Takeover

Jagbandhansingh said he was also one of the 22 students who occupied Waterman for a second time in 1991 — this time for 20 days.

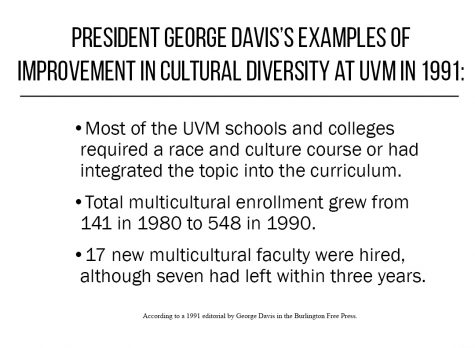

Coor had resigned at this point, and was succeeded by George Davis, according to UVM’s history of the presidents.

“The [administration] said okay, the new president is going to sign the document to affirm his intention to uphold the meaning [and] spirit of this document and then he refused to do that,” Jagbandhansingh said. “Then we got upset…You are not going to even say the words? Come on, you’re gonna drag your feet but you aren’t even sign this document that we worked hard to get?”

Until the spring semester of 1991, Davis had pledged he would sign the Waterman Agreement that had been drawn up by Coor and minority students during the 1988 Waterman Takeover, according to a history of the event.

However, at the start of the next semester, Davis changed his mind.

“I came to the conclusion that I was not prepared to sign the agreement because I felt I would not be able to deliver on the promises made,” Davis said.

At that point, 5.8 percent of students and 5.2 percent of faculty members were of a minority, according to data reported in a May 1991 edition of The Vermont Times.

The only other public higher education institution with lower levels of representation in New England was the University of New Hampshire, according to the data.

In December of 1990, Maude Lightburn, an African-American professor at UVM, was fired, according to a January 1991 Cynic article. Lightburn filed charges of racial discrimination against UVM, according to the article.

“It wasn’t just a bunch of crazy students of color,” Jagbandhansingh said. “The way [the protest over Lightburn’s firing] was able to happen was that there were a lot of white supporters who also cared. We want a good education. This is important for us. It’s important for the world, so then we had the takeover in 1991.”

Meghan O’Rourke ‘04 was a student at the time, and said while only 22 students occupied the second floor of the Waterman building, the rest of the building was occupied daily by hundreds of students who were teaching about diversity at UVM.

O’Rourke said that while helping with a video project after the takeover, she remembered students being interviewed and saying they had learned more about racism in those two weeks than their entire time at the University.

Mike Griefendorf ‘90, who graduated a year before, was working as a cook at the Radisson Hotel in Burlington at the time, and said he knew many students on campus.

“I was just a privileged white kid myself,” Griefendorf said, “but because they were my friends, I joined the movement and so did a lot of other white kids.”

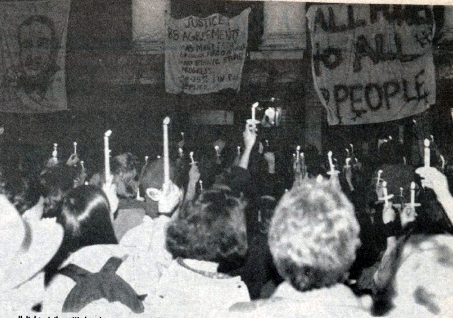

Protests during the 1991 Waterman Takeover.

A lot of the student activism that ignited the second Waterman takeover was a reaction to actual hate crimes and rape on campus, he said.

“The Asian and black students felt harassed at the time,” Griefendorf said.

The Black Student Union did not participate as much in this takeover compared the one in 1988, he said.

“They were more well off and didn’t want to screw up the opportunity of their education,” Griefendorf said.

“The event attracted all kinds of races of people,” he said. “Gay men would complain that they weren’t getting enough attention, Native Americans from the state of Vermont felt unrepresented and the Irish community of Vermont started to call us out because the Irish were shit on when they first came to the state of Vermont.”

During the first two days of the protest, Davis climbed a ladder to the second floor balcony to meet with the students occupying his own office, according to a Cynic article.

