There is a linguistic discontinuity in Burlington’s descriptions of drug culture: students at UVM are “users” of substances, while unhoused individuals downtown are “junkies.”

The “junkie” label reinforces a dehumanizing stereotype of the impoverished and unhoused, demonizing their behaviors, according to a Nov. 27, 2023 Invisible People article. These behaviors are largely seen as acceptable when committed by those living in the “higher class.”

The cruel descriptions I have overheard classmates use in reference to people experiencing homelessness downtown have disturbed me. I often hear the homeless described as “disgusting,” “unpredictable” and “dangerous.”

An increasing number of students have even been avoiding going downtown.

“I can’t even go to Church Street anymore, it’s so bad,” said an overheard student.

Descriptions like these are void of empathy and add to Burlington’s increasing societal polarization. This villainization is driven by harmful and exploitative rhetoric, as seen in posts by the Instagram page @burlington_looks_like_shxt.

The normalization of this language creates an “us” and a “them:” “us” being respectable college students with bright futures and “them” being people who are unrespectable and pitiable. Their humanity is largely unseen.

The American Addiction Center published a report that indicated using drugs as a coping mechanism for stress and loneliness was the main factor behind increasing rates of substance abuse among college students.

In a similar report by the same organization, they listed stress relief as a major contributing factor to drug addiction among the homeless.

As a society, we often fail to recognize the economic and social structures that cause people to resort to substance abuse. Increasing drug use and addiction rates among both groups reflect the increasing severity of the mental health epidemic, proving we are all affected.

Many of us forget that Burlington is not “ours” — it does not belong solely to anyone. A widespread pattern of impunity only worsens this sense of entitlement.

