“Where do people come from and how do they end up where they are?”

English Professor’s book “Old Canaan in a New World” addresses Biblical anonymity

April 30, 2020

Around halfway through writing her book “Old Canaan in a New World: Native Americans and the Lost Tribes of Israel,” Professor Fenton said she struggled to answer the perennial question for people who study literature: why are you doing this?

“Researching this book, I felt like I was on a roller coaster going up a very long, slow incline for a long time,” Fenton said. “Then about two years ago I crested the top.”

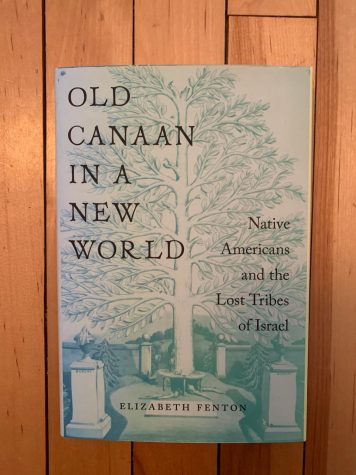

UVM English Professor Elizabeth Fenton’s third book, “Old Canaan in a New World,” was published April 21st, 2020.

The book is a nonfiction history and analysis of what she calls the “Hebraic Indian theory,” the old idea that Native Americans are the descendants of the “10 lost tribes of Israel” described in the Bible.

Claudia Stokes, a professor of early American literature at Trinity University, peer reviewed Fenton’s book and wrote the blurb for the back cover.

“[The book] explores a whole unrecognized and unknown archive, and it’s incredibly extended,” Stokes said. “It spans something like 400 years, or close to it.”

Fenton’s interest in the topic of confused Native American origins arose partly because she found it mysterious.

“It’s a story in the Bible that doesn’t have a satisfactory ending and that makes it ripe for a lot of different kinds of fantasy, a kind of Indiana Jones sort of thinking,” Fenton said.

Fenton stumbled upon the research idea while working on her 2019 book, “Americanist Approaches to The Book of Mormon.” The book of Mormon tells a story of the settlement of the Americas by an ancient Hebrew population, and Fenton said she began to wonder if this idea was singular to Mormonism.

“It turned out the idea that Native Americans were the descendants of a Hebrew population was actually a really old idea, as old as colonialism in the western hemisphere,” Fenton said.

Jeffrey Adams, a graduate student in the English masters program, said the Hebraic Indian theory arose after Anglo-Europeans came across the Atlantic Ocean and encountered Native Americans for the first time.

“Instead of totally shifting their epistemological framework to incorporate indigenous perspectives they were like ‘okay we’ve been basing our whole moral and political existence off the bible, so how can we make sense of this in terms that we already understand?'” Adams said.

Though initially mysterious, “Old Canaan in a New World” took seven years to research and write, a process that Fenton described as sometimes being “painful.”

“Reading 17th century religious treatises about a wrong theory was kind of a slog,” Fenton laughed. “There’s something kind of funny, charming and delightful about this kind of stuff though.”

Fenton said she almost decided to chop the research project up into articles and salvage what she could after it became “stop and go” for nearly two years. She attributes finishing the book to discovering an obscure hollow earth novel called “Beyond the Verge,” which depicts Native America’s as the lost tribes of Israel and describes their descent into the center of the Earth.

“When I found that novel I thought, this is really funny and really weird,” Fenton said. “It gave me a way back into the project and motivated me to finish the pieces I had left hanging.”

After her research was reinvigorated, Fenton said she found part of her books’ modern day relevance in it’s intimate ties with scientific discourse.

“People have used DNA testing to find evidence of Hebraic origins in populations around the globe, and that longing for human origins is never fully separate from religious thinking,” Fenton said. “I think people are hungry for this kind of information and that question, ‘Where did we come from?’ just never stops being interesting.”

Fenton said the idea that Native Americans are the lost tribes of Israel might seem alien to our own time, but it intersects with questions of who belongs in America, or what the relationship between indigenous Americans and colonial settler states should be.

“I think the book, in some ways, provides a set of warnings about the costs of answering these questions badly, or insisting on an answer to these questions, questions that maybe have no good answers,” Fenton said.

American literature Professor Claudia Stokes said Fenton’s book is timely because it can be compared with current debates about immigration and where Americans come from.

“Our current government has put a lot of pressure on American efforts to identify who is American, who is an immigrant to this country, who has a right to be here,” Stokes said. “I think Professor Fenton’s book really shows how those questions have a long and very complicated history that are as old as this country itself.”

Fenton said that the fundamental question, ‘Where do people come from and how do they end up where they are?’ is an old, but urgent inquiry. Though her book cannot provide easy answers, writing about the Hebraic Indian theory was one way for her, as a scholar of early American literature, to address this question.