‘Freedom and anonymity:’ The social acceptability of Burlington street art

April 14, 2021

It is hard to miss the delightful auras of chaos gracing Burlington rooftops, alleyways and dumpsters, but even harder to cease the flow of controversial expression.

There has long been a distaste for graffiti in the greater Burlington area. The increased tagging seen around Burlington over the last year has only perpetuated the criminality of this unique art form, yet a crucial perspective is missing from the narrative.

The recent Seven Days article, “Burlington Grapples with Pandemic-Era Graffiti,” discusses how graffiti negatively impacts the aesthetics of downtown Burlington.

The article reports on the recent uptick in graffiti vandalism in Burlington and attributes such an increase to environmental, political and social factors, including a categorization of graffiti as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Downtown Burlington store owners expressed their contempt for this insurgence, and without a Burlington graffiti artist willing to share their position with Seven Days, a crucial perspective in this discourse is lost.

Perhaps it is an issue of ignorance or confusion; business owners and city officials believe graffiti threatens the fashioned pristinity of Burlington, but graffiti artists just want to practice their craft, to be seen in a society that overlooks them.

It is a very nuanced debate, and one that should be explored rather than painted over.

Graffiti does not always adhere to the socially acceptable forms of creative expression, and thus is seen by many as degenerate. But it is much more than scribbles on the wall.

Ms. You, a local graffiti artist, uses their work as an emotional outlet, just like any other artist would.

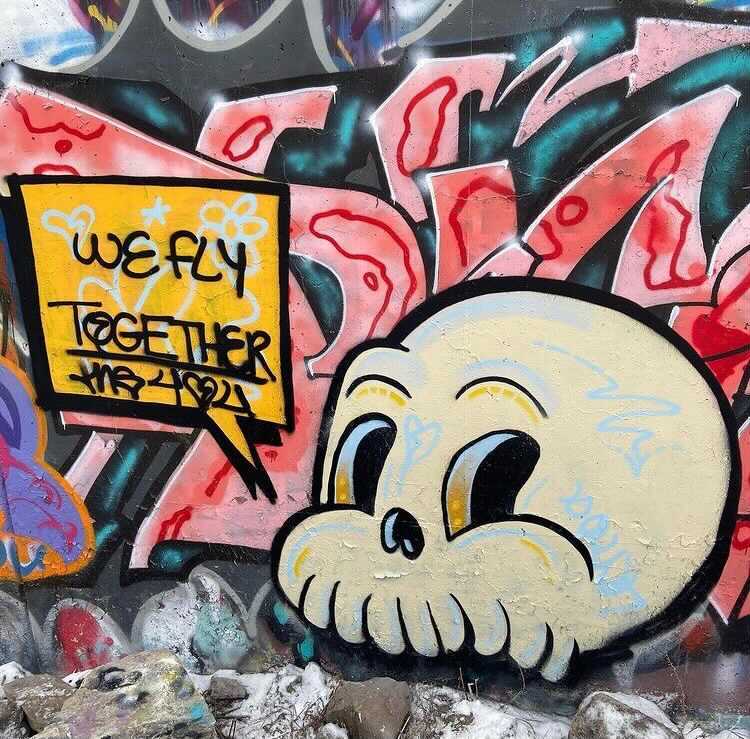

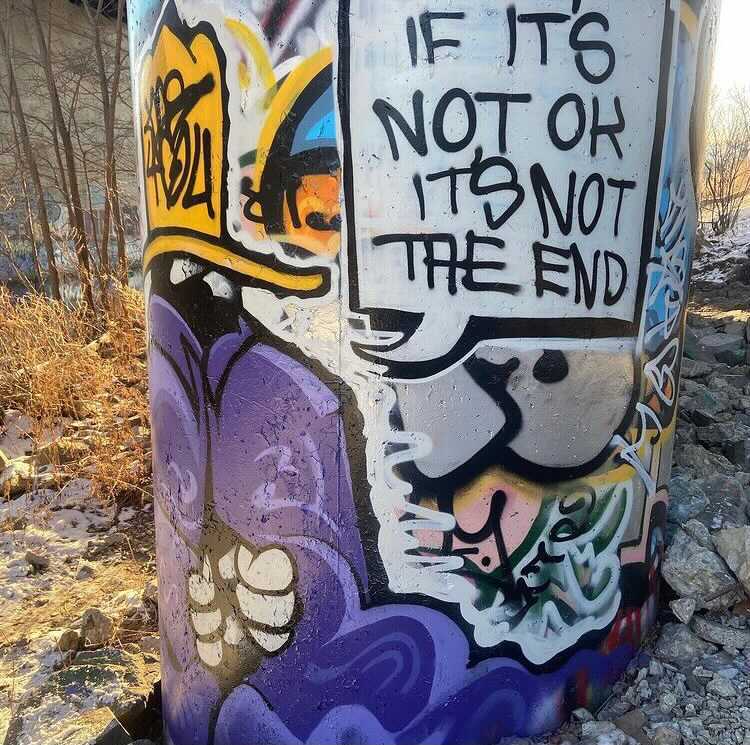

“I started [graffiti] again to help process a lot of deaths in my life, deaths of my friends,” Ms. You said. “I started doing pieces around town and writing little notes on things that I would have wanted my dead friends to see, and that would have made them smile.”

