“Love Lies Bleeding” is the latest in lesbian cinema, a genre where, typically, you take what you can get.

Personally, though, I felt this movie went above and beyond my expectations. Out of all the admittedly few films I’ve seen about queer women, this one is my new favorite.

Overall, the reception among the community has been overwhelmingly positive—Kristen Stewart is reason enough to love it. But I also discovered that a small portion of the audience took issue with the movie, claiming that it catered to the “male gaze.”

When the male gaze is at work “women in the media are viewed from the eyes of a heterosexual man,” according to an Oct. 27, 2015 Film Inquiry article. It’s a covert but powerful force which reduces female characters to objects that facilitate men’s desires.

The male gaze is pervasive, even in media that doesn’t center men and heterosexual relationships.

Media fetishizing lesbians is widespread; leagues of pornography sites advertise “girl on girl” content and—unlike the title might suggest—their target demographic is not girls.

What could be hotter to a straight man than not one, but two women?

Unfortunately, most well-known lesbian cinema tends to be rife with the male gaze.

For example, “Blue is the Warmest Color,” which was the forerunner of the genre for a long time, features a number of extremely explicit and lengthy sex scenes—one of which is drawn out for almost seven minutes.

Hot-and-heavy sex scenes are not a crime in themselves, but the movie’s use of the camera positions the audience as a voyeur. Critic Manohla Dargis observed that the film felt more about the director’s desires than anything else in a May 23, 2013 New York Times review.

Most damning, there were no queer women involved in the creation of the film. It was directed by a man and led by two straight actresses. Their depictions of lesbian sex are entirely imagination. After a bit of “research,” I can affirm: it feels like watching porn.

The male gaze is especially a concern in depictions of lesbian relationships. The only representation that escapes questioning is completely wholesome and desexualized—the sort frequently featured in cartoons—often resulting in queer adult women clinging to media intended for children.

Consider examples like Marceline and Princess Bubblegum from “Adventure Time,” whose most intimate moment in the series is a kiss during the finale. Similarly, Catra and Adora from the 2018 She-Ra reboot share one kiss in the whole show despite being the series’ primary draw.

“Love Lies Bleeding,” in contrast, was directed by the talented Rose Glass, features two queer leading ladies, and doesn’t shy away from the characters’ sexuality. Still, it faces accusations of the male gaze.

It seems that if a movie depicts women in a sexual context, it will inevitably be deemed as catering to men.

In trying to understand what makes people sense the male gaze in “Love Lies Bleeding,” I turned to TikTok, and I noticed a common theme among the criticism.

Legions of women reported watching the movie alone in a movie theater full of men. One showing even ended with a man arrested for masturbating, according to a March 15 AVClub article.

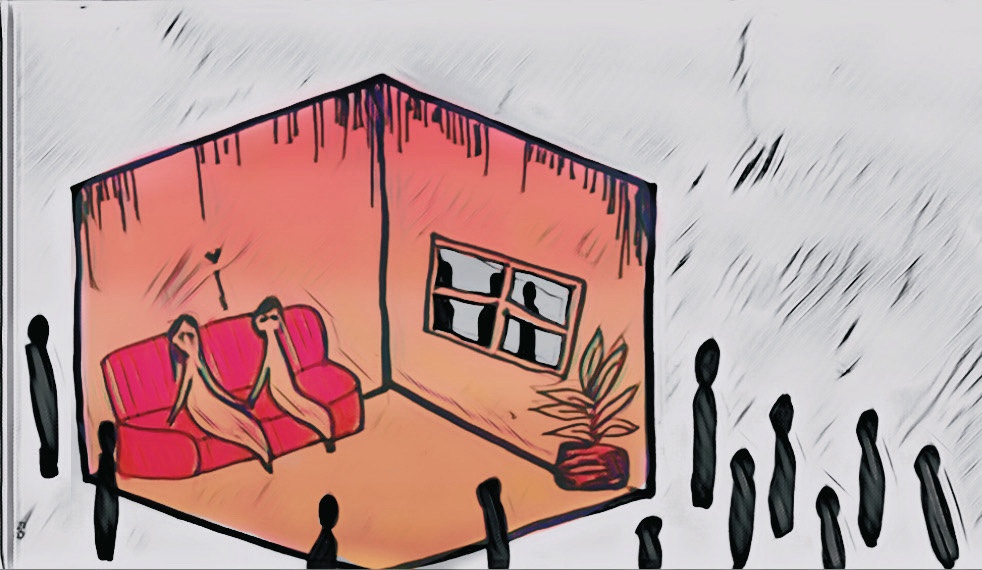

Maybe it’s not “Love Lies Bleeding” itself that contains the male gaze, but the theaters in which we watch it. Even while watching alone at home, queer women sense the sexualizing and objectifying gaze of male audiences.

We internalize their gaze and, in turn, try to shut down our own sexuality before it can be ripped out of our hands by force. It seems the only way for lesbians to exist without being sexualized is by not being sexual at all.

Of course, self-censorship is not the solution.

It should not be women’s responsibility to curb the objectification of their own bodies. Changing the state of the film industry is a tall order, and one that I don’t think the average queer filmmaker should be expected to solve.

I will say this: gay women deserve representation, both sexy and wholesome, and shouldn’t suffer because straight men think our bodies exist for their enjoyment.

Despite the legions of genuinely fetishistic content, there is good lesbian representation out there.

If you haven’t seen “But I’m a Cheerleader” already, drop everything and go watch it right now. It’s effortlessly funny, heartfelt and steamy moments aplenty.

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” is extremely conscious of the audience it appeals to and was one of the first mainstream films that attempts to cater to the “female gaze.”

I don’t want to recommend too many movies I haven’t watched personally, but here’s my wisdom: if you aren’t dead set on having explicit representation, movies with queer undertones sometimes do a better job than the deliberate ones. I suggest giving “Jennifer’s Body” a try.

Despite the male dominated industry, there are filmmakers like Rose Glass out there actively breaking the status quo. We deserve to make movies for ourselves, irrespective of how men will interpret them.