School is officially in full swing, and so is screen time

Inevitably, the return to class with the onset of the fall semester comes with many changes to daily life—including an uptick in UVM students’ screen time.

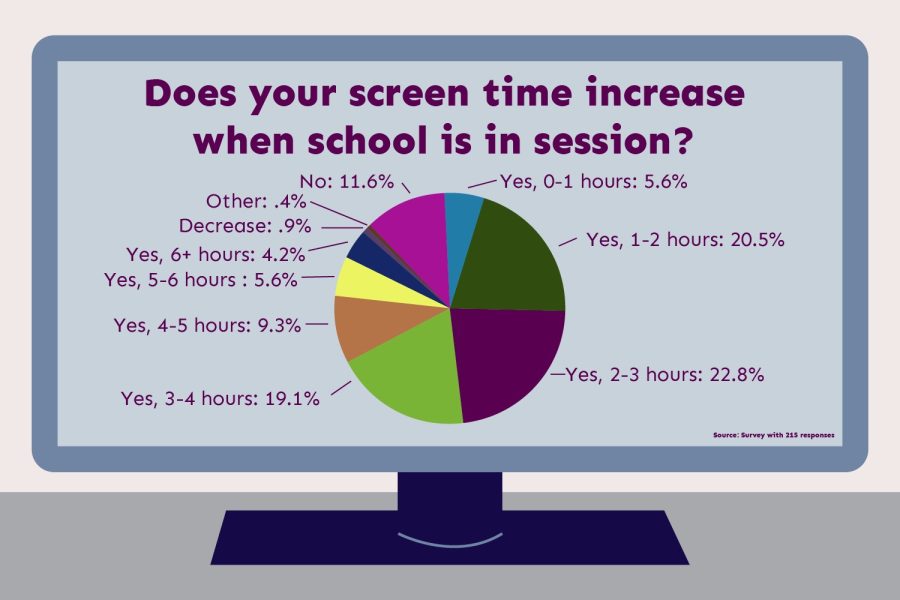

In a survey conducted by the Cynic, many students reported feeling the effects of this increase.

Sixty-five point two percent of 215 UVM student respondents reported school increased their screen time by at least two to three hours a day. Of that group, 20.5% said school increased their screen time by more than five hours, according to the survey results.

Heavy amounts of screen time are strongly linked to poor sleep, decreased energy levels and higher levels of depression, according to the Mayo Clinic.

It is these more serious side effects that make screen time something to monitor. The sudden shift from summer vacation to finding yourself reading 40-plus-page PDFs is an intense one.

First-year Mackenzie Lebuhn particularly feels the impact after having taken a gap year. In high school, she rarely brought her computer to class, but at UVM that has become harder to do.

“Being back in school has really highlighted how much I have to be on my computer, it feels like 24/7,” Lebuhn said. “I walk into class now and every single person already has a computer out.”

Fifty-five percent of UVM student respondents felt the use of personal tech in the classroom made it harder to connect with their peers, according to the survey.

For me personally, computer note-taking has made it increasingly difficult to connect with classmates. During class, many students spend their time texting friends or shopping online.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. Students space out in class, that’s nothing new. But, when attention-lapsing is accompanied by a device, it becomes more difficult to find human connection.

I’m not alone in this observation, either. Professors have noticed it too, specifically in relation to the start of class periods, an opportune time to make connections.

Tyler Doggett, a professor at UVM since 2005, has noticed students keep to themselves more upon arrival.

“Students used to talk much more at the start of my classes than they do now,” Doggett stated. “Mostly, they all just come in and sit quietly, looking at a device.”

As a philosophy professor, Doggett has tried to keep his classes as tech-minimal as possible, continuing to pass out physical handouts and grade assignments on paper.

Many UVM students wish more professors would take on Doggett’s style—86.1% of surveyed students prefer to read on paper instead of on a screen.

The biggest contributor to this preference is burn out, as 64% of UVM students surveyed reported they burn out more quickly while doing their school work digitally.

“There’s just something about the screen that makes doing homework for longer harder,” junior George Bennett stated in his survey response. “I tend to go out of my way to use my notebook for any schoolwork.”

Many students know this feeling—we can only take so much stagnant staring.

This difference in work stamina could be due to an increase in eye strain. Headaches and difficulty concentrating are both leading eye strain symptoms, according to research done by the Mayo Clinic.

The research also found the most common cause for eye strain is reading from a screen without stopping for a long period of time, which is almost impossible to avoid as a student at UVM.

The time adds up, as many PDFs are assigned for digital reading. Perhaps this is why many students want to venture backwards in time—scholastically speaking, that is.

If we were to go back 10 or so years, it would be much harder to find UVM lectures so dominated by Google Docs and other note-taking software. Even with the best intentions, many students get distracted by Chrome’s search bar, where you can find anything.

I myself am no exception. Any time I’ve decided to substitute my notebook for a laptop, I become easily distracted. One moment I’m taking notes on Unit 4, the next I’m updating myself on the Major League Baseball playoff standings.

But, as distracting as it can be, school’s transition to having a greater dependence on tech has had some serious positives too.

The average textbook costs $82.00, according to The National Association of College Stores. Factor that number into the number of required textbooks for classes at UVM and it adds up to a significant cost.

First-year Delaney Hackett said being able to use her desktop to organize each class’s papers has made it easier to get over the fact that she prefers to read on paper.

“Using online PDFs is usually cheaper, plus it’s nice that instead of having to buy all my heavy textbooks I can have them all in one place,” Hackett said.

Not to mention, digitizing an institution where paper used to be an absolute necessity can only help our environment by reducing waste and emissions.

The Earth’s health shouldn’t come at the cost of an enjoyable classroom experience. Tech makes class a less social experience, which is absolutely key to how many students learn.

With less connection amongst peers, study groups are harder to create and bonds are harder to come by. I miss having “class friends,” and Google Docs’ domineering of my neighbors’ desks has played a major factor in the loss of that experience.

The answer doesn’t lie in a complete switch back from digital to paper—rather, we need to have more open and honest conversations about what is sustainable for students and our planet.

When 80.1% of our 215 UVM students surveyed prefer reading on paper, despite the fact that most do their readings online, it’s clear there’s a digital disconnect to reevaluate.

(She/her)

Ellie is a senior public communication major from Manchester, CT. Ellie is also an accelerated Master of Public Administration student. This...