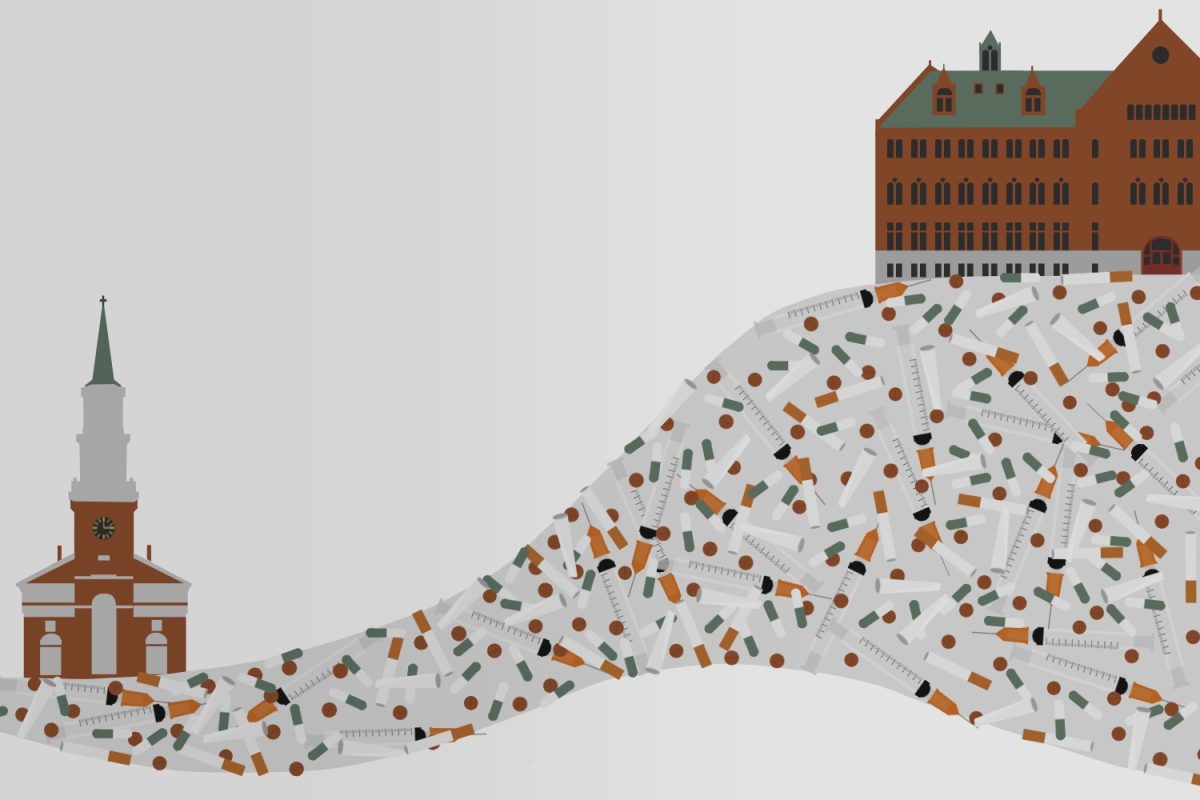

The location of UVM atop a hill, looking down on the rest of Burlington, reminds us of our disconnect from much of the city, both literally and metaphorically. Much of the student body doesn’t acknowledge their privileged place in the community, and years of history and nuance are not considered by those who criticize its current state.

We arrived at UVM and immediately rested our bongs in the window and threw “brat” themed parties, where party drug culture has a much larger appeal than listening to D.A.R.E and “just saying no.”

An NPR article about opioids on college campuses reveals that we are not as separated from the issue as we previously believed. Their data confirms that the overdose death rate among young adults ages 18 to 24 spiked 34% between 2018 and 2022.

They equate this to the rising usage and availability of opioids like fentanyl, which has been found to contaminate other drugs, casting a larger net of victims in the broader community.

“In short, casual or even inadvertent drug use is now far riskier, killing a broader range of people, many of whom may not even realize they’re ingesting opioids,” stated the article.

While hiding in our clouds of escapism, we neglect to address that the epidemic is no longer sequestered downtown; it is knocking at our door.

People do not intend to become addicted to drugs. People also do not intend to live on the streets. Still, as housing costs and shortages continue to rise in cities like Burlington, many, including students, have no choice, according to a May 3, 2021 VTDigger article.

Laura Hardin, a student at St. Michael’s College, had been searching for a room in Burlington for over three months when she was interviewed, according to the article.

“I’ve explored, I feel like, every option,” she said.

