Following the Calling: The Cynic reviews Boston Calling

June 3, 2018

Natalie Portman was seated upon a platform stage in the Arena of the Harvard Athletic Complex in Cambridge when the noise started.

Hundreds of baffled festival-goers watched her engage in a Malcolm X-dedicated spoken-word performance while a strange, silent short film from 1930 called “Hell-Bound Train” was projected above her.

The screening was just one part of the “Natalie Portman & Friends” programming going on inside the Athletic complex, where the ninth edition of Boston Calling took place this year.

Portman, who graduated from Harvard in 2003, has an emotive, ethereal, Academy Award-winning voice, which contrasted images of the Devil shakily dancing across the screen, but it cannot compete with the perplexed buzzing in the bleachers.

Just moments before, musician St. Vincent was on stage performing her ghostly score to another short film, emitting only synths and bizarre microphone tapping throughout the intense screening.

The audience members — many of whom were probably only in the air-conditioned building to escape the sun and see a famous face — weren’t quite sure what to make of it all.

Some of them engaged in the spectacle, their hands politely on their laps, eyes fixed on the movie star. But some were less game, and instead adjusted their flower crowns or finished off plates of fried cheese. Others simply hid their phones under the table and checked Instagram.

It was a Saturday afternoon, and chatter began to grow during the performance as the crowd became indifferent, impatient and underwhelmed. Some even vacated the bleachers, stomping for the exits and following the thumping beats that came from the musical sets going on outside.

Toward the end of the short film, a drunk man on his way to the stage at the north side of the festival passed by the arena entrance and hollered inside, “I love you, Natalie Portman!”

It seemed to be just one moment in which this year’s Boston Calling — relatively new in only its fifth year (and only in its second time at this more spacious location, held before at City Hall Plaza downtown) — grappled with the challenge of creating a unique festival experience while hosting unsure festival-goers.

Boston Calling opens its doors on Friday. It is the festival’s second year at Harvard Athletic Complex in Allston.

The day before — on the first day of the fest — I arrived to a Boston on fire.

Memorial Day weekend is, for many, the commencement of summer, the first hot city excursion of the season. It is the sedated, congested kind of weekend where population, traffic and temperature all spike.

It is a weekend of graduations in the city, of young people in caps and gowns on the Green Line with their elbows on their knees, tapping their feet. It is a weekend of pearl and floral print, of white sandals and a sleeping toddler over the shoulder.

After a connection to the Red Line, the ride to the Harvard Square stop was dark and deserted and quiet and thoroughly unexciting. Two young girls, obviously headed to the same place as me, sat across the train with dark lipstick and perfect witchy hair and had a hard time keeping their eyes open.

It seemed closer to a disheartened ride along the river Styx than a dizzying delivery to my first ever music festival, one of the most anticipated New England music festivals of the summer season.

When we arrived, I followed Clarks combat boots up into the light, and moved with the orange-wristbanded folks through the cobblestone streets of hip bars and trendy shops toward the ruckus of the festival.

I followed them over the bridge, past the Harvard gates and beyond the check-in point into the actual festival grounds where, almost at once, it became a weekend of Hawaiian button downs and 35mm point and shoots.

When crowds first enter the fest, they are greeted by a loud, yellow arch entrance that reads in big, bold lettering: “BOSTON CALLING — YOU ARE OUR PEOPLE.”

It’s a puzzling welcome, one that stays in the brain the more the slogan pops up around the festival. Who, precisely, are these “people” that belong here at this “Calling?” What constitutes the Calling? Will these people follow that Calling?

It’s as if, in here, you can elevate, reach towards a vague, glossy light that no one without the festival wristband can.

Inside, there were merchandise booths and a slew of sponsors setting up shop for the weekend: IKEA’s “Food and Music Lab,” a Subaru of New England playground of sorts and an exclusive, elevated party-porch hosted by Barefoot Wine.

