Editor’s note: Alex Strand is currently a student in David Massell’s North American Indian History class. She began reporting for this piece in the fall of 2024, prior to becoming Massell’s student.

Almost three years ago, UVM landed at the epicenter of a statewide controversy over the identity of Vermont-recognized Abenaki tribes.

The University hosted a panel that brought members of Canada’s Odanak First Nation, a tribe of Abenaki heritage, to speak about their history and its relation to the Vermont Abenaki on April 29, 2022.

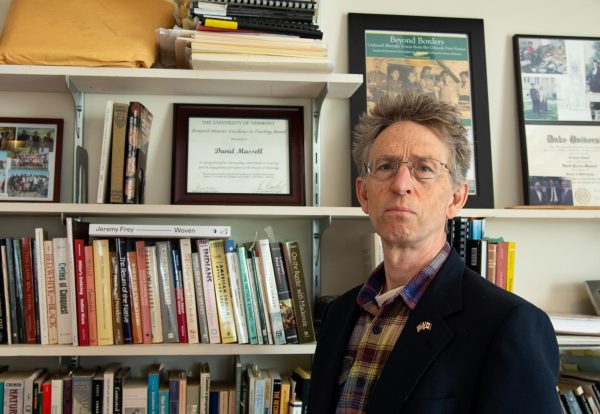

“The names, images, characteristics, histories of Native peoples have been spun and shaped by Euro-Americans for a Euro-American audience,” David Massell, a UVM history professor who introduced the panel, said. “Today, Native peoples speak. We ask all of you to join us in listening to and learning from the Abenaki of Odanak.”

The panel called to attention an issue that had previously not been widely discussed on campus. The Odanak speakers made clear, speaking to audience members in the Davis Center, that they do not view members of the four Vermont-recognized tribes as Indigenous or Abenaki.

“We rose above adversity, and we are told that our voice is not to be heard. We are a victim of colonialism by these pretend Indians,” said Jacques Watso, the Odanak Band Councilor, at the panel. “They will harm real Abenaki to protect their pretend Abenaki cause.”

Soon after the panel, 10 UVM faculty members sent a commentary to VTDigger, noting how little is known about Vermont’s Indigenous history and the complicated cultural landscape — including in their own institution’s classrooms.

“Remarkably, the existence of the Odanak First Nation was unknown to our students, most of our colleagues, and nearly all Vermonters,” stated the UVM faculty.

Since the panel, UVM students, faculty and Vermont Abenaki members have expressed concern about the University’s lack of opportunities for students to learn about Indigenous issues and its failure to approach teaching about the Vermont-recognized tribes.

Rich Holschuh, director of the Atowi Project and spokesperson for the Elnu Abenaki, a Vermont-recognized tribe, is worried that the University has not sufficiently fostered conversations with the Vermont Abenaki.

“Although the Administration has attempted to distance itself from the harm currently being done by a limited number of faculty and personnel, the disconnects and dysfunction continue apace, and the opportunity to bring understanding and restoration among our communities remains unfulfilled and beckoning,” he stated in an email to the Cynic.

Currently, three professors at UVM teach topics related to Indigenous studies. All of those faculty members are white, according to English department lecturer James Williamson, who teaches Native American literature.

“Probably over half, and maybe at some points, two-thirds [to] three-quarters of all the people who are getting a course on Native studies, are getting it from me,” he said. “And I know my stuff, but I’m not Native myself, and I think people should have more than what I have to offer.”

Senior Lucas Roemer is a history and environmental studies double major who has taken multiple courses on Native history, namely a research seminar on Indigenous history. He is also a teaching assistant for Massell’s Native History course.

Roemer believes Native studies are essential for history students as well as the general public, he said.

“Native peoples are often left out of historical discussions, or, if included, are treated as an afterthought or backdrop,” Roemer said.

Some UVM faculty, alongside Isaac Shoulderblade, the First Nations student and community empowerment coordinator for UVM’s First Nations’ Collective, have been working to create an Indigenous studies minor for a few years, said Shoulderblade.

The UVM First Nations’ Collective, a group within UVM’s College of Education and Social Services dedicated to supporting Indigenous students, also announced a scholarship for all students interested in studying and working with Native communities, which is funded by private donors, according to a Feb. 6 Instagram post by the Collective.

“That scholarship is open to anyone who wants to help out Indigenous communities long-term,” said Shoulderblade.

The Abenaki nation, recognized by the province of Quebec, has more than 2,000 members, 400 of whom live in the Odanak and Wolinak reserves, according to their website. They are descendants of Abenaki people who once lived across what is now Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, parts of Massachusetts and Quebec.

“We have survived waves of pandemic disease, multiple colonial wars, the vast reduction of homeland, and forcible assimilation, and we are the sole guardians of that heritage,” stated the chiefs of Odanak and Wolinak reserves in a letter to Vermont conservation groups, urging them to cut ties with the Vermont Abenaki tribes.

