Kake Walk: Alumni, faculty and students reflect on 73-year tradition

February 24, 2016

For 73 years, UVM fraternity members danced in blackface and satin tuxedos during the longest running winter carnival in the country.

At its peak in the 1960s, this event, known as the Kake Walk, was held twice over a February weekend in the Patrick Gym in order to fit all 8,000 spectators, according to ticket sales reports.

The concept of the Kake Walk originated with slaves on northern plantations who performed in outrageous ways for their owners. The “most comical” slave won a piece of cake, sociologist James Loewen stated in the book “The University of Vermont: The First 200 Years.”

Kake Walk began in 1893 to replace a canceled military ball at a time when Jim Crow laws were rampant and minstrel shows were becoming more popular in Vermont, Loewen wrote.

In the years following the Kake Walk’s end, it wasn’t talked about, Ken McGuckin, who walked in 1965, said.

“It was blacklisted – you couldn’t say the words on campus,” McGuckin said.

Current SGA president Jason Maulucci said some students aren’t aware the Kake Walk existed, or that it was an institutional part of UVM.

“It’s so important that we are reminded of what our past was, so that we know that we should never repeat that past,” Maulucci said.

A Family Tradition

I remember my father used to take us on Sunday afternoon,” John Maley ‘65 said. “We’d go ‘Let’s go for a ride Daddy,’ when there were eight kids in the family, we’d all pile in the car and we’d look at all the snow sculptures and we’d decide which one was the best.”

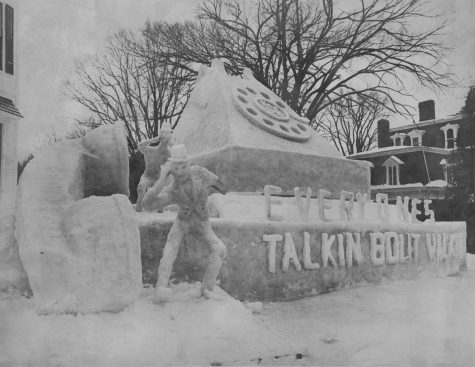

One of the snow sculptures during the Kake Walk snow sculpture contests.

These sculptures were part of a larger, annual campus-wide Winter Carnival, which included fraternity skits, the Kake Walk and musical performances throughout the weekend.

John Maley said his family was more involved in the Kake Walk than just judging the ice sculptures; both his parents, Donald Maley ‘41 and Rita Maley ‘39, were involved in Greek life during their time at UVM and the Kake Walk.

Snow sculpture built for the Kake Walk’s fraternity ice sculpture contest.

When Donald Maley was a senior in 1941, he served as chairman of the Kake Walk program committee, according to a Feb 21, 1941 Cynic article.

“I knew about the Kake Walk since I was a little kid…my parents were a part of it,” John Maley said.

When John Maley came to UVM he pledged Delta Psi, he said.

He attended UVM during the “genesis” of the civil rights movement, something he said deeply affected the student body’s view of the Kake Walk.

“Watching TV there were hoses, mowing these civil rights people down,” he said, “and we thought, holy shit we gotta start thinking about all this.”

One of John Maley’s fraternity brothers, African American student Bob Nurse ‘64, gave a “fairly impassioned,” speech about how the Kake Walk impacted his black peers, he said.

Nurse told them that while the Kake Walk didn’t upset him because he understood the excitement as a UVM student, his black friends at home couldn’t believe it was happening.

An Overwhelmed Minority

One of the first records of any objection to the Kake Walk came from Constance Motley, who at the time was working under Thurgood Marshall as a member of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, according to her Sept. 29, 2005 obituary in the New York Times.

In 1950, Motley sent a letter to then-UVM President William Carlson expressing her disapproval of the Kake Walk.

“It is difficult for us to conceive of any group of enlightened Americans in this day and age sponsoring and presenting such shows,” she stated.

Motley was the first black woman to serve in the New York State Senate, and helped pen legal briefs in the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown vs. Board of Education, according to the article

Some of the most commonly held stereotypes of African Americans were formed during minstrel shows, Motley stated.

By the time Kake Walk came to an end, the ratio of white students to black students at UVM was 500 to 1, political science professor Garrison Nelson, judge of the 1969 Kake Walk, said.

