AI writing tools garner concern about academic integrity, education from faculty

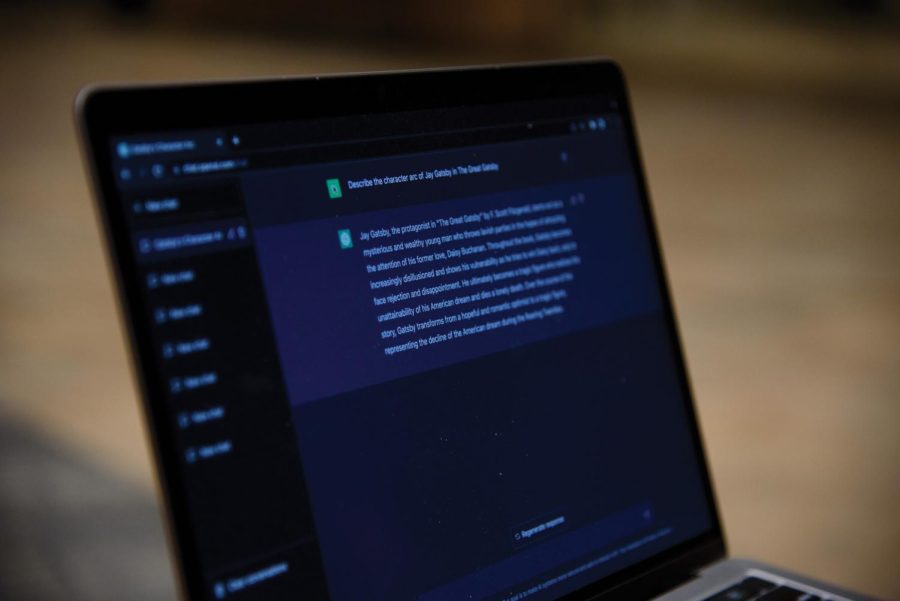

Photo Illustration: Faculty at the University are considering problems and opportunities of new artificial intelligence writing and coding tools including ChatGPT.

Artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT have drawn the attention of University faculty, according to a Feb. 2 email from Deanna Garrett-Ostermiller, assistant director of the Center for Student Conduct.

Faculty and administrators are now considering both the potential problems and opportunities presented by the new technology, she stated in her email.

“I think many of us understand how significant this technology is and that it will be incorporated into many aspects of our daily lives in the future,” Garrett-Ostermiller stated. “Our focus with students is really on their learning and whether/how the technology will facilitate their learning.”

She believes the University needs to consider when AI tools are suitable for use in classes and assignments, and when use of the tools would constitute an academic integrity violation, she stated. She also believes it is important to teach students how to use the tools effectively and ethically.

“There are many other aspects of ChatGPT to consider, including the current limitations and inaccuracies, its tendency to fill in gaps with incorrect information, the potential for harm caused by inherent bias, and ethical concerns regarding privacy and data security,” she stated.

There have been no reports of academic integrity violations related to ChatGPT, she stated. Sanctions for academic dishonesty using AI tools would be similar to sanctions for other methods of plagiarism and would vary based on the incident, she stated.

Some classes may include instruction to students about how they can use AI tools responsibly and ethically, she stated. As this AI technology evolves, additional education concerning AI tools may be needed in the future.

The University’s Code of Academic Integrity has undergone one change related to AI tools, she stated.

“Students may not claim as their own work any portion of academic work that was not completed by the student,” according to UVM’s Code of Academic Integrity.

The end of that policy used to end by referencing work completed specifically by another person, but was changed to reflect AI tools, Garrett-Ostermiller stated.

The need for more significant changes will be reevaluated on an ongoing basis, she stated.

The terms of use for OpenAI, which produced ChatGPT, state in part that users “may not […] represent that output from the Services was human-generated when it is not.”

AI tools have caused concern in the computer science department, said Clayton Cafiero, a senior lecturer of computer science.

These AI tools give students the ability to answer questions using the AI, Cafiero said. He said he has seen ChatGPT write entire short programs, consisting of 10 to 50 lines of code, with high accuracy.

“There are many of us in the department who have already tried ChatGPT out with assignments we’ve written previously,” he said. “And in many cases, ChatGPT either nails it or comes pretty close.”

Cafiero specifically calls out this use of AI tools as a violation of UVM’s Code of Academic Integrity in his syllabi, he stated.