There was also an outrageous array of food and beverage vendors — all stacked plentiful with festival volunteers waiting expectantly to serve a very diverse, and very Boston, lineup. There was the expected parade of staples: trays of aluminum wrapped cheeseburgers, overflowing chili dogs, greasy wet fries, soft pretzels. But it’s the other food options which gave the first hint to the festival’s showy attention to the commercial experience: Union Square donuts, The Chubby Chickpea’s falafel, brisket bowls from Firefly’s BBQ, pierogis from Jaju, New England clam chowder, lobster rolls, dumplings, oysters, the much advertised Veggie Dogs from IKEA Foods.

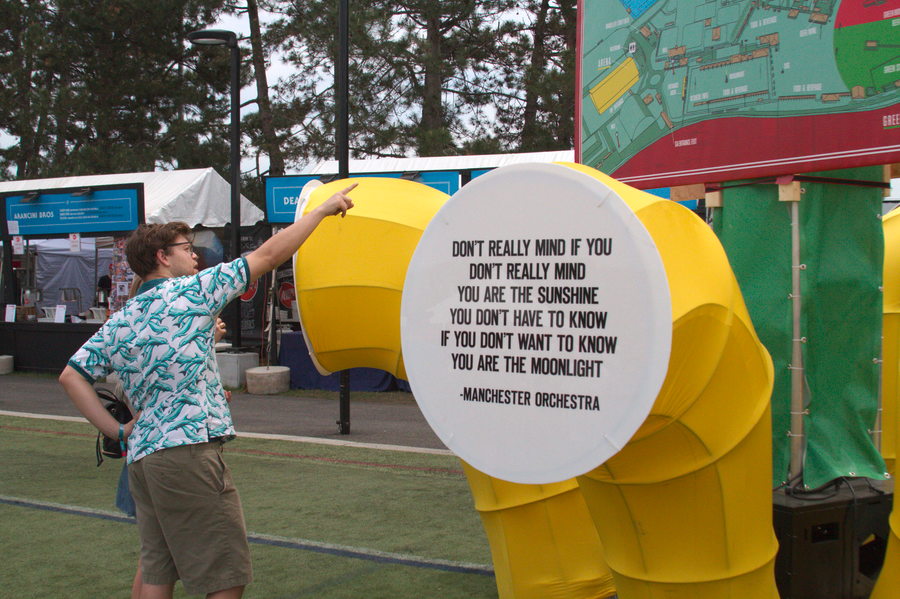

Farther inside, early-birds posed next to sculptures displaying the lyrics from some of the featured artists of the weekend, lyrics which quite directly allude to the romanticized and self-aggrandizing quality of the Instagram-ready music festival vibe: “I do what I want / Everybody wants to be a cat / It’s cool to be a cat / Everything the light touches / It’s where I will roam.” – Thundercat.

Everyone toured around the three stages in those first moments, expectations high — there’s the Delta Blue stage at the north side of the complex, while beyond all the food booths, portable toilets and massive ferris wheel, the Red and Green stages stand as twin pillars of the south side.

The crowds seemed to be preparing for something, adjusting their tube tops and ironic fanny packs, outfit-ready, timeline-ready, the first cold IPA of the weekend in their palm.

Festivalgoers refer to a map of the festival grounds. Maps surrounded by art installations displaying quotes from acts playing at the festival were strewn around the grounds.

Last month I went to Coachella without leaving my living room.

I saw, from livestream, Beyonce perform a historic headlining set, at once empowering and expansive, entertaining and political. Coachella, more and more every year, is the reigning music festival, epicenter of festival fashion and dictator of pop culture. It’s influence could be felt even here on the other side of the country.

Waiting for Daniel Caesar’s set, I listened to a young student from Hingham, Massachusetts who is quick to point this out: “Everyone’s just trying to recreate Coachella … Girls go wild for festivals. It’s such an event. It’s almost like the music is second.”