“[The University] said, ‘Well, the blacks aren’t complaining,’” Nelson said. “Well there’s only seven [black students], they weren’t going to complain,; they’re already feeling like an overwhelmed minority.

Students were pivotal in ending the Kake Walk, said Wanda Heading-Grant, vice president of Human Resources, Diversity and Multicultural Affairs.

“I am hopeful that the current generation of students, at UVM and at other schools, will play an equally important role in helping create a society that is free of the painful effects of racial discrimination and insensitivity,” Heading-Grant said.

Junior Drew Cooper, who is black, sees a relation between both the Kake Walk and modern American appropriation of black culture.

“Everybody wants to be black, but nobody really wants to be black,” Cooper said.

Junior Addy Campbell, a member of ALANA, said the apparent lack of diversity in Vermont has an effect on the way people see race.

“In a place of overwhelming whiteness, it is very easy for white people to think that we don’t have problems with racism,” Campbell said. “This just isn’t true.”

Dissent in the 1950s

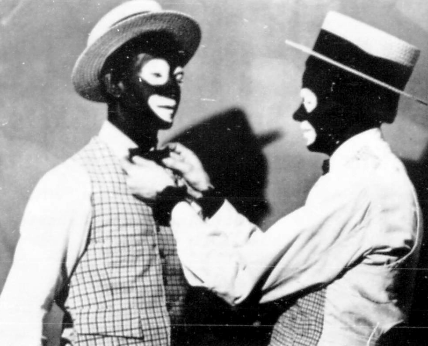

In the 1954 Kake Walk, Phi Sigma Delta “shattered” the long-standing tradition of wearing blackface by donning purple makeup, their fraternity color, according to a Feb. 25, 1954 Cynic article.

The fraternity made the decision to forgo blackface because two of its members, LeRoy Williams, Jr. ‘57 and Richard Dennis ‘57 were black, Williams said.

“Sadly, our fraternity received a considerable uneasy backlash from this momentous decision,” he said.

In 1957, the morning of Friday night’s event, LeRoy Williams took his date, Joyce Austin, to the Rest Haven Motel, where they were denied service “because [they] were negroes,” Williams said.

Following this incident, nearly 400 students met to protest the actions of the hotel employees, according to a March 7, 1957 Cynic article.

The opposition resulted in the creation of the UVM Council on Human Relations, which supported an anti-discrimination bill in Vermont, according to a March 14, 1957 Cynic article.

In 1957, Vermont passed a statute prohibiting private establishments that catered to the general public from discriminating on the basis of race.

Williams said he also received support from the surrounding community.

“I must have received over 50 letters from Vermonters welcoming me and my girlfriend into their homes, should I or my family ever need a place to stay,” he said.

Williams said that despite the implications, he never felt there were any racist overtones from students who wanted to retain blackface at Kake Walk.

It was probably the “hypnotic adherence to tradition” that made it difficult for people to realize how blackface may have impacted minorities on campus, he said.

Williams said he sees a relation between the “tradition” argument for blackface at Kake Walk and current arguments in support of athletic teams with Native American names or symbols.

“Tradition can be the enemy of common sense and progress,” he said.

Joyce Williams, LeRoy’s girlfriend at the time they were denied service at the motel, was his high school sweetheart, and eventually his wife. They were married in 1958, the year after his graduation.

LeRoy and Joyce Williams have four children and 10 grandchildren.

Joyce died in 2013.

Switching to Green Face

Larry Roth ‘66 and Norm Coleman ‘65 represented Alpha Epsilon Pi as partners in the 1965 Kake Walk, and developed a friendship that has lasted over 50 years in the process.

“Whatever we did together, it’s built a foundation,” Roth said.

Walkers would begin training four times a week, as early as nine months prior to the event, Roth said.

Training “was all handed down verbally,” he said.

Participants would return from winter break earlier than other students to work out two to three times a day in cold fraternity houses, Coleman said.

“There was really a lot of pressure,” he said.

