Do Confederate monuments have artistic merit?

October 4, 2017

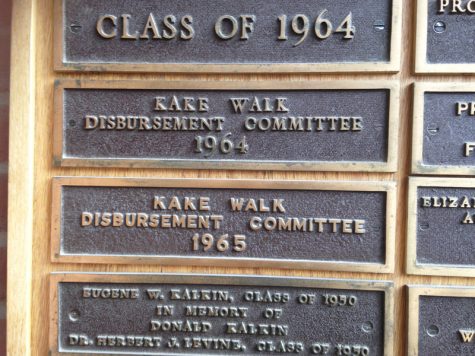

A plaque dedicated to the Kake Walk Disbursement Committees of 1964 and 1965 hangs outside the Bailey/Howe Library. The plaque was removed Sept. 28 after student diversity leaders discussed racial injustices on campus with President Tom Sullivan.

In recent months, Americans across the country have been questioning the definition of art and the purpose of monuments in our time.

When UVM’s Black Students Union presented a list of of demands to President Tom Sullivan on Sept. 25, it caused this national conversation to come knocking at UVM’s door.

Amongst the demands made by the BSU was a request for the re-naming of the George Perkins Building Sept. 25.

This monument pays tribute to the former professor, dean and interim president, according to Sullivan’s email response to the UVM community Sept. 29.

Perkin’s son, Henry, was an active participant in the eugenics movement, according to the email.

The BSU’s demand for change is timely, coinciding with the analysis of Confederate monuments by art historians across the country.

When asked if these monuments should be kept in place for their artistic value, Kelley Helmstutler Di Dio, a professor of art history and associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, firmly said no.

“They have some historic value, but 99 percent of them have little artistic merit,” Di Dio said. “These monuments were mass-produced and put up in a time when the South was trying to figure out race relations.”

Her research has been focused on sculpture for the majority of her professional career, therefore she knows its value and purpose, she said.

The Society of Architectural Historians has the same view as Di Dio.

“This is not a controversy about art or its censorship. The monuments were not intended as public art,” according to the Sept. 13 article by the organization.

There are a few historians, though, who believe the Confederate monuments are significant to the art world.

We should always be revisiting why things exist, especially the names of historical buildings and other art on campus.

— Kelley Helmstutler Di Dio

Hollis Robbins, a humanities professor at John Hopkins University, said many of the monuments are works of art, according to an Aug. 18 New York Times article.

Robbins said that it is important to understand that many of the monuments’ creators did not have political motivations, but rather aesthetic ones.

For example, the statue of Stonewall Jackson in Charlottesville, Virginia was crafted by renowned sculptor Charles Keck in 1921, according to the SAH.

But just because the artist of the Jackson statue was well-known, the monument does not belong in its current, very public location.

“[It] belongs in art museums, which are full of aesthetically pleasing images of unsavory people,” according to the SAH.

Di Dio, speaking as a former curator, said the monuments should be placed in museums only if they were described in the right context.

“I think they would be perfectly placed on Civil War battlefields or Confederate cemeteries, since those are a huge part of the tourist industry in the South,” she said.

Di Dio grew up in Virginia, and a trace of a Southern accent still lingers in her speech.

“I know what they teach in Southern schools,” Di Dio said. “And this is a part of American history that no longer needs to be celebrated.”

It was all about Jim Crow, she said, because the Confederate monuments functioned as a form of control over newly freed blacks, decades after the conclusion of the Civil War.

Many of the monuments in the South were funded solely by lone individuals, powerful people who shunned the voices of African Americans and even most whites, the SAH article said.

Di Dio affirmed the presence of a link between the BSU’s request and the recent protests for the removal of Confederate monuments.

“We should always be revisiting why things exist, especially the names of historical buildings and other art on campus,” she said. “We must be really transparent about how images are represented to the community.”

The monument debate is far from its conclusion, but these discussions about what art is, and what message it conveys, are essential to the success and forward progress of the nation.