SAWYER LOFTUS/The Vermont Cynic

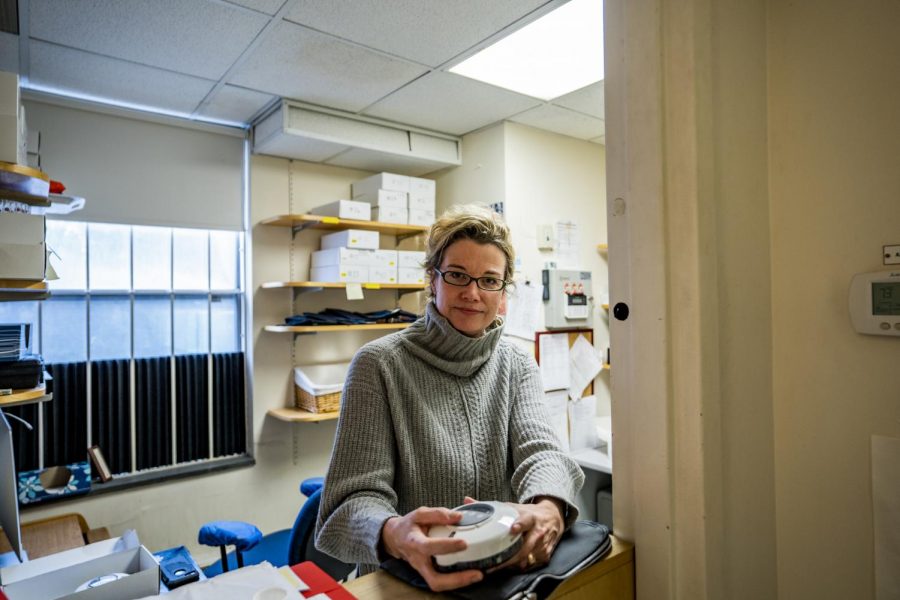

Stacey Sigmon holds a “medi wheel” device in her clinic in the Vermont Center for Behavior and Health, Feb. 3. The new UVM Center on Rural Addiction is dedicated to addressing the opioid issue within rural communities through developed research.

This woman’s research saves lives: meet the director of UVM’s Center on Rural Addiction

UVM researcher leads fight against rural opioid crisis

February 11, 2020

At Christmas this past December, Dr. Stacey Sigmon and her brother sat down together in their hometown of Faith, North Carolina, and made a list.

Together, the two came up with at least 30 people they knew personally who died from either a heroin or prescription opioid overdose.

Sigmon is a clinical researcher at UVM. Her field of study is behavioral pharmacology, a discipline of psychology that studies the intersection of drugs and medications with human behavior.

“We’re all sensitive to reinforcement, whether it’s cocaine or opiates or food,” she said. “For me, it’s potato chips.”

As Sigmon was starting her research career at UVM and finishing postdoctoral work at Johns Hopkins University in the 2000s, she witnessed opioid and heroin use explode from the urban centers of the U.S. into rural areas in both Vermont and her hometown of Faith.

“Some amazing efforts have been made in Vermont on all fronts and by all players in expanding treatment capacity,” she said. “But in rural counties, they still tend to lag behind in treatment availability. And yet I think they tend to surpass urban areas in opiate related overdoses per capita.”

Now, Sigmon is the director of the $6.6 million UVM Center on Rural Addiction, which will provide healthcare providers in rural Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont with the best practices that are being used to stem the impact of the nationwide opioid epidemic.

“The best catch phrase is probably ‘helping patients, by helping providers,’” Sigmon said. “The center will work on making providers more comfortable to treat patients, more comfortable treating a number of patients [suffering from opioid use disorder] and see better patient outcomes too.”

In Vermont, Sigmon’s recent research has shown that technology and medications like Bupenorphine save lives while people wait to get into treatment, said Kelly Peck, a research professor at UVM who trained under Sigmon.

Buprenorphine is used in medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder.

“Dr. Sigmon had this really novel idea, that I think made it a lot easier for people to get effective treatment for opioid use disorder in Vermont,” Peck said. “This idea of using technology as a tool to make it easier to deliver these treatments and using these harm reduction approaches…has been really helpful.”

Sigmon’s idea came to her four to five years ago, when she realized there were 800-900 Vermonters waiting to seek treatment for their opioid addiction, she said. At times, that translated to a two-year waiting list.

Sigmon and her research team began using a device called a “medi wheel,” which is programmed at her research clinic to automatically distribute a single day’s dosage of Buprenorphine, a drug that is used to treat opioid dependent adults.

Sigmon hold a “medi wheel” device. The device is designed to automatically distribute a patient’s daily dosage of Buprenorphine.

“We’d program the time of day that each day’s dose would be released, and an alarm is emitted, and [the patient] can press a button and get that day’s dose,” Sigmon said. “Really, it’s a way to try and allow them to dose at home, but not be at risk of selling, sharing, losing or taking too much at once.”

Peck said he and Sigmon have worked together closely during his time at UVM. Peck runs the day-to-day operations for Sigmon’s interim Buprenorphine study, and Sigmon has helped him find his own research niche, he said.

“She’s been really helpful for me in just gaining some experience in behavioral pharmacology but also in these harm reduction techniques,” Peck said. “Any time you get to work with someone who has these really novel and innovative ideas, you learn a lot.”

Additionally, Sigmon’s work with the Chittenden Clinic, an opioid clinic and part of Vermont’s first in the nation Hub and Spoke Program for treating opioid addiction, has helped shrink the waitlist.

In Vermont, it’s estimated that between 15,000 to 20,000 people have Opioid Use Disorder, according to a January 2020 report from the Vermont Department of Health.

As of November 2019, zero Vermonters were on the waitlist for services offered through the state’s Hub and Spoke Model, according to state data.

In that same timeframe, state data says more than 3,000 Vermonters are currently being treated for Opioid Use Disorder. This is an increase of more than 1,000 Vermonters.

Now, Sigmon’s task of running UVM’s Center on Rural Addiction will not be focused on research, but on spreading the best practices her years of research have developed and giving those tools to doctors in rural Northern New England.

“Think boots on the ground,” she said. “We’re taking these evidence based practices to the rural providers and clinics.”

The center’s home will be at the UVM Medical Center building on South Prospect Street, just on the other side of Waterman Green.

One of Sigmon’s researchers works in their Opioid clinic. This small room is currently where all of Sigmon’s research is conducted. March 1, she’ll move into a new space.

It’s first job is to address opioid addiction, but also all other forms of addiction, like cocaine and meth, which are on the rise, Sigmon said.

Although there will be a physical space, Sigmon said the center’s model will be a hybrid of physical training and a robust phone line system and online database of resources for rural medical providers.

“We’re able to have armies of actual center staff that can truly travel out to the practices in rural counties, armed with 100 medi wheels, 50 Narcan doses and provide hands on training,” Sigmon said. “After that, we can still provide all kinds of support by web or phone or telemedicine platforms.”

Although the first goal is to simply get up and running, Sigmon said she aspires to quickly get the center to a place where it can provide resources at a nationwide level.

The center is set to open March 1.

Kay Francesy Frances Schepp • Feb 14, 2020 at 11:35 am

CONGRATULATIONS. Moving from the research to direct clinical application (especially with a device that can avoid constant travel) is brilliant. I hear only positive comments in my practice.

Kay Frances Schepp