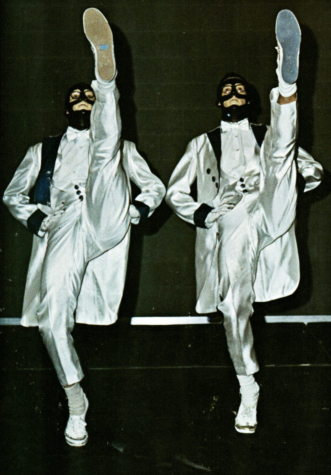

They were expected to dance in synchronization, their hands and feet lining up perfectly with their partner’s, Coleman said.

“We finished each workout [by] running a mile and a half on the track in total unison so we looked like the same person from the side,” Roth said.

While the rest of the school participated in a “four-day, fairly serious party,” Roth said the walkers performed in front of thousands of students, faculty and alumni.

Coleman said there was a certain admiration for the walkers.

“The walkers were held in sort of special regard in that they knew we would do the weekend differently,” Coleman said. “Our job was to bring home the cake.”

Roth said he could recall times even after graduating, when someone would pay for his drink at a bar after a day of skiing simply because he performed in the Kake Walk.

Alumni would flood Burlington every year for the Winter Carnival Kake Walk, Coleman and Roth said.

Another brother of Alpha Epsilon Pi, Warren Kaplan ‘65, said the winter weekend was pivotal to UVM.

“The Kake Walk was an institution at UVM,” Kaplan said. “It was legendary.”

“The day after Kake Walk, the hotels would fill up for the next year,” Coleman said.

Larry Miller ‘66, also a brother of Alpha Epsilon Pi , said “it was a big economic event for the whole Burlington.”

Miller played in the band at the Kake Walk in 1963 and 1964, he said.

There was a lot of pressure on the musicians, as they had to play the event’s signature song, “Cotton Babes,” perfectly for each pair of walkers, Miller said.

“Cotton Babes” became a symbol of Kake Walk weekend, as stated in a Feb. 21, 1930 Cynic article.

“Strains of ‘Cotton Babes’ ringing out into the night will remind devotees of the ancient classic that [is the] Kake Walk,” the article stated.

Coleman and Roth walked in 1965, when the University decided to shift to “dark green and gold face,” according to a 1965 UVM announcement.

“I think people realized [wearing blackface] wasn’t a nice thing to do,” Coleman said.

When UVM ended the Kake Walk in 1969, Roth was working on a village water supply project in South Africa for the Peace Corps.

Due to a lack of electricity in the region, Roth needed to book phone calls weeks in advance and take a truck into the capital to make them, he said.

“Norm got married and I couldn’t go,” he said, “and I had to book a time to call him and congratulate him.”

One day he received a letter that simply read “It’s over,” he said.

“I was very upset,” he said, “but I understood the turmoil and ferment on campus.”

Coleman said he was also saddened by the decision, but now understands the offensive nature of the event.

“It was such a major focal point for all those years,” he said. “I think we all wondered what UVM was going to replace it with… I guess they never quite have.”

Kaplan said he understood it was time for it to end, but was sad the tradition was over.

“Everyone loved it — everyone busted their ass to do this thing,” he said. “You look back and think that it’s such a shame that they got rid of it.”

Coleman and Roth currently serve on the board of directors of the International Cancer Expert Corps, which Coleman described as “Peace Corps for people later in life.”

The organization’s goal is to aid cancer patients in low- and middle-income nations through a network of cancer professionals, according to ICEC’s website.

Student Leader Helps Bring End

Brooks McCabe ‘70 was president of the Student Association, the predecessor to the current SGA, when the Kake Walk committee decided to do away with the tradition.

“The committee understood the importance of the event,” McCabe said. “They also understood the implications of how it was structured and the history.

Neither the University nor the students wanted the event to be offensive to the campus community, he said.

It was a huge decision for both the Student Association and the Kake Walk committee, McCabe said.

He described then-President Lyman Rowell as old school, though not in a negative way.

“He had a hard time appreciating the significance of the issue, but never stood in the way of it,” McCabe said.

Rowell made himself very accessible in order to understand the issue, he said.

Alfred Rollins, Jr., dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the time, was more proactive and better understood the racial implications of the Kake Walk, as well as the need to address the issue in a “dramatic fashion,” McCabe said.

Beyond the campus, the Burlington community had a hard time dealing with the removal of Kake Walk, according to McCabe.