As the outliers in the arts community, they have found places they can turn into their own. Whether it be downtown tagging rooftops or hidden graffiti spots off foot trails, the graffiti community has made space for themselves.

“There’s the younger generation who are super aggressive, putting their pieces up where everyone can see them,” Ms. You said. “Then the older generation goes to the spots where only graffiti writers go, and if people stumble upon them, it’s because they’re walking down a random trail.”

Although there are legal graffiti spots in Chittenden County, graffiti artists are pushed into the rundown peripheries of the city. Not only is there less fear of having the police called, but peripheries tend to be utopias free from judgment.

One of those spots is the infamous Moran Plant on the shores of Lake Champlain.

Over the last year, the Moran Plant was deconstructed to just its steel frame as a part of the city’s plan to reinvigorate the Burlington lakefront, and because of obvious environmental and public health concerns.

Before its demise, the Moran Plant’s plain brick facade was decorated with all different types of graffiti and tags. During the deconstruction, the murals and paintings inside the building were briefly put on display before being reduced to a pile of brick.

“The artwork inside and outside of the building was amazing,” Ms. You said. “But you could’ve stepped on the floor and it would have crumbled beneath your feet. Anyone going in there was risking serious injury.”

Abandoned buildings in ruin typically attract graffiti artists because there is not the fear of being caught or having the police called.

Anthropology Professor Scott Van Keuren has long been fascinated with ruins and graffiti, especially in the derelict urban areas that have been abandoned by mainstream society.

“Graffiti artists were drawn to the Moran Plant because it’s about the freedom and anonymity of the space,” Van Keuren said. “It was a safe place, and abandoned areas are places where you can illicitly sneak in. When the ownership is ambiguous, you can make that your palette.”

As a home to an underground community of graffiti artists, the deconstruction of the Moran Plant reflects the power relations between the underground community and those in power.

“There were a lot of memories there. The new project stripped all those memories away and all of the evidence of the underground engagement,” Van Keuren said. “I don’t think much of Burlington really cares about that, but it mattered to a number of people.”

Art is about breaking and bending the rules. If no limits were pushed, there would be no artistic development. There would be no Picasso, no Basquiat, no Warhol, no Kahlo and no Pollock.

Art is about walking that fine line between what is socially acceptable enough for people to be intrigued, but socially unacceptable enough that it creates a controversial, unconventional dialogue. This is what prompts artistic development.

“Graffiti is a very selfish thing for me to be doing, but artwork helps me heal. I like putting tags up to help heal other people,” Ms. You said.

The emotional release and communal experience of street art makes it an unstoppable force.

“People are still going to want that adrenaline rush and go out and tag a building that is owned by a giant company. That problem is never going to necessarily go away,” Ms. You said.

Looking at past civilizations can also help configure the motivations behind graffiti and tagging. It shows that graffiti is not just a sign of the times, rather a shared cultural experience across temporal and geographic ranges.

“People just signing their names is a big pattern that goes all the way back to antiquity. People have been doing that for thousands of years, and maybe it’s a hand stencil, but it is a mark of their identity,” Van Keuren said.

There is no doubt modern graffiti in Burlington and other cities across the world tells a story larger than what it seems at face value.

“If a future archaeologist was to look at the graffiti we are seeing now, they would know that this was a strange year full of upheaval,” Van Keuren said. “They may not know what was going on, but the surge in graffiti activity would reflect the political and social climate.”

The word graffiti was first used to describe the inscriptions found in the Italian city turned archaeological site, Pompeii. It is derived from the Italian word ‘graffio,’ or ‘a scratch’.

However, there is a double standard between what types of graffiti are appreciated.

“If something is thousands of years old, it’s seen in a totally different light than it is from Saturday night and shows up on the side of a building,” Van Keuren said.

We admittedly geek over ancient graffiti from Ancient Rome or Saqqara because it is a remnant of ancient counterculture that provides insights into their society.

Yet, graffiti is one of the first demonstrations of the basic need for human expression, one that has given way to artistic development.

Embracing graffiti art is the first step in controlling the rampant and random tags. Creating spaces for graffiti artists to do their craft in public instead of being pushed to the abandoned, decrepit corners will allow for this art form to flourish.

Yes, part of graffiti is the appeal of danger and risk, but greater acceptance of this art form could create a new facet of the Burlington arts community. When it becomes socially acceptable, there is more room for refinement, for mastering of their craft.

Graffiti artists will no longer fear the repercussions of their self expression.

Burlington prides itself on being an inclusive city dedicated to the arts, and ingratiating graffiti artists into this community could diversify and enhance the rich dynamics of how Burlingtoners view and consume art.

First, there has to be an understanding that graffiti art is not the corrupting demon it has been thought out to be.

“We have a typical outsider view of something we don’t understand, and can’t really appreciate. It’s not a part of our experience, so it’s a complicated thing, but there’s a big place for it,” Van Keuren said.