President George Davis climbs a ladder to get into his own office in order to negotiate with the student protesters occupying the building.

“We have a lot of work to do. Many, if not all, of their concerns are valid,” Davis said in an April 24, 1991 Burlington Free Press article.

After the third day of the takeover, Davis said in an interview that his recent actions had not helped his relations with minority students at the school.

“For me, as a white Vermont student who had grown up with very little contact with people of color outside of my media diet on the ‘70s and ‘80s, my eyes were open to the personal racism that people experienced, both outright hate-racism and sort of side-eyed racism and the institutional racism that people were experiencing with the University,” O’Rourke said.

The institutional racism she referred to included using affirmative action to recruit students of color from mostly white prep schools, she said.

“That was the kind of institutional stuff that was going on and was challenged by the students,” O’Rourke said. “So in that environment, and having my eyes opened I understood that, ‘Fuck you, whitey!’ was talking to history, not to skin color and not to the individual.”

Griefendorf said the “real power hub” in the University at that time was the board of trustees.

“People started protesting them and that got under their skin so they would start to move meetings around,” he said. “So that was very effective, to go right to the decision makers.”

According to a board of trustees resolution that was unanimously adopted May 4, 1991, the board stated their “firm support” of Davis’ decision not to negotiate demands with anyone “unauthorized” to occupying the University’s property.

The board further stated the University “will not develop policies, procedures and programs in an atmosphere of coercion and duress,” according to the 1991 resolution.

After 20 days of occupation, on May 12, 1991, approximately 90 state police officers pulled up outside of the Waterman building, put eight students still occupying Waterman into a bus and took them away, Griefendorf said.

“I don’t think anyone knew what day, people probably assumed that at some point arrests would happen,” O’Rourke said, “but I don’t think people knew it was going to happen at that time or in that manner,”

Most of the original 22 students who had occupied the building left once a police order had been issued, but eight students and a faculty member stayed behind, according to videos of the arrests from the Center for Media and Democracy.

“While I saw one of my friends being arrested, there was another guy petting his head [as a comforting gesture] which still really is emotional to think about for me today,” Griefendorf said.

O’Rourke was protesting outside Waterman while the arrests were taking place, she said.

When the bus filled with the arrested students was about to leave, community members and students sat in front of it, she said, in an attempt to support their friends who had put their University careers on the line.

The majority of those who tried to stop the bus were also arrested, O’Rourke said.

“That feeling as if you’re part of something that is pushing forward a conversation, that you’re finally being heard by a campus, by a community, that you’re finally being possibly heard of people in a position of power, and then to realized how powerless you really are is very emotional,” she said.

Howard Dean, the lieutenant governor of Vermont at the time, sent a letter to Davis after the arrests praising him on handling the situation “in the most outstanding, humane way possible,” according to the letter.

As for getting arrested for his actions in the 1991 Waterman Takeover, Jagbandhansingh said in the 2011 video, “It is what it is.”

Aftermath of the Waterman Takeovers

At one point, Davis walked out into the hall and said to the protesters, “You are disrupting the flow of business in this wing,” according to the magazine.

All seven protesters were arrested by Burlington Police Department officers, according to the issue.

Before arresting them, the police officers warned the students they would be forcibly removed, to which Jagbandhansingh said he and the other students were not creating a disturbance and would leave peacefully as soon as the police officers explained why the two student protesters had been dismissed from the University, according to the 1991 issue.

David Jamieson ‘92 was one of the African-American students who participated in both takeovers, Megan O’Rourke ‘04 said.

Jamieson had been a leader in the first Waterman takeover and was one of the founders of the original Black Student Union at UVM, according to UVM’s history of diversity. He died of AIDS in 1992, leaving a collection of artwork that is privately curated in Washington, D.C., according to his collection’s webpage.

“David Jamieson was a beautiful man who was at the University for a long time, had one of the deepest hearts and spirits that I knew,” O’Rourke said. “He spent a long time just painting outside the takeover, and that was his support.”

