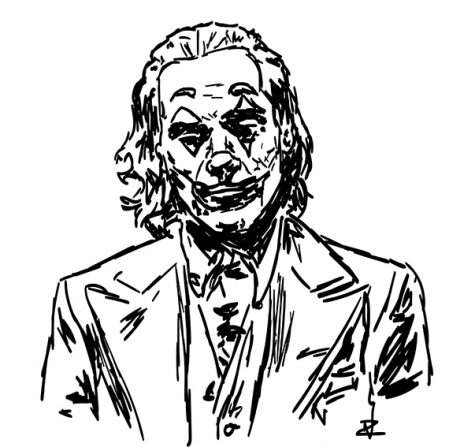

“Joker” evokes sympathy for the ultimate anti-hero

October 25, 2019

A roar of laughter erupts from a dimly lit comedy club. As the comedian sets up the next joke, one distinct high-pitched cackle inappropriately isolates itself from the crowd.

This sad and lonely man with no sense of humor is soon to become known as the infamous villain, the Joker. The movie “Joker,” released Oct. 4, follows his horrific descent into madness.

The real horror in the film derives from the cognitive dissonance, or moral conflict, we feel upon the realization that we are rooting for an anti-hero that represents some of America’s most feared political topics: terrorism and gun violence.

Joaquin Phoenix’s portrayal of the “Clown Prince of Crime” tells the origin story of Arthur Fleck, a man who is broken by a society that does not value the needs of its underprivileged citizens.

Fleck makes a living as a hired clown, aspires to be a famous comedian and suffers from depression and an uncontrollable laughing condition.

Any hope of becoming a standup comedian is crushed by the criticism of those he admires.

Even Flecks’s own mother asks, “Don’t you have to be funny to be a comedian?”

Upon the realization that his attempts to do good are useless, he is confused and hurt. Arthur acts out in self-defense when he is harassed on the subway, and his violent actions gather support from an underground anarchist political movement.

For the first time ever, he is noticed.

From the first scene, I was already emotionally attached to Fleck. His entire life, he believes that he exists to make others happy, yet not only does he struggle to have any personal connection to anyone, he is consistently abused.

Nobody listens to Fleck’s cries for help, not even his own therapist. He has to explain to her, “You don’t listen. For my whole life I didn’t know if I really existed — but I do. And people are starting to notice.”

This is reminiscent of the motives of perpetrators of gun violence. People that cause these horrific acts of mass violence are people like Fleck, who go unnoticed.

“The worst part about having a mental illness is that people expect you to behave as if you DON’T,” Fleck writes in his joke journal.

I found myself craving justice for Fleck through his violence and chaotic destruction against Gotham City.

However, from the beginning of “Joker,” Phillips provokes an empathetic view of someone so broken down by society, that when he reacts, you just feet a release.

This, as a viewer, causes a moral dilemma, and strikes me as being a most powerfully horrifying realization upon noticing my emotional involvement as the film progressed. The ability to create this highly political subplot is one of the film’s greatest strengths.

Through its entertainingly blurred depiction of reality, “Joker” takes something undoubtedly terrible and makes it digestible to an audience that ends up praising the protagonist’s goal.

Overall, “Joker” provides a psychological ride all the way up to Fleck’s unsettlingly telling last line: “I’m just thinking of a joke. You wouldn’t get it.”