“I’ll do medium spice, just to be safe,” said the server at Central Market Taste of Asia on North Winooski Avenue in Burlington’s North End. I tried again.

“No, I really do want it hot. I liked the curry you made me last time.”

“Are you sure?” she asked. “It has chilies in it.” I continued to emphasize that, yes, this was the level of spice I wanted, and after a fairly lengthy discussion she wrote “Hot” on the order slip and brought it out to the kitchen.

The issues I wanted to address during our discussion concerned whether or not I was doing something unusual. As a white American in a rural state, I realize that members of my demographic had probably come in before and been overwhelmed by spicy dishes— or, suspecting that they might be, had been careful to ask about a dish’s spiciness beforehand. I don’t blame my server, then, for exhibiting a bit of extra caution. Most of those inquiries had probably been followed by requests that the spiciness of an order of shrimp vindaloo or chicken tikka masala be toned down somewhat, to avoid undue discomfort.

On my first and third visits, I had apparently made the mistake of asking that same question. The first time, an otherwise delicious chicken curry arrived completely devoid of the bracing heat I’d anticipated. Its intact flavors were well-balanced and its chunks of chicken thigh were tender, but the lack of fire left me disappointed. I resolved to try again.

The second time, I ordered chicken shahi korma, a creamy curry dish with nuts and vegetables. I requested “hot,” without prefacing the request with any sort of question. I was asked to confirm my choice, and said yes with what must have been the right amount of confidence. The shahi korma was, indeed, blazingly hot. Small orange flecks of chili were visible throughout the pale sauce. On its own, the curry would have approached — but not yet reached — an uncomfortable level of heat. Accompanied by papadums, (thin, shatteringly crisp wafers of legume flour), white rice and pleasantly stretchy naan bread, the balance of heat and flavor was wonderful.

My third visit and subsequent order led to the conversation excerpted above. I had arrived with a question in mind, one I’d been mulling over since the first meal: Had my expectations of Nepalese food been skewed unrealistically toward the fiery side of things? The try-hard Westerner who seeks to prove himself by trying a foreign cuisine at its most “other” is a well-known foodie stereotype. He (for this diner is almost invariably male) is closely related to the seasoning-averse lightweight. Neither will appreciate another culture’s food except on their own terms, and neither is something I’d like to be.

Andy Ricker, a white American restaurateur and Thai food expert known for a nearly unique deference to the culture that created his livelihood, has often suggested asking restaurant staff to “make [a dish] as you would for a Thai person.” He offers a translation of this phrase into Thai; lacking confidence in my off-the-cuff Nepali, I settled for English.

“Would a Nepalese person want this dish to be spicy?” I asked.

“Yes,” my server replied. “Nepalese people like very spicy food.” Whew. Reassured that this order would be the real deal and not just some crass stunt, I thanked her and joined my photographer, Ryan, to look through the shop’s grocery section.

Because we got to Central Market Taste of Asia toward the end of their kitchen’s operating hours, seating was not available and we had to take our order to go. To avoid a similar experience, readers should take note of the fact that Central Market sometimes closes earlier than their sign states (9:00); additionally, the kitchen closes at 8:30 and sometimes before then.

After perusing a burstingly diverse array of pan-Asian produce, packaged foods, and housewares (highlights included coconut-flavored larva-shaped cookies, perfect for Halloween; stark white cans of butane gas labeled with a red and orange explosion graphic and the word “POWER;” and a tall, slim glass bottle of fuchsia-hued “Houston Cowboy” lychee-flavored syrup, product of Thailand, complete with illustrated cartoon namesake– perhaps a placebo substitute for Houston’s better-known purple concoction?), Ryan and I collected our food and ventured outdoors in search of a place to eat.