Along with academic integrity issues, another concern is that students will have trouble learning if they opt for using AI, Cafiero said.

“If they bypass the learning process, which is struggling with the material, by using something like ChatGPT, then they’re kind of cheating themselves out of an education,” he said.

Another issue arises when AI sometimes offers what seems like a plausible solution to a beginner, but is actually completely wrong, Cafiero said. A student may submit the answer to a problem for an assignment, but would have no idea if it was correct or not.

Right now, the computer science department is relying on trust and is not currently using any measures to detect AI in student work, he said. Homework assignments submitted by students are auto-graded, but either the instructor or a teaching assistant look at all submissions before finalizing the grade.

Minor changes to the structure of some computer science courses, such as modifying the weighting of assignments, are being implemented as a result of emerging AI, Cafiero said. No other changes to his class are planned for now, he said.

In his introductory programming course, Cafiero has changed the weighting of assignments to lower the weight of homework while increasing the weight of in-class assignments, such as labs, he said.

The hope is that by making homework assignments carry lower stakes, students will be more encouraged to do the work themselves rather than use AI, Cafiero said. He has yet to catch any of his students using AI in their work.

AI tools could be useful for students in some contexts, Cafiero said. They could help students better understand concepts of programming by providing clear explanations and examples, allowing them to more easily apply them into their work.

“That’s a perfectly legitimate use of it,” Cafiero said. “The problem is if a student decides to submit code that’s generated by ChatGPT and put their name on it.”

Cafiero is not sure how he might integrate AI tools into his curriculum, but believes it is worth considering, he said. They could be useful for instructors to model legitimate use of AI tools.

“I’m hopeful that the legitimate uses prevail, they carry the day, and that some of the darker, seedier sides of this don’t really get to be a huge problem,” Cafiero said.

English faculty are aware of the emerging technology, but the level of concern is fairly low right now, said John Gennari, professor and chair of the English department.

“Within the English department, there’s always been a sense that the kind of writing that we require really does not lend itself very well to what we understand these services are doing,” he said.

The department has always felt that the kind of assignments they create are specific enough to each class to make it difficult to use AI tools to cheat, Gennari said.

Still, faculty are monitoring the emerging AI tools to see if they become an issue, Gennari said.

In seeing how these AI programs work, they could prove useful in a lesson about thinking through an essay or matters of tone and grammar, he said.

Gennari would be willing to use AI tools in his classes if they can improve teaching, he said.

“That would call for some really interesting discussions about the matter of academic integrity and what constitutes one’s own work and what techniques or approaches professors have to take to maximize the kinds of skill development and knowledge advancement that their classes are for,” he said.

There are currently no measures in place to address the use of AI tools specifically, he said. Depending on how the technology develops, additional measures may become necessary.

The English department does not want to implement anything that will harm relationships built on trust between faculty and students, Gennari said.

“In the English department, we are not interested in any kind of surveillance of our students,” he said.

This refers to actions like searching online for phrases in students’ papers to check for plagiarism, he said.

“That’s a mindset that kind of corrupts the integrity of the learning process,” he said. “It really threatens to undermine the climate that we try to produce in the classroom.”

Gennari has not had any reason so far to suspect his students of plagiarizing by using AI tools, he said.

Some educators are taking the position that it is not worth it to put in extra time to determine if students use AI tools because the consequences will present themselves to the students in the future, said Andrew Barnaby, an English professor.

“Some teachers might think, if you want to turn to this method, do it,” Barnaby said. “It’s just in the long run, it’s going to not help you and you’re throwing away your education dollars.”

Others are more concerned about the academic implications of AI tools and think more steps should be taken to deal with it, he said.

Barnaby is interested in learning about potential ways to stop the use of AI in faculty workshops, but he is not interested in spending lots of time trying to catch students using it, he said.

“I think I’m slightly more inclined to let students decide for themselves and hope that they make the decision to value their own education,” he said.

He feels optimistic that most UVM students would not turn to AI in their work, Barnaby said.

“I would hope that students would be up for the challenge of ‘I don’t want to [use AI], I would rather create a paper—my own paper—flaws and all, that’s mine,’ rather than giving it over to a machine,” he said.

Faculty could decide it is too time consuming to try to catch students using AI given their other responsibilities, he said.

“So I might say [in class], ‘some of you are going to break the rules, and I might occasionally catch you,’” he said. “‘But you could break the rules and I won’t catch you. And is that who you want to be?’”