A snacking style called “girl dinner” emerged on TikTok this summer, popularizing one-dish-wonder meals.

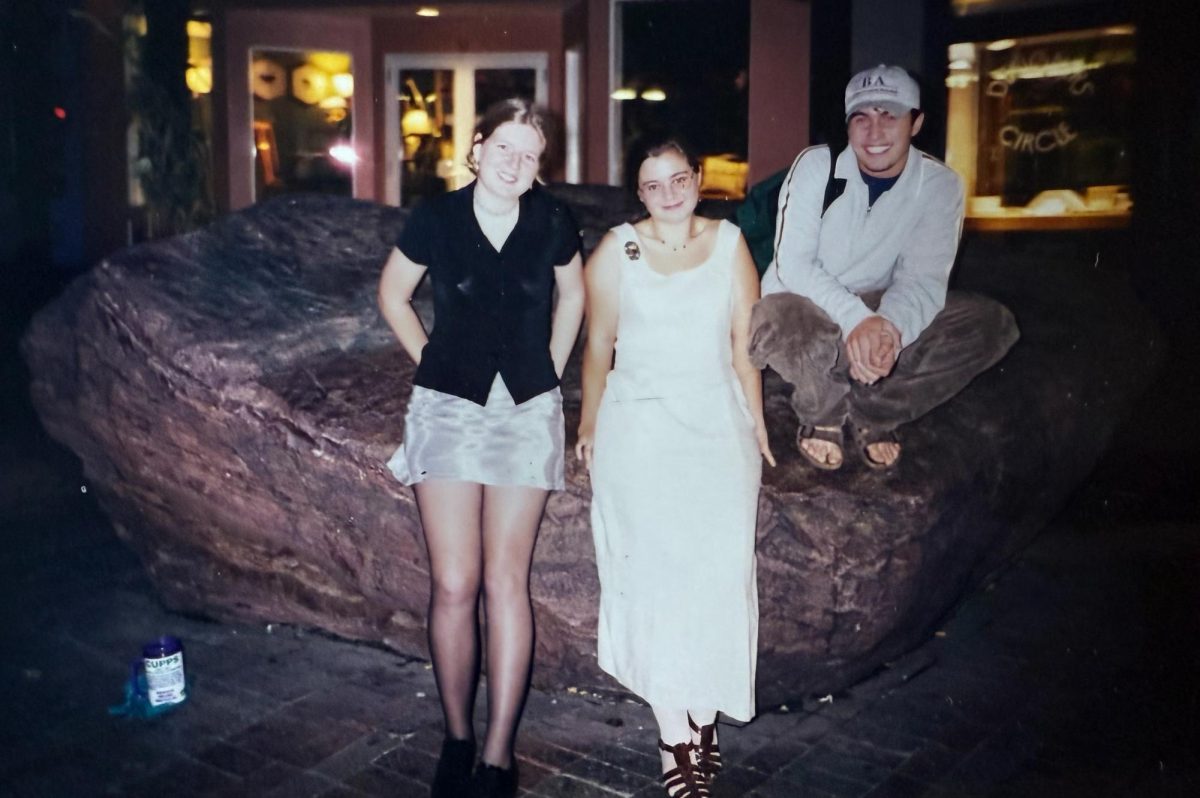

Olivia Maher, a Burlington-based showrunner’s assistant living in Los Angeles, who was home in Vermont due to the WGA strike, posted the original video of her charcuterie-style supper: bread and butter, a block of cheese, grapes, pickles and a glass of wine to wash it down.

“I was just standing in my kitchen at my counter eating salami and grapes and I just went ‘I can’t be the only person that does this,’” she said.

Her video inspired TikTok users to show off their relatable, low-effort spreads, featuring everything from familiar fixes like microwave popcorn to satirical spins like Plan B with a glass of wine.

The trend even acquired an official jingle along the way, which has 432k posts under its sound on TikTok, as of Oct. 22.

“It’s really cool to watch a community form behind it on my video alone,” Maher said.

“Girl dinner” is a low maintenance meal made up of whatever a person wants to have, typically a collection of side dishes and small portions that satisfy the exact cravings of the eater and fills them up without presenting as a standard full dinner, she said.

“Girl dinner” reached a wide audience, one key demographic being college students, Maher said.

“We don’t have a lot of time to cook big, extravagant meals,” said sophomore Anais Higgins.

Higgins understands “girl dinner” as light-hearted commentary on how young adults living in apartments or on campus can only throw together easy meals, she said.

“The times the dining halls are open are not conducive to everybody’s schedules, and they definitely don’t have a lot of options that are accommodating for different dietary needs,” said senior LivingWell employee Hayley Wrede.

Wrede added that after working on campus their first year, they would snack alone in their dorm because the dining hall hours did not line up with their schedule.

“Girl dinner” becomes problematic when it’s not fortifying enough to fuel the person’s body or brain or when motivated by a desire to change their body size, said Amy Sercel, a Registered Dietitian at UVM Student Health.

“I think the most important thing is that [students] are getting the volume of food that they need to make it a full meal,” she said.

“Pretty much everyone can agree that diet culture is everywhere we turn,” Sercel said. “It gets in the way of self-care for students and perpetuates eating disorders and disordered eating.”

Young adults are especially vulnerable to diet culture, with eating disorders typically beginning between 18 to 21 years of age, according to the National Eating Disorders Association.

Maher responded to commentary online about “girl dinner” romanticizing eating disorders or reinforcing diet culture by saying that the big idea is having community with yourself and creating a safe space with food, Maher said.

“We cannot judge based on these little clips,” Maher said. “We don’t know what that person had earlier that day.”

Sophomore Mia Kalish noted that “girl dinner” should not endorse small, unfulfilling snack portions.

“True ‘girl dinner’ really means a bunch of scrambled silly food items that come together to make a full meal,” said Kalish.

Another critique from TikTok users about “girl dinner” was the gendered prefix, which plays into a broader internet trend, including “hot girl walk” and “girl math.”

“It’s very empowering to have expressions like ‘girl dinner,’” said senior LivingWell employee Isabella Dunn, “but I also think the patriarchy just reinforces [it].”

“Girl” trends are noticeably easier than the traditional way of doing something, which can feel degrading sometimes, Dunn said.

Maher responded to similar commentary online that branding girl dinner as a “girl” activity is a cute way to name this more feminine behaving trait, but anyone can participate, Maher said.

“‘Girl dinner’ for me has really been societally a representation of breaking down gender roles” said sophomore Meredith Williamson.

Williamson finds comfort in “girl dinner” freeing women from being the expected nurturer and banding together in self-indulgence.

“You almost feel like you’re getting away with something, but you’re not, you’re just letting yourself enjoy something,” Maher said.

Maher used her newfound time on strike this summer to revel in the success of “girl dinner,” which brought her new opportunities, conversations and community.

In an effort to give back to Vermont after disastrous flooding this summer, Maher launched a merchandise campaign, giving a portion of the proceeds to the Intervale Farmers Recovery Fund.

The Intervale is working toward building a sustainable, community-driven food system that can withstand climate catastrophe both locally and across the state, according to their website.

“I chose the Intervale because they are an unbelievable community resource,” Maher said, “It’s just really special to be able to give back.”

Maher’s go-to girl dinner is “charcuterie, but hold the board”: various cheeses, cured meat, some fruit, bread and butter.

“At the end of the day, it’s just a celebration of food. If you’re feeding yourself, that should be celebrated,” Maher said.