In the Davis Center, on the wall opposite to the stairs leading up to the fourth floor, a piece of Jamieson’s art is on display. Beneath the art is his signature and story.

“I don’t think we did very much because we were only there for four years and we were out of there,” Griefendorf said.

This is a common problem with student activism because after four years, everybody who is involved in the process of whatever was being worked on is gone, he said.

“It’s very challenging to pass the torch from one generation to the next in four-year terms,” Griefendorf said.

In 2011, on the 20th anniversary of the 1991 Waterman Takeover, alumni who participated in the occupation, along with current and past faculty and staff at UVM, got together to reflect on the event and what has changed at UVM since then, according to the April 23, 2011 video from CCTV.

T.J. Whittaker ‘91 was at UVM for both of the Waterman occupations, he said at the April 23, 2011 event.

The 1988 Waterman Takeover “awakened” him and led him to become more involved in the Black Student Union in 1990 and 1991, Whittaker said.

“We had kind of come into our own then as activists, and the rest is history,” Whittaker said.

Pat Brown, now the director of Student Life , talked about his role as a University employee during the time of the second Waterman takeover in the video reflections.

“Sometimes I’m not quite sure what role I played,” Brown said. “Trying to work with students, trying to work with staff, trying to work with faculty. There were people who worked in this building who were very scared because they didn’t know things.”

Jagbandhansingh said in a 2006 interview with Matrix Magazine the problem was the “unresponsive” administration.

“When we would talk with them, [the University] would agree with all the stuff we were saying, would agree that racism was bad, would agree that there needed to be racism awareness classes,” he said, “but when push came to shove they would always drop our stuff because it cost them money.”

The experience was “eye-opening” for the students involved, Jagbandhansingh said.

“A lot of us were really naive in thinking, ‘Okay this is an institution that’s supposed to be about higher education’ and really it’s a big business,” he said in the interview. “And we were lucky enough to be able to go back in history and look for a solution to our dilemma.”

Race at UVM was a “tortuous issue,” Coor said in a Sept. 15, 1991 Burlington Free Press article about him receiving a honorary doctor of laws during UVM’s bicentennial convocations in 1991.

“Vermont is the whitest state in the nation… [and that] is a complicating factor at UVM,” Coor said in the 1991 article. “I continue to believe that’s the largest single barrier to diversity here. There isn’t a natural environment because minority populations haven’t been here historically.”

Diversity University

I would say it was a charged learning environment; a charged, energized, learning environment,” O’Rourke said. “It was also very stressful and emotional.”

After the 1991, shacks and shanties were on the Waterman Green, and stayed there until December 1991. Protesters dubbed this makeshift community “Diversity University” used it to continue the two-week diversity curriculum that had been taught in the classrooms of Waterman during the takeover, according to the history of diversity at UVM.

“[Diversity University] has no president and no peons: it has as many teachers as students, as many bodies as heads,” the organization’s statement of purpose read. “We are not here just to educate ourselves.”

Davis resigned in October 1991 after the board of trustees rejected his proposal to fix the University’s budget, which included getting rid of the engineering department, according to the University’s history of its presidents. The board named Thomas Salmon as interim president two weeks after Davis resigned.

Salmon had previously served as governor of Vermont from 1973 to 1977, according to his bio on UVM’s website. He is currently associated with the Salmon and Nostrand law firm in Bellow Falls, Vermont, according to their website.

He was unable to be reached for comment.

In December 1991, an individual set fire to the shacks and shanties, according to an article in The Vermont Collegian from that month. It had been a rainy Friday and no individuals were present during the arson and no one was harmed, according to the article.

The perpetrator’s identity was never discovered, though in an anonymous recorded message sent to the Vermont Collegian, a male claiming to be a UVM student, said he started the fire because the “campus is ugly enough without having this shack out on the green,” and because he believed Salmon was “going to get things done,” according to the article.

“I handed [Salmon]… a very safe and fast way for him to get rid of the shacks and for him to come down on the policies as they are going to be from now on,” the anonymous male said, according to the article.

