The real story of Andrew Harris

The sign UVM has dedicated to Andrew Harris, the first Black person to graduate in the year 1838, does not detail the way the UVM community treated him while he was enrolled in the school.

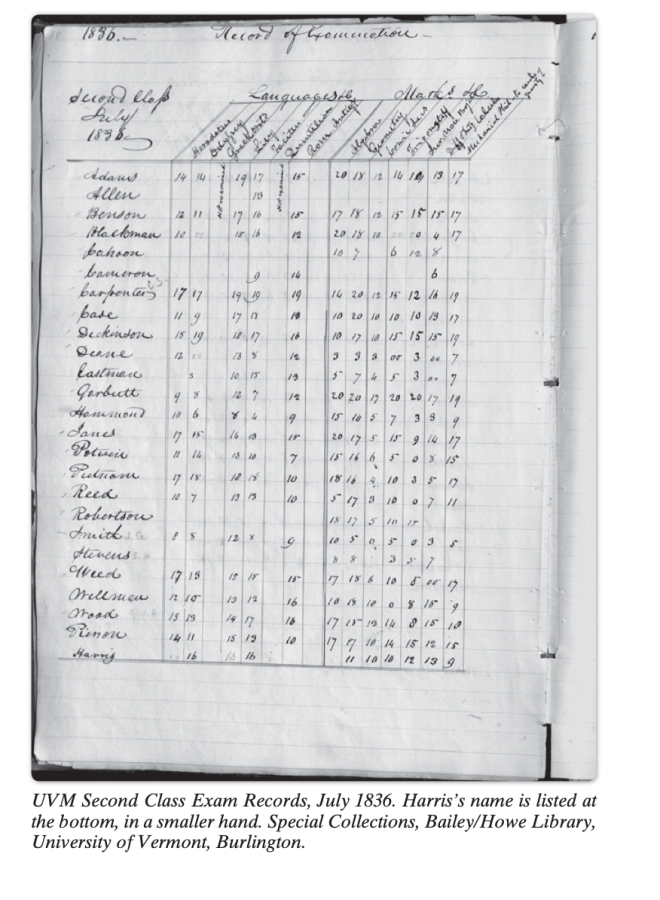

Among UVM’s mistreatments of Harris during his time at the University, administration often listed him last on class rolls and denied him the ability to attend his own graduation, according to one of several articles about Harris by Kevin Thornton, a former American history lecturer at UVM.

Members of the local community resisted and students threatened to boycott classes Harris attended, when he enrolled in the University in November of 1835, according to Thornton’s article published by the Vermont Historic Society in fall 2015.

“The majority of the class refused to attend graduation if Harris was allowed the privilege that every graduate received in those days,” Thornton said. “The administration [caved] on that and Harris [was] unable to attend his own graduation.”

Although Vermont outlawed slavery with its first constitution in the year 1777, slavery persisted nationwide until the passing of the 13th Ammendment in 1865, according to National Geographic resource library. This happened 27 years after Harris graduated.

Thornton submitted the application to feature a commemorative sign of Harris and wrote the text meant to honor Harris’ life and the time he spent at the University, said Laura Trieschmann, state historic preservation officer.

In 2015, The Vermont Division for Historic Preservation worked with UVM to create the sign in Harris’ honor. However, the Division was dissatisfied with the original location assigned to the sign, which had low visibility on the Pomeroy Walkway, she said. UVM moved it in 2018 to the Andrew Harris Commons.

When the sign was placed in its initial location, Thorton said he felt disappointed with the relatively low traffic of the area. He had recommended the entrance of the Howe Library when he first proposed to set up the sign in 2015 and did not know why it was originally placed elsewhere.

The sign now stands outside the Davis Center that students walk by every day.

After the relocation, UVM named the Commons after Harris, and more recently unveiled a marble monument in Harris’ honor, according to an Oct. 9, 2018 UVM Today article.

The change came several months after Thornton published his second Vermont Historical Society article in 2018, he stated in a Feb. 1 email.

Thornton criticized the original placement of the sign, as well as the University’s failure to deal with the less pleasant parts of Harris’ story.

“Just as in the 1830s, the people running the University today apparently find it far easier to think of Harris as a symbol than as a person,” Thornton stated in his 2018 article. “When I successfully petitioned the state of Vermont to erect a roadside historical marker to him, the university’s administration placed it at the back of a parking lot.”

Before approving his draft for the commemorative sign, the University insisted the phrase “University of Vermont” be included on the sign, Thornton said.

The sign stated Harris was an abolitionist, advocate for Black equality, first African American graduate from UVM and one of the first African Americans to earn a college degree.

“He was a featured speaker at the 1839 meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society,” the sign stated. “Harris was one of the founders of the American & Foreign Anti-Slavery Society [and] a delegate to the first convention of the Liberty Party.”

The signs can only hold 765 characters, limiting how much information can be included, Trieschmann said.

“He was a really admirable person, very concerned with promoting education among Black people, and very concerned with the struggle for equal rights,” Thornton said. “That’s what I wanted to emphasize. I didn’t want to talk about struggling at UVM and that wouldn’t have fit on the sign anyway.”

Harris’ story was central to the story of the University and should be presented as such, said Leon Walls, a professor in the College of Education and Social Services and an instructor for one of UVM’s D1 course offerings, Race and Racism in the U.S.

“Only one message should be sent about this individual,” Walls said. “And it is that he was a very courageous man, first of all. And it’s unfortunate we don’t really know a whole lot about him, we don’t have any pictures of him.”

Harris graduated after three years, then became a Presbytarian minister in Philadelphia where he advocated for the immediate abolition of slavery. Harris remained there until his untimely death at age 27 resulting from a severe fever, three years after his graduation, Thornton said.