However, Gov. Dean Davis supported the decision to end the event, which helped bring closure to Vermonters, he said.

McCabe named physiology professor Lawrence McCrory as another major player in the Kake Walk’s removal. McCrory was able to communicate with those who either didn’t fully understand why the Kake Walk was ended or who disagreed with the decision entirely, he said.

“He was someone with the stature and the intellect and the ability to present these difficult issues in a way that was more easily understood,” McCabe said.

To further illustrate issues of race at UVM, McCabe wrote a recurring column in The Vermont Cynic called “Whitey Wake Up! To A Racist Vermont.”

“Whitey — do you still think there is no racism in Vermont— much less on campus? Open your eyes! It’s all around you! Ask a few real questions and see how many answers you get,” McCabe wrote in a Feb. 4, 1971 column.

On Feb. 18, 1971, McCabe wrote that “a university can provide a subtle means of perpetuating racism.”

“Racism in America is a white problem,” he stated. “As a white, you are responsible for the racism in your institutions.”

The decision to end Kake Walk was not made in haste, McCabe said.

“It was not something that just happened in the dark of night,” he said. “It was a full and free discussion, and I think at the end of the day, the students, student leadership and directors of Kake Walk … began to see that it was something that needed to be addressed.

The Aftermath of the Kake Walk

Jeffrey Blais ‘71 walked for the Acacia fraternity in the final Kake Walk of 1969.

“I remember going and watching [the Kake Walk] as a freshman and just thinking how marvelous it was,” Blais said.

Blais said he was chosen by his fraternity to train for the 1969 show, though no one knew that it would be the last one at the time.

“It was a very arduous training program for someone who wasn’t in terribly good shape,” he said.

Blais said he doesn’t recall any opposition to the Kake Walk in 1968, but it “became very controversial” during its final year.

The last Kake Walk was accompanied by complaints from minority students, but participants attempted to dismiss opposition by citing the long-standing tradition of the event, he said.

To protest the racist nature of the event, Phi Gamma Delta performed without any makeup at the last Kake Walk, which Blais congratulated them for.

In the aftermath of the 1969 Winter Carnival, Blais said ending the Kake Walk “was a real learning experience for the whole community.”

Two fraternity members in blackface for the 1959 Kake Walk.

People began to question what they were doing, and why, he said.

The black community at UVM was exceptionally small at the time, Blais said, but they were a leading voice protesting the Kake Walk.

“There was a forceful voice that this had to stop,” he said.

In February 1970, Blais served as the assistant treasurer for the new winter weekend, a film and music festival that would replace the Winter Carnival. The next year, he served as the treasurer of the event.

Blais said these weekends were “not raging successes like Kake Walk always was.”

While the 1970 film festival did better than expected, it was not financially successful, Blais said.

He said he was grateful the University supported it as an alternative to the Kake Walk, despite losing money on it.

“The Kake Walk was very lucrative,” he said. “It paid for itself.”

Blais said while he was sure the University was concerned about reduced revenue, they were “adamant” that the new winter weekend take place.

“We were not going to revert — we just couldn’t,” he said.

The Final Kake Walk

Professor Garrison Nelson remembers speaking with one student who argued that the walking segment of the Kake Walk, called “Wokin’ fo’ de Kake,” celebrated the athletic ability of blacks, he said.

“I said, ‘Wokin’ fo’ de Kake’ does not celebrate the intellectual achievements of the blacks,” Nelson said.

The vernacular used during Kake Walk was a “textbook example of racism,” James Loewen wrote, as it specifically distinguished between black and white speech by portraying the former as uneducated.

Two walkers dancing in the final 1969 Kake Walk.

Junior Drew Cooper said the Kake Walk drew on inaccurate and harmful stereotypes of black people.

“The Kake Walk is especially insidious in that it’s a caricature of a caricature,” Cooper said. “White people dressed as black people based on stereotypes envisioned by white people.”

John Gennari, current associate professor of English and director of the ALANA U.S. Ethnic Studies Program, said the Kake Walk resulted from Vermont’s history of minstrel shows in the 19th century.

“There’s always been this dynamic of whites looking to black culture for entertainment,” Gennari said.

However, in 1969, it was clear that the Kake Walk “had run its course,” Nelson said.