Her friend, a young man in simply khaki shorts and a band t-shirt — a decidedly conservative outfit — sat across from her in front of the Blue Stage and echoed this: “It’s like, chill with your Vans. No more Vans. What the deal is — Tyler the Creator and Brockhampton — they have this cult following who all wear the same exact thing: the rolled up jeans and the Vans and the Golf shirt. I say branch out your horizons.”

The more the group of kids thinks about it, the more they seem to notice it.

“There is like this untapped potential in festivals in general, it doesn’t have to just be a social event,” he said.

And they’re right. You will frequently see girls with glitter on their cheekbones in white Converse and bleached out shorts.

Boys can be found in unbuttoned shirts and green Stan Smith Adidas tennis shoes and leg tattoos of star designs. More than once I spot Miller Lite hats with floral brims that read “THIS IS MY FLOWER CROWN.”

But the Calling was different from Coachella in many ways: it had less of a desert western psychedelic vibe, and more Vineyard Vines gone dirty. If Coachella’s crowd is well-off celebrities and semi-famous internet personalities imitating the freedom-land of 70s era festivals like Woodstock, Boston Calling’s crowd is probably the “local Twitter” personalities imitating those well-off West Coast types, trekking across AstroTurf instead of dust-ridden desert.

Everywhere you turned there was something else that felt like an attempt to put the Calling beyond the shadow of Coachella, both consciously avoiding it and somewhat aspiring to it:

It’s diverse line up is strategically jam packed with both local and prominent acts in a way other festivals don’t seem to do. There are arena shows with Pod Save America — where upon entering you are greeted by volunteers who encourage you to register to vote in the next election — as well as comedy acts featuring David Cross and Bridget Everett. And then there’s Natalie Portman.

It seems the festival wants to create an eclectic and almost highbrow experience, push it’s creative boundaries beyond the festival-as-social-event, but it struggles to reconcile the expectations of certain groups of its attendees (particularly some of the younger ones) who, in some part, may want exactly that.

What I suspect as a result of this tension, the festival has a constant quality of unfocused anticipation attached to it:

I watched listless groups of people migrate from the Blue Stage along the dusty side road to the Red Stage, then pop over to the Green stage next door, finally making their rounds along the food vendors and moving back to Blue once again.

During the shows, half-deflated beach balls were limply tossed around the unsure crowd. Groups of young people scope out sets for a few minutes, take the obligatory Snapchat during the first song of the set, and then snake back through the crowd with unamused gazes.

The press tent was always full: local journalists name dropping with each other — “I totally did that exact same thing to Jamie Lee Curtis, I just hung up on her.” — and the smaller, local acts playing the festival in press interviews do the same: “He’s, like, the ‘Este Haim’ of our group.”

Photographers scrolled through raw JPEGs from the Maggie Rogers set on their laptops, finding the perfect one to upload within the hour, the time of day when their websites get the most traffic.

Festival volunteers in their red staff shirts squatted and press their backs to sweating buckets filled with complimentary beer and melted ice. They grimaced every time a smug college kid with their press wristband, probably their age, if not younger, came into the tent demanding their fourth Sam Adams.

There was something matter-of-fact about the vibe of the place, both casual and bored, none of the wonder or grandeur which is key to the Coachella mythology and seemingly present in all of the pictures you see on social media.

There was no eyes-rolled-back spirituality, no sunset-drenched, rugged-American freedom, which is supposed to accompany the fashion and music, especially in reaction to turbulent sociopolitical times.

There was none of that — all the costumes, sets and cameras present, but with no script. It leads a first-time festival-goer to wonder if the same lack of purpose was present at the other music festivals, too. It only takes a few moments on the Boston Calling Instagram tag to find the probable answer to that.

The air of half-hearted effort was contagious — I chewed on plain, pink hamburgers in the shade under a Truly hard-seltzer sponsored tent, out of the wet heat, my notebook and pen idle beside me. It’s here that I considered the cynical thought: maybe we were “locals” at heart, maybe we aren’t “their people.” Maybe this really was just something to have done over a weekend, one mere bullet point to list when recounting the things of summer when Labor Day comes and goes: “Yeah, I went to Boston Calling but it was boring as fuck.”