The chiefs of each Vermont Abenaki tribe put forward a statement soon after the panel, affirming their existence and recognition by the state of Vermont.

“The distinct historical and contemporary realities within the southern reaches of Ndakinna, our homelands — under the influence of British and French colonial, Federal, and State governments — have brought us to where we are today. Through common experiences of colonization, marginalization, and displacement, our citizens are now found within what is now called New England and points beyond,” they stated.

A 2023 study of genealogical records conducted by Darryl Leroux, an associate professor at the University of Ottawa, concluded that 97.8% of members of the Vermont Missisquoi did not have Abenaki heritage. Leroux also spoke at UVM at another panel hosted by David Massell in May 2024.

Kim Tallbear is a professor of Native studies at the University of Alberta and a citizen of the Dakota Nation. She is a prominent researcher on race shifting and tribal belonging.

Identifying as Indigenous without a clear lineage perpetuates harmful colonial power over Indigenous people, said Tallbear in a 2022 panel.

“They theorize Indigenous peoplehood, sovereignty and anti-colonialism,” she said. “They become thought leaders, institutional decision makers and policy advisors to government leaders with regulatory and economic power over our peoples and lands. They shape academic and public discourse about who we allegedly are, what our lives allegedly look like and what they think should be done about and to us.”

By only featuring the Odanak, UVM’s 2022 panel failed to support the Vermont Abenaki perspective, said Jeffrey Benay, who was a member of the Vermont governor’s advisory commission on Native American affairs from 1991 to 2006 and is now an administrator at the Indian Education Consortium in Vermont.

“Dialogue is key,” Benay said. “The answer isn’t to say that we don’t want [the Odanak] coming on to UVM campus. It would be good for us to be able to talk.”

He detailed the history of the Vermont Abenaki and their ties to UVM, including the Summer Happening, an event in which Abenaki students would visit UVM’s campus. The event ended in 2022, following the panel.

The Vermont Abenaki story was one of low-income people who founded their own preschools, housing projects and non-profits, not of people who were trying to gain state recognition for prestige, he said.

“Odanak just doesn’t talk about this because it doesn’t fit into their narrative,” Benay said. “[The Odanak suggest] that these people are frauds, and that there are just a handful of them, and that all they are interested in is money or prestige.”

The Odanak First Nation attempted to follow up with University administration after the panel’s backlash, including with Patricia Prelock, who was a provost at the time, according to a 2022 email provided to the Cynic.

“Our unceded territory is claimed by two countries and several American states, and now it is being claimed by Vermont’s four ‘tribes’ with increasingly harmful effects to our people,” stated Suzie O’Bomsawin, assistant general director on behalf of the Abenaki Council of Odanak. “UVM needs to take steps to end its complicity with cultural appropriation and fraud.”

The University never responded to this request to meet, which David Massell saw as deeply ironic for an institution with a long-stated commitment to diversity and inclusion, he said.

The University also hosted another panel with administrators and faculty, highlighting its historical ties with the Vermont Abenaki, on April 16, 2024.

Benay wants to understand the experience of students’ education surrounding the Abenaki, especially those taking courses with Massell, he said.

“I’m trying to understand it from a student perspective,” he said. “It sounds as if it’s very black and white, it’s very either-or. It’s a very rigid way of looking at it.”

The Cynic requested Interim President Patricia Prelock’s commentary on the aftermath of the Odanak panel, as well as on the development of the Indigenous studies scholarship.

“A vital part of UVM’s mission is preparing students to be accountable leaders who make meaningful contributions for people and planet,” stated Adam White, UVM executive director of communications, who responded on Prelock’s behalf in a Feb. 12 email to the Cynic.

White did not mention the 2022 panel.

“The First Nations’ Scholarship exemplifies that [mission] in its aim to help empower students to make a positive impact for communities of Indigenous peoples. Whether they go on to pursue work as educators, social service leaders, health practitioners, or in other vital roles, recipients of this donor-established scholarship dedicate themselves to service on behalf of Indigenous students, families, and communities,” he stated.

Massel maintains that if UVM is interested in Indigenous sovereignty, or wants to enlarge their Indigenous curriculum, it has work to do in repairing its relationship with the Abenaki of Odanak and Wolinak first, he said.

“It was and remains my job to explore the historical record with colleagues and students and to share what I find there, regardless of how inconvenient those findings might be,” said Massell at the Vermont state house on Feb. 19, once again introducing the Odanak. “I can and must facilitate evidence-based conversations, even challenging ones.”

Shoulderblade encourages students to remind UVM administration and educators that they are interested in learning more about Native American history, he said.

“The more that faculty and staff are aware that students want Native American studies, the more likely they are to actually go forward with it,” said Shoulderblade. “The University needs to know that there’s a need and that there is a strong enough desire for this.”

More information on the Vermont state-recognized tribes is available on VTPublic’s podcast “Recognized.”