“Martin Luther King had been murdered,” he said. “Civil rights really had taken a hold.”

The Phi Gamma Delta fraternity, in a letter to the Burlington Free Press Oct. 30, 1969, stated “it [would] enter no walkers in the annual Kake Walking competition.”

“The Brotherhood empathizes with the feelings of the black community,” they wrote. “[The Kake Walk] is a degrading activity not fit for any winter weekend or celebration, particularly at this period in our nation’s history.”

The following day, the would-be directors of the 1970 Kake Walk officially declared it was cancelled that year, according to their statement at an Oct. 31, 1969 press conference.

“In these sensitive times it is possible to interpret this tradition [of the Kake Walk] as being racist in nature and humiliating to the black people of this nation,” the directors said at a press conference.

“No social practices should be permitted to breed intolerance,” President Rowell said.

Following the decision, “the alums went ballistic,” Nelson said.

“The alums were saying, ‘We won’t give you any money, we want Kake Walk,’” he said.

In a letter sent to Rowell Nov. 12, 1969, Leo Spear ‘49 wrote, “If the University proposes to permit the militant minority to direct the path of this University then, in my opinion, an unrestricted gift will be supporting something in which I don’t concur.”

“We concurred in the thinking that it is a general social weekend and the decision of what should take place was appropriately the students’ decision,” Rowell stated in his response to Spear.

One alumnus sent a letter to Walter Bruska, then-vice president of University Development, about the decision to end Kake Walk.

“I think many alumni, particular those who are most active, will feel badly that the unique winter event has been thrown out,” Phil Robinson ‘48 said in a letter to the Alumni Council.

In the Nov. 11, 1969 issue of the Cynic, Brenda Eastman wrote a letter stating her opposition to the decision based on previous Kake Walk poll results.

When asked whether the walking portion should be removed from the weekend, 1,221 students strongly disagreed, while 437 strongly agreed. 947 students strongly disagreed that Kake Walk is a racist activity, while 316 strongly agreed, she said.

The Student Association supported the decision to “put Kake Walk to sudden, unnegotiated death,” Eastman said.

The Kake Walk wasn’t a low-budget event. According to financial records, the final event in 1969 cost the University roughly $36,000. Adjusted for inflation in 2015, that’s about a quarter of a million dollars, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator.

The University even hosted Janis Joplin and Smokey Robinson as the main performers at the final Winter Weekend in 1969. She died in October 1970.

[aesop_image img=”http://www.kakewalk.enterprise.vtcynic.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/janisjoplinEdited.png” credit=”Photo from the 1969 Airel UVM yearbook.” align=”right” lightbox=”off” caption=”Janis Joplin singing at the final Kake Walk in 1969.” captionposition=”center” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Some alumni sent letters to the Vermont Cynic expressing their unhappiness with the decision.

“Congratulations! The super sensitive students of the hallowed halls have succeeded in destroying one of the few things which brought attention to the University of Vermont,” Peter Coleman ‘66 stated.

Janis Joplin singing at the final Kake Walk in 1969.

However, others spoke up in support of the end of the performance. Ken Wibecan wrote a column in the Oct. 25, 1969 Vermont Freeman, which was reprinted in the Nov. 4, 1969 issue of the Cynic.

“White Kake Walk defenders would do well to stop lying to themselves about the origin of their tradition,” Wibecan stated. “It was conceived out of prejudiced, bigoted minds and as such it must be completely destroyed or the sore that has been created will continue to fester.”

Some alumni commended the administration for bringing the event to a close.

“Where human rights and human dignity are concerned there can be no compromise,” Walter Delano ‘50 stated in a Nov. 3, 1969 letter to Rowell.

Over my dead body

The 1970 music and film festival that replaced Kake Walk was met with some opposition.

After Friday night’s judging of sculptures, the Alpha Gamma Rho fraternity carved walkers as an addition to their ice sculpture, according to a Feb. 20, 1970 Cynic article.

The next evening, two members of Alpha Gamma Rho kake-walked onto the gymnasium floor to receive the trophy for snow sculptures, according to the article.

“Cotton Babes,” was played at the Alpha Gamma Rho and Kappa Alpha Theta houses that night, according to the article.

