Last fall, to help cover UVM’s hefty tuition, I took a work-study job — rookie mistake.

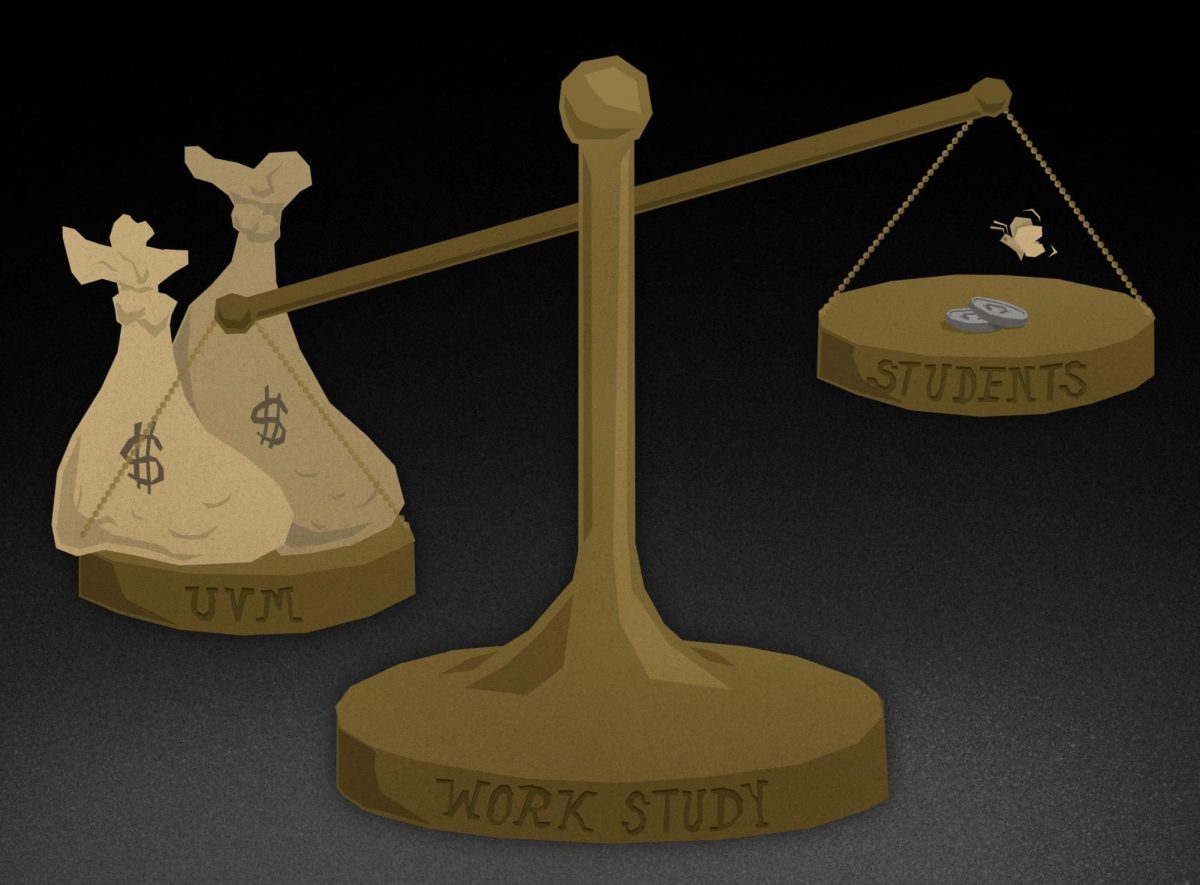

The University of Vermont is known to be one of the most expensive public universities in the country, as both UVM’s in-state and out-of-state tuition costs are nearly double the national average, according to a 2024-2025 college ranking U.S. News report.

However, UVM has been blanketing the flaming fire of student life by dismissing financial insecurity with a work-study job incentive aimed at those struggling to afford the University, myself included.

In theory, work-study jobs are supposed to support students in financial need by granting them federally funded money to work on campus. It allows these students to gain professional and academic experience for their future careers and direct salary compensation to help cover the cost of attendance.

However, this money is not automatically applied to tuition: it is given directly to students in the form of a paycheck, just like a regular part-time job.

The catch at UVM is that the maximum payout for a student’s work-study fund is $3,000 over the course of the academic year, according to the August 2024 UVM Federal Work-Study Program Manual.

UVM’s work-study program covers less than 10% of the total tuition, including housing, for in-state students and less than 5% for out-of-state per year.

Earning this amount would be livable over two semesters if the student wages and work hours weren’t abysmal.

I will credit UVM for following state laws, as our hourly work-study wages went up to a whopping $14.01 this year from $13.67 in 2024.

My experience with federal work-study has been a somewhat positive one. However, until recently, I was only allowed to work a maximum of five hours per week at my job to account for other student workers.

I am no STEM major, but something about working $13.67 an hour, five hours a week, for 15 weeks of the fall semester does not add up. I started to question why UVM makes it nearly impossible to reach our full financial aid potential.

I had the opportunity to interview a coworker of mine, sophomore Lucien Quinones, who works two work-study jobs on campus.

“It’s [the] little I’m allowed to work, and how the award works. It’s hard to make the full award,” Quinones said.

Outside of their job at the Fleming Museum, they work for one of Sodexo’s partnered cafes on campus. This food service company currently employs 423,000 people in the U.S. across workplaces, hospitals, prisons and other universities like UVM.

“[UVM’s Sodexo jobs] have me doing a lot of work that requires specialized skill. I just feel like I’m not compensated adequately for the amount of stress I’m put under,” Quinones said.

Following this, Quinones expressed their opinions on their current wages and the difficulty of making the full work-study award amount.

“I’m a full-time student. I work two jobs, 12-hour work weeks, and it’s still not enough for my tuition needs,” they said. “It is physically impossible in the current way that they’re doing it to reach it with one job at the hours they’ve set.”

Rather than simply supporting the students financially, this additional perspective makes it clear that UVM has alternative motives to federal work-study.

These alternative motives are almost comparable to indentured servitude, a centuries-old controversial and corrupt process that almost always leaves you in some form of inescapable debt.

Instead of paying higher wages for working adults, the University chooses to manipulate student needs by extracting their labor at the minimum wage.

If UVM truly values its students, it’s time to offer work-study jobs that reflect students’ needs and the reality of rising tuition costs, not just add to their stress.

The Vermont Cynic accepts letters in response to published material, as well as any issues of interest in the community. Please limit letters to 350 words. The Cynic reserves the right to edit letters for length and grammar. Please send letters to cynicalopinion@gmail.com.