STI stigmas persist for LGBTQ+ folks

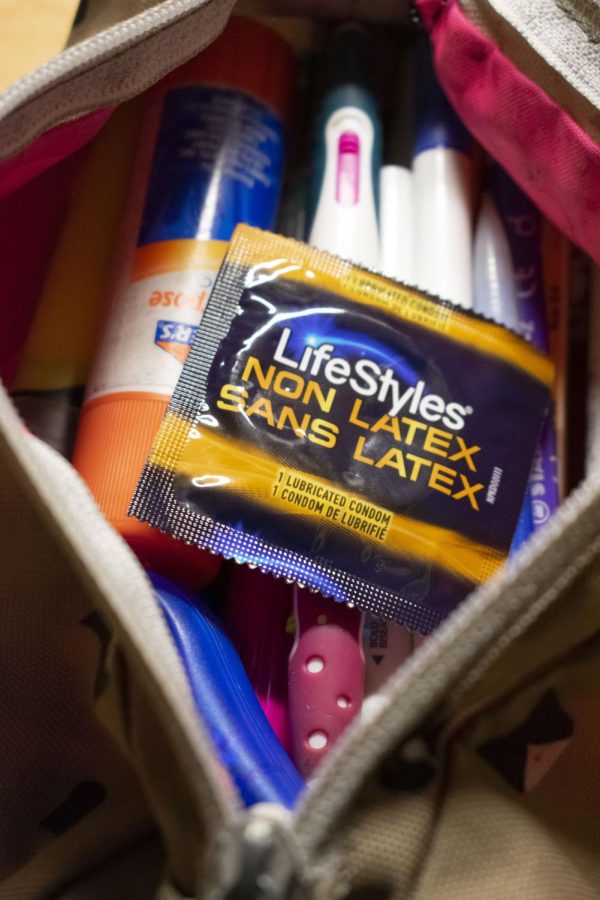

A condom from Living Well in the Davis Center pictured with school supplies Dec. 3.

While sexually transmitted infections are a prevalent reality on college campuses, the issue is often shrouded in stigma, said Jenna Emerson, health and sexuality educator at the Center for Health and Wellbeing.

A lot of STIs can be managed early, though they can become dangerous when left untreated, Emerson said. Members of the LGBTQ+ community face greater blame for contracting an STI than straight identifying people, which can result in queer folks’ avoidance of medical care.

“What we want is to destigmatize any testing and we want it open and available to all,” said Sharon Glezen, a physician at the Center for Health and Wellbeing. “I think that there are disparities in people in different communities feeling comfortable accessing appropriate sexual healthcare.”

One of the biggest issues contributing to misinformation and stigma stems from sex education in high schools, which often promotes fear-based learning, Emerson said.

Margot Wladyslawski, a queer identifying first-year, said sexual education at her Catholic high school was focused on abstinence, with some information about STIs and sexually transmitted disease transmission.

“[My high school sex education was] really bad,” Wladysawski said. “I say this as a member of the LGBTQ+ community, from what I’m seeing and what I’ve experienced, like, I think there definitely is a stigma.”

Elizabeth Cook, a bisexual identifying junior from Kentucky, said her high school sex education was very heteronormative and not at all informative.

Henry Crawford, a heterosexual identifying first-year from Vermont, said his sexual education was extensive in middle school, but far less comprehensive in high school.

“[There is a] stigma around being infectious because of who you love and who you have sex with,” Emerson said. “Nonbinary, gender-noncomforming and trans men and women already have a lot of mistrust with medical institutions.”

Student Health Services has a handful of queer providers, but she also advises queer students to visit the Prism Center for additional resources, Emerson said.

The most common STI tested for at Student Health Services is HPV, followed by chlamydia, Glezen said.

“We have different ways that people can access STI testing,” Glezen said. “You can submit a questionnaire to a nurse and if you meet criteria for being essentially low risk, then [the nurse] can order lab testing without even a clinician visit.”

Someone who is high risk might have a partner who has an STI, while someone who is low risk is just testing for additional security, she said.

Emerson said she also distributes safer sex supplies and provide education to students through various initiatives, such as the safer sex goodie bag, which contains a variety of supplies, from lube to dental dams. She plans to expand these offerings soon, possibly next semester.

Living Well, a program of the Center for Health and Wellbeing, will begin offering care packages to students who received a positive herpes test result with affirmations, stickers and resource cards, Emerson said.

After a diagnosis, the most important step is self-compassion, Emerson said.

“You will find love if you want, you will have pleasurable sex if you want, you will have sexual partners if you want,” Emerson said. “It might just look a little different.”

Students can access STI testing at the Center for Health and Wellbeing by scheduling an appointment through MyWellbeing, according to their website.