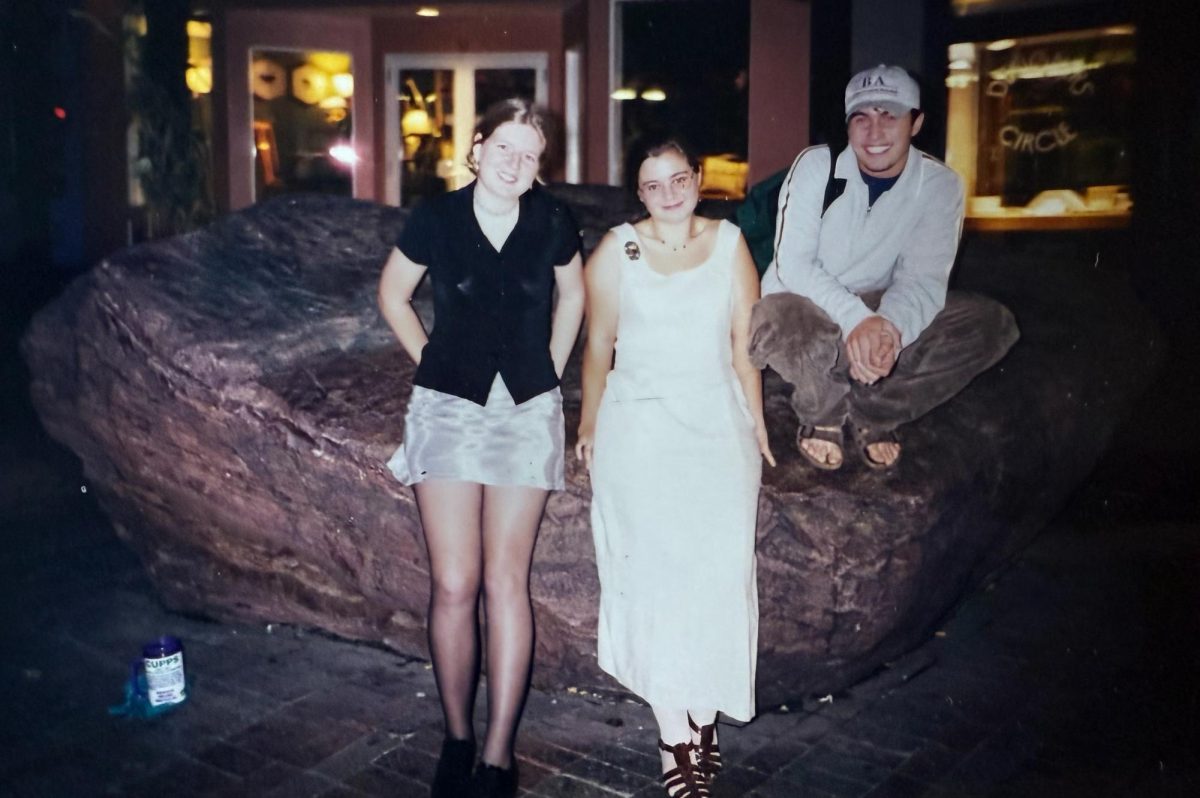

Tungsten streetlights lent a sleazy glow to the Old North End as we walked, and it soon became apparent that our food would grow cold before we found a table with natural lighting. We sat down to eat on the sidewalk by an African market, in full view of passing cars.

The thali platter I’d ordered included chicken and lamb curries, both assertive and complex, with tender and flavorful meat; lentil soup, whose float of orange chilies gave it a fruity, almost floral lift; the aforementioned pappadum, along with poori (a deep-fried whole-wheat bread puffed from within by steam); the creamy yogurt sauce raita, which was sweeter and thicker than Indian versions I’d had in the past; the ever-present white rice; and gulab jamun, a spherical dessert made of milk solids and soaked in cardamom-scented rosewater syrup. All were terrific. Ryan’s order of onion bhaji was enjoyable as well, although a tad greasy. We used part of the substantial portion to improvise a sort of quasi-Nepalese take on poutine, pouring a small amount of curry over the sweet, battered fried onion. It would probably have been better with some paneer to stand in for the traditional cheese curds.

All in all, I’m mostly pleased with the establishment that has replaced 99 Asian Market at 242 North Winooski Avenue. What was once Burlington’s most underrated bowl of pho has given way to an array of rich, well-spiced stews, as well as a number of noodle dishes I have yet to try. There will be plenty of opportunities in the future; already, Central Market Taste of Asia seems likely to inherit its predecessor’s place as an Old North End standby.