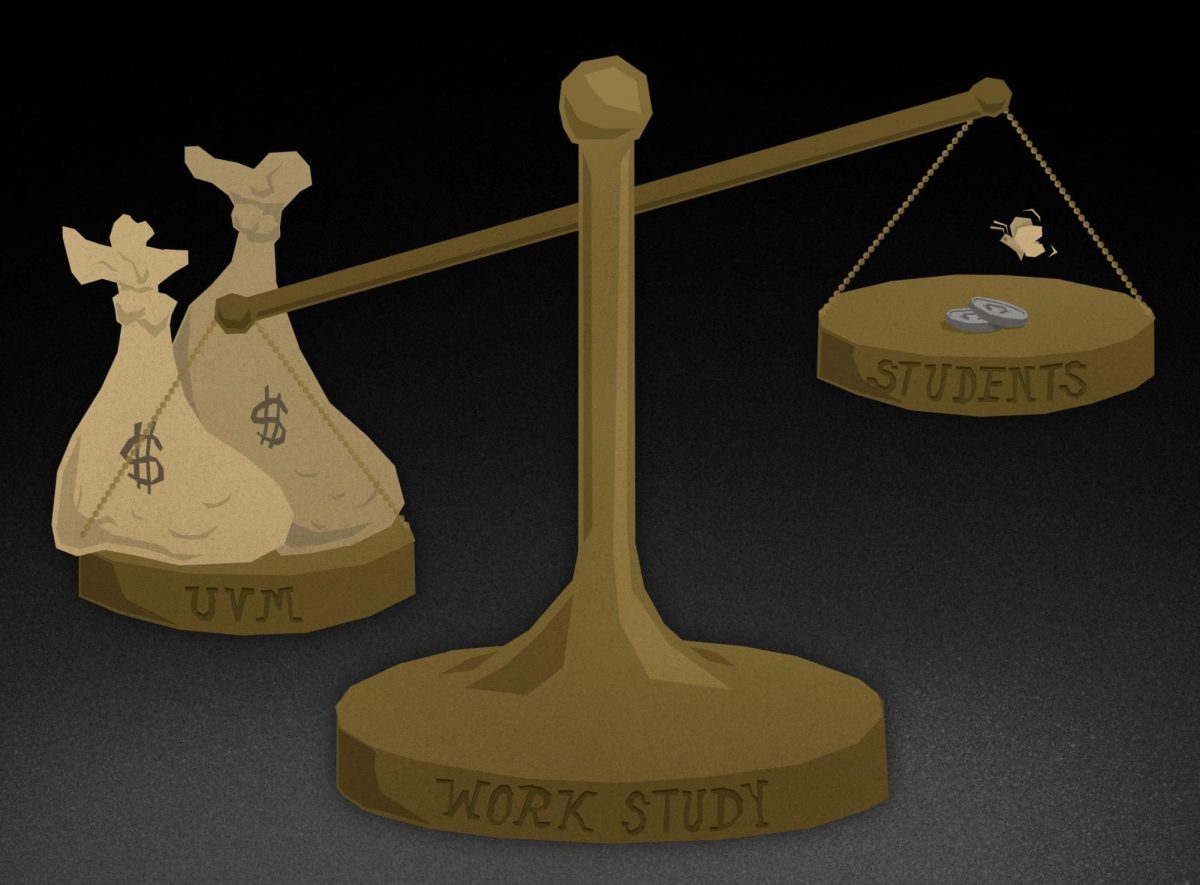

In recent years, almost 90% of families with annual incomes below $20,000 spend 30% of their income on housing, and 60% of families with incomes between $20,000 and $50,000 also spend 30%, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Additionally, many employers require a permanent address on applications and frequently disregard applications from the homeless. A lack of transportation and internet access also add to the difficulty of maintaining a job while unhoused. Without a steady income, overcoming homelessness in this economy is exceedingly difficult.

Homelessness is not a choice, it’s a systemic issue.

An estimated one-fifth of people experiencing homelessness struggle with addiction. As previously stated, this is often a result of substances being used as coping mechanisms for stress, trauma or mental illness, considering half of all homeless substance abusers have severe psychopathologies, according to a Feb. 14 Addiction Group article.

When I walk down Church Street, I can only imagine how much these marginalized communities desire to be seen again as shoppers rush past them, trying hard not to look.

A few months ago, my friend Ashley and I were walking back from eating breakfast at a nice diner downtown when we saw a man lying face-up on the concrete, motionless. We quickly called 9-1-1, and Ashley, being an emergency medical technician, thankfully knew to turn him to his side, as it was evident that he was overdosing.

Ashley felt his pulse, and it was weak, but he began to respond after a few minutes of questioning and tapping. When the firemen came, they checked on the man and informed us that he seemed to be stabilizing and no Narcan was needed. They were glad we had noticed him and responded when he did.

At UVM, many students blame people like the man on the sidewalk for Burlington’s perceived deterioration and overall decline. The privileged often look at the struggle of the marginalized without regard, hardly seeing them as people but rather as something lesser than themselves.

When the man on the concrete began to gain consciousness and talk, one of his friends happened to come along. His friend made sure he was alright, helped him back up and they slowly walked away together.

UVM students see homelessness, poverty and addiction downtown, and rather than trying to look out for those most in need, which could simply be acknowledging the marginalized with empathy, have further distanced themselves.

It is time to acknowledge how our prejudices, apathy and complacency perpetuate this harmful dichotomy. The man’s friend acted immediately and jumped in to help his friend, a fellow human being in need.

The Vermont Cynic accepts letters in response to published material, as well as any issues of interest in the community. Please limit letters to 350 words. The Cynic reserves the right to edit letters for length and grammar. Please send letters to cynicalopinion@gmail.com.