After the fire, the Diversity University leaders rejected the administration’s offer of a permanent office in one of the school’s buildings, according to the article.

The administration then announced it would not allow Diversity University to be rebuilt.

No arrests were made regarding the arson.

The mid-90s Hunger Strikes

Many who were not in the Waterman Building during the 1991 takeover showed their support through a hunger strike, refusing to eat anything until the administration and the student protesters came to an agreement, Griefendorf said.

In December of 1995, Shontae Praileau ‘96, began another hunger strike in protest of the lack of cultural diversity at the University.

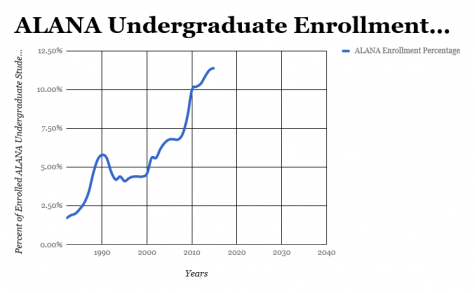

About 4.1 percent of undergraduate students enrolled at UVM were multicultural, according to a report by the Office of University Research.

In 1995, three women of color received death threats in their respective residence halls, which was one of the factors that led to Praileau’s decision to go on a hunger strike, according to a Jan. 25, 1996 Cynic article.

One of Praileau’s demands was that the ALANA students be able to choose the director of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, and the current director be fired.

It took 35 days before Salmon or anyone else in the administration responded to her protest, according to the article.

In the 56th day of the hunger strike her demands had still not been met, according to the article.

“Telling me they refuse my demands won’t work for me either,” Praileau said in the 1996 article. “I did not start this for them and I will not end it for them. This does not revolve around you. There are bigger issues at UVM.”

Praileau’s hunger strike lasted a total of 64 days, at which point Kei Kurihara ‘96 “picked up the torch,” according to the Cynic article.

Praileau declined to comment, saying she never did it to be in the spotlight and the hunger strike was never about her. She said commenting 21 years later would only negate that.

Kurihara was unable to be reached for comment.

Diversity Growth in Enrollment

From 1995 to 2014, the overall undergraduate population at UVM has grown by roughly 75 percent, with an increase of about 2,400 undergraduates, according to the UVM Sourcebook.

Despite this, the “multicultural” population at UVM has not increased beyond 25 percent of the undergraduate population, according to the headcount of multicultural students at UVM from 1995 to 2014.

In 2014, 425 undergraduate students identified as Hispanic/Latino, 240 as Asian, 104 as Black/African-American, 20 as Native American and two as Pacific-Islanders, according to information from the Office of Institutional Research. In addition, there were 273 students who identified as two or more races.

There were 7,978 white students, according to the sourcebook.

Wanda Heading-Grant ‘87, vice president of human resources, diversity and multicultural affairs, also spoke at the 20th anniversary of the 1991 Waterman Takeover in 2011.

Heading-Grant was first made an administrator in 1991 when she became the assistant director of affirmative action at UVM, where she would handle grievances and complaints regarding racism, according to the October 1991 issue of the Vermont Collegian.

She has not yet responded to request for comment, but in the 2011 video said UVM has a long history with diversity.

“We currently have a lot of work to do, I have said that over and over again,” Heading-Grant said in the video. “But with strong leadership, we can do it. We can advance diversity here. We will move far away from the painful past and closer to an institution that embodies its mission and all that it means to be an institution that embraces multiculturalism.”

This article is published exclusively online and is an addition to the Cynic’s three-part series examining the past, present and future of the University of Vermont’s racial climate.

Reporting by: Sarah Olsen, Bryan O’Keefe, Cole Wangsness, Kelsey Neubauer and Craig Pelsor.

Additional reporting by: Meghan Ingraham and Ryan Thornton.

Videos from CCTV website, filmed by Nat Ayer of CCTV. You can access the full video here

Featured photo taken by Bryan Agran. It was originally published in the April 25, 1991 issue of the Cynic.