Mold, maggots, decrepit facilities, unsanitary conditions, medical neglect, reports of sexual assault, misconduct and retaliation from prison staff—the list of reported issues at the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility, Vermont’s only women’s prison, seems never-ending.

“By any objective evaluation, it is a horrendous place,” said Troy Headrick, a representative for Chittenden’s 15th district.

However, for incarcerated women in Vermont, it’s the reality they have lived for months, years or decades.

Tiffany Harrington is an organizer with FreeHer Vermont, a prison abolitionist group fighting for alternatives to incarceration. Harrington spent a total of 15 years incarcerated at CRCF, during which she gave birth to two children.

In Harrington’s time at CRCF, she experienced conditions that left her and her fellow inmates with lifelong physical and emotional consequences, including abuse from staff and life-threatening medical neglect while pregnant, Harrington said.

Both staff and inmates in Vermont state prisons exhibited high rates of anxiety, depression and PTSD, according to a 2022 report from the UVM Justice Research Initiative.

There is consensus across the political spectrum that the current facility cannot continue to exist. However, what comes next is where the controversy lies.

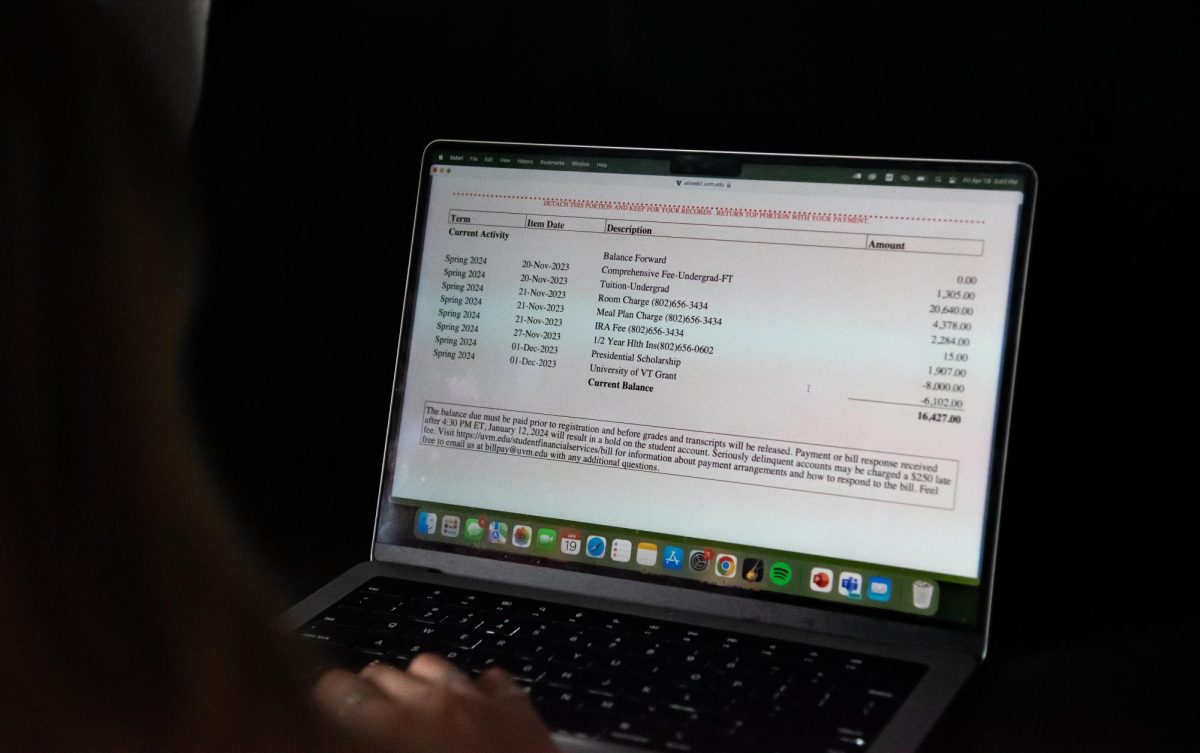

Vermont Governor Phil Scott’s administration has introduced plans for a new women’s prison to replace the existing facility, which currently holds 111 people, according to a Jan. 23 Vermont population count.

The new prison, which would take over 10 years to build, is estimated to cost over $70 million, though numbers from the Scott administration estimate that it may end up being double that amount, according to a March 1, 2023 letter from the American Civil Liberties Union to Vermont state legislators.

Though proponents of the prison say it is a necessary step to improving conditions for incarcerated women in Vermont, critics say the tens of millions of dollars going towards a new prison should be focused on rehabilitative, non-carceral services instead.

“More often than not, the people in our prisons are victims of poverty, violence, substance use or mental health struggles that don’t have access to the same safety nets that the rest of us do.” said Jayna Ahsaf, an organizer with FreeHer Vermont.

