Walking through Waterman green on a January evening can be both a fascinating and eerie experience.

A cacophony of caws and wing flaps fill the soundscape as dark figures cover the sky in erratic patterns.

The crows of Burlington’s winters are a spectacle that some have come to love.

Anthropology professor Luis Vivanco is one of those crow lovers. Crows are a passion of his beyond his professional work: watching them, recording them and sharing stories about them.

“They’re the wildlife in our midst that creates a spectacle, the spectacle of that so-called ‘murder of crows’ in the winter,” he said. “Everybody knows about it.”

While American crows are resident in Burlington all year, their flocks of up to 3,000 birds are on display from about October to early spring, reaching peak numbers in the coldest part of the winter, according to a May 1, 2023 Vermont Public article

The crows form these flocks to avoid conflict with other birds, reduce stress from low temperatures, better protect themselves from predators and maximize feeding efficiency, said Michael McDonald, wildlife and fisheries biology lecturer in the Rubenstein School.

They have specific trees they flock to around the city, usually a very old conifer that can fit the entire flock. Their haunts change from year to year, but recently it’s been the Hill Section of Burlington and the Gutterson garage area of UVM campus, McDonald said.

Cities attract crows because of their fragmented landscapes, abundant food sources, protection from predators and warmth from urban heat islands, according to a March 15 article from the Atlantic. Anthropogenic influences like garbage and landfill facilities draw them in as well, McDonald said.

Corvids, the bird family that includes crows, have been fascinating humans for millennia. They appear in mythology, often as tricksters or a sign of death, according to a Nov. 15, 2015 Corvid Research article.

“Corvids have been these mythical figures in so many different cultures because of their intelligence, their ability to recognize patterns, their ability to adapt the collective nature of their lives and the ways in which they communicate with each other and pass information across generations,” Vivanco said.

People have even gone on to develop relationships with crows. Often these stories surround children in reciprocal gift-giving relationships, according to an Oct. 1, 2015 BBC video. Crows’ intelligence is often a spark for those who become interested in them.

“My entry point into crows and my weird obsession with corvids is [that they] are these birds that have sophisticated social relationships and ways of passing on information and knowledge,” Vivanco said.

UVM’s campus is a prime roosting spot for the crows in winter. Some students notice this and will ask McDonald about the crows in his ornithology class.

“I often have people ask me, ‘What’s going on with all the crows?’ My initial reaction is, ‘Oh, is there something new happening with all the crows?’ And it’s like well, it’s new to the person who observed it,” he said.

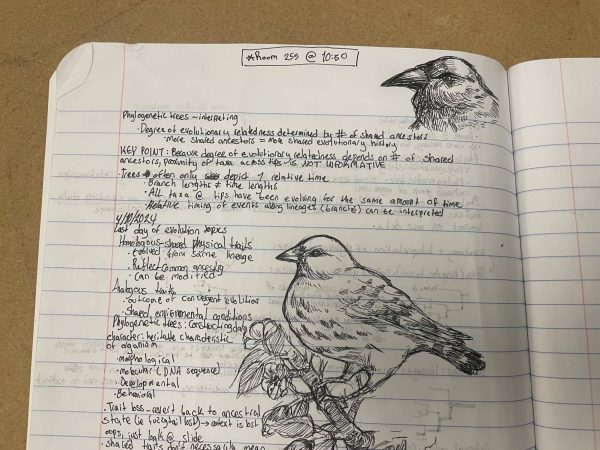

(Sophia Balunek)

Junior Bella Gaffney is fascinated with the crows and often draws them in their notebooks.

“Some of the first birds I really liked to draw, just because they were so big and so distinct, were fish crows,” Gaffney said. “It’s just something I do now. It’s like a reflex almost; I sit in class and if I have nothing else to do, I draw birds.”

Gaffney started paying attention to the crows during her walk home to Living/Learning as a first-year. She noticed them in the winter when they would be louder than usual. She’s watched them move around as she’s moved from Living/Learning to Redstone to off campus in the Hill Section.

“I feel like it’s something that a lot of people have, this crow awakening moment, where they notice the crows in a big group for the first time,” McDonald said. “They’re an entry into an interest and curiosity about nature and natural science that seems to be really special.”

Vivanco enjoys the crows’ “rhythmic cacophony” and feels honored when they decide to roost in his backyard.

“It’s always a really exciting gift to me [when] it’s like 5:30 a.m. and suddenly you wake up because the crows are all in your tree,” he said. “That excites me. I’m like, I want to go see. Where are they? What are they doing? Are they up there? How many are here?”