When one arrives at this jaded king of thinking, a montage of all the moments where festival-goers seemed unable to get past the artistic displays of the weekend’s acts played in my head. Perfume Genius and his hypnotic, in-your-bedroom-alone kind of dancing. Russian punk protest band Pussy Riot’s song about morning exercises in prison. A sunburnt Southie screaming about how “The National fucking sucks!” stumbling over a hill away from the Red Stage where they play their sunset set.

Perfume Genius performs on the first day of the festival.

But, like I do, I am forgetting about all the good. There were beautiful, picture-book moments over the weekend. Many of them. There was an exciting blend of indie rock, pop, R&B, hip-hop, folk and electronic music. Smooth, short flows of traffic and no lines and those endless options for food, beverage and music were particularly winning.

And there were great acts.

There was an emotional Saturday performance from Brockhampton, clearly reeling after kicking member Ameer Vann out of the band for abuse allegations, which the group revealed over Twitter the next day. There was Pussy Riot’s condemnation of Putin and Trump as members of an “oligarchy union.” There was The National’s soaring “Carin at the Liquor Store” and “Nobody Else Will Be There.” During their set, couples swayed in the dust, drifting into one another.

There was Maggie Rogers’ absolute joy, bursting onto stage in a starry suit and cape, hair swinging, glitter on face. There were The Killers, crashing into their set, boldly opening with “Mr. Brightside.” There is even the ferris wheel — granted, $10 a pop — which caused one to easily imagine stomach-flutter, tender magic, if on the ride with somebody special.

There was Perfume Genius and his joyous, slow gyrations and his transcendent musical noise.

There was the neon-leather, pill-popping set from St. Vincent and her band. There were music-loving parents with their toddlers in heavy duty headphones.

I watched the golden Boston sun slip through the stage while Perfume Genius’ crowd sucked on marijuana lollipops and squirted sunblock on Irish-white arms. I watched a lanky teen with braces, face acne and a VIP wristband make fun of the joyful, queer display with his best friend until, finally, they stopped ironically head bobbing and gave over to the explosive “Slip Away,” dancing and disappearing out of sight into the crowd.

The crowd cheers after a performance at the Red Stage.

The salvation of it all, I suppose, was that sincere creative output.

I loop back to Portman. For the last section of her Saturday programming, she invited Leikeli47, the masked New York rapper who played earlier in the day, for a most exciting performance.

In army outfits, she was joined by her militaristic backup dancers and spit bars while four short films were screened behind them. Titles like “Consequences of Feminism” from 1906, as well as “A Sticky Women” juxtaposed swaggering, empowering, contemporary lyrics: “Dandridge, Grace Jones / Pay rent or own homes / Buffy Khan, champagne / Kelis is god, so is Beyoncé / Kelis is god, so is Leikeli / So what I got a attitude? / Bitch, I got a attitude.”

At one point, author Zora Neale Hurston’s fieldwork footage is played. Images of a church in Beaufort, South Carolina were accompanied by a poignant song. In one moment, three women inside of the church stand for a prolonged period of time, and it created a moving combination with the lyrics the performer attaches with it: “Black will never die.”

After they finished, the crowd in the Arena goes wild.

Going forward, more exciting creative experiments like this will help strike the perfect balance between the political, the commercial, and the creative, so much so that it will not just feel relevant, but absolutely vital to these times, much like this collaboration between Leikeli47 and Natalie Portman here.

The more Boston Calling separates itself from the vague, unfocused nature of music festival culture, the better.

It seems that St. Vincent summed the weekend up perfectly in the “gay version” of Slow Disco, a standout from her record “Masseduction” and the closing song of her set:

“I’m so glad I came / but I can’t wait to leave.”