(Courtesy of Corey McDonald | Vermont Community Newspaper Group)

FreeHer is an abolitionist group founded and led by formerly incarcerated women and their allies fighting to end women’s incarceration in the U.S. FreeHer is part of a larger coalition The National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, which was founded in 2010.

Their advocacy work is currently focused on decriminalization and decarceration efforts in New England, as these states have the lowest numbers of women in prison nationwide, according to the Council’s website.

Jayna Ahsaf graduated from UVM in 2018 and is now a full-time organizer with FreeHer Vermont, a position she calls her “dream job,” as it allows her to play a central role in working to change the United States’ criminal justice system, she said.

Ahsaf’s lived experiences, as well as learning more about the work of Black abolitionists like Angela Davis and Mariame Kaba during the height of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, pushed her towards the prison abolition movement, she said.

“I’m a Black Puerto Rican queer woman,” she said. “Many of my people filter in and out of the prison system. I come from generations of folks that have struggled with substance use, so I feel like I had a really personal understanding of what happens when community members don’t have the support they need. Usually what’s left to catch them is just prisons.”

When it comes to creating alternatives to the carceral system, Ahsaf wants people to “be more creative” in imagining a future beyond prisons. Smaller, community-based restorative justice programs should serve as an example, she said.

“We have a lot of mini models in this state that we can replicate and build on. So we’re not starting from scratch like a lot of people think we are,” Ahsaf said.

Representative Headrick entered office as a self-described prison abolitionist. Being a politician forced him to strike a difficult balance between idealistic views and “legislative pragmatism,” he said.

Headrick is a representative for Chittenden’s 15th district, which includes Central and Trinity campuses as well as surrounding areas. He is one of two progressives on the House committee on Corrections and Institutions, which has overseen the introduction of plans on the construction of the new women’s prison, he said.

Prior to being elected in 2023, Headrick worked with the UVM Center for Student Conduct for almost 15 years.

“When Angela Davis asks, ‘Are prisons obsolete?’ my answer is that yes, we should be a society that doesn’t need prisons,” Headrick said. “Philosophically I am very aligned with the FreeHer movement.”

Despite this, Headrick says that being a politician requires him to be prudent.

“There is a legislative appetite to build a new facility,” Headrick said. “My job, as I see it right now, is to communicate with advocates and do my very best to make decisions that are well-informed by evidence by the folks who are on the ground in those buildings.”

Heather Newcomb works within the women’s correctional facility as the Women’s Program Manager for Justice Involved Services with Vermont Works for Women, where she helps women who have been involved with the criminal justice system prepare for and succeed in the workforce.

Newcomb’s lived experiences with addiction, recovery and living in poverty have deeply informed her work and support for restorative justice, she said.

“Having a new facility for those women is very important, and I don’t think judges are gonna stop sending people to incarceration,” she said. “Even if another judge never sentences another woman to incarceration from this day forward, there are still women here that have sentences to serve out.”

A newer, larger facility would expand the capabilities of Vermont Works for Women within the prison, Newcomb said.

“If we had more space, we could provide more of that hands-on technical training for different careers, whether it be trades or textiles or artistic abilities,” Newcomb said.

When it comes to prospective changes to prison policy in Vermont, Newcomb believes changing the culture around prisons is more important, she said.

“I think culture eats policy for lunch,” Newcomb said. “I really think it has to do more with the culture of corrections.”

(Coutesy of FreeHer VT)

Though Ahsaf, an organizer with FreeHer, is appreciative of initial efforts of lawmakers like Representative Headrick to listen to the voices of opposers of the new facility, she believes more should be done, she said.

“I know prison abolition is viewed as a radical school of thought, but it doesn’t mean we don’t deserve to be heard,” Ahsaf said. “[Lawmakers] need to hear more from people with direct experience with the carceral system.”

Proponents of the new facility have frequently cited the many services the facility would have to offer, as well as the consideration that will be taken in its design to make it “cozier and trauma-informed,” Newcomb said.

A trauma-informed approach to prison building design emphasizes creating a space that does not perpetuate, but minimizes the existing trauma of both a prison’s inmates and staff.

“There are so many folks, especially in the women’s facility, who are there because of the social situation that surrounds them,” Headrick said. “They enter that world already traumatized, and when we don’t create buildings that seek to improve that, I think we have failed.”

Ahsaf, however, was critical of the term “trauma-informed prisons,” she said.

“Especially in this movement, the opposition almost hijacks our terms and uses them against us,” Ahsaf said. “To me and the women I’ve spoken to that are formerly incarcerated, there’s no such thing as a ‘trauma-informed prison.’ Just adding natural light, fresh paint, yoga programs–it doesn’t remove the inherent trauma of being incarcerated.”

Harrington also rejected the idea of “trauma-informed prisons,” she said.

“That’s bullshit,” she said. “Do you have any idea how much PTSD I have, other people have, just from the incarceration itself? It’s unbelievable. It’s disgusting. It’s a whole mental situation of its own. It’s really sad. ‘Trauma-informed’ is not putting somebody in jail.”