Percy Wenrich, composer of

On the Sunday evening of the weekend, roughly 800 students gathered in Simpson Dining Hall to watch an impromptu Kake Walk, performed by members of multiple fraternities, according to another Feb. 20, 1970 Cynic article.

During the event, eight to 10 black students from St. Michael’s College in nearby Colchester entered the UVM dining hall in protest Garrison Nelson said.

“If there’s going to be any walking tonight, it’ll be over my dead body,” they said, according to the Cynic article.

Greeks Oppose Revival

Over the next eight years, there was much speculation over whether or not Kake Walk would return, Nelson said.

In an open letter to President Lattie Coor Feb. 24, 1977, Brian Pluff, president of the Greek Coordinating Council at the time, and Marjorie Read, president of the Panhellenic Council, stated their overwhelming opposition to a revival of the Kake Walk.

Nelson also said that when Coor became president of UVM in 1976, he made it clear that “there are three K’s in Kake Walk and it’s not coming back.”

English professor John Gennari also said the spelling was deliberate.

“It was Kake Walk with three ‘K’s’ to look like the KKK,” Gennari said. “At that time, [the KKK] was a perfectly acceptable organization that was thought of as doing good work in controlling the threat of black men doing activity such as deflowering white women.”

Robin Katz, former outreach librarian for the UVM Libraries’ Center for Digital Initiatives, said she felt it was important to examine UVM’s history and helped teach a class in the summer of 2011 titled “Curating the Kake Walk.”

“It’s obviously a sensitive topic that will inspire strong feelings on various sides,” she said, “but it happened at UVM – maybe we could talk about that and think about it a little.”

ALANA student Addy Campbell also said the University shouldn’t forget its past.

“It is a shameful part of UVM’s history,” she said, “but it’s is an event that every student on this campus should know about.”

Junior Drew Cooper said there still remains a lack of diversity at UVM that makes faculty and administrators unable to truly see the complexity of the black experience. Not only has the Kake Walk influenced where UVM is today, but various forms of the event still exist in many institutions nationwide, Cooper said.

“It’s an insular community of privileged whites that only differ from their predecessors in that they appear to feel guilt over what used to occur here,” he said.

He said UVM and Vermont shouldn’t be looked at as “post-racial,” as it’s often perceived.

“UVM likes to masquerade as a progressive school,” he said, “but the reality is that the administration is predominantly run by white people who haven’t the slightest idea of how to handle issues of race.”

It took a while for UVM to expunge the tradition of the Kake Walk from their reputation, Nelson said.

“You can certainly see that in the statements of recent presidents who have made a point of championing the amount of diversity that’s on campus today,” he said. “I see that as a sort of belated response to the hangover of Kake Walk.”

Junior Kiana Gonzalez, a member of ALANA, said despite UVM’s past, she appreciates the progress the University has made in the name of social justice.

“We have so much to do as students to continue advocating for this topic,” Gonzalez said, “but I believe that UVM as a whole has definitely created, and will continue to create, a welcoming place for all identities.”

Heading-Grant said UVM has had a “bittersweet” history with diversity like other colleges and universities in the U.S.

“However, we have worked steadfastly and hard to move further away from a painful history of discrimination and bias seen during the Kake Walk era to one that today advances a positive climate of diversity and inclusivity through visible leadership, resources and institutional commitment,” she said.

Part 1 Continued: After the Kake Walk

This article was awarded first place by the Associated Collegiate Press as the 2016 Diversity Story of the Year on Oct. 22, 2016.

hal Greenfader • Oct 19, 2020 at 3:52 pm

In 1954 Don Forst published his first article against Kake Walk in the Cynic. His successor Brad Gordon kept up the heat during 1955, Both were fraternity brothers of mine at Phi Sigma Delta. They truly deserve mention in any article on the subject.

Then again, so do I.

I was strongly against any cancellation of Kake Walk. “Hell, it’s just tradition,” I remember exclaiming, as I joined the army of insensitive

troglodytes who rallied against change.

I must also admit, that when watching the video clips of the Kake Walkers in this article, and hearing the strains of “Cotton Babes,” a little chill… hell, a big chill ran up my spine.

Mea Culpa,

Hal Greenfader