Eugenics at UVM: why Abenaki leaders feel the apology wasn’t enough

The book, “Breeding Better Vermonters,” lies open to a page titled “The Quest for a Eugenic Vermont,” April 17.

A shadow looms over an empty space on the wall of Howe Memorial Library where a portrait of former UVM President Guy Bailey once hung next to that of David W. Howe.

Nearly three years ago, Bailey’s name was removed from the Howe Memorial Library following campus-wide outrage over his involvement in the eugenics movement during the 1920s and 30s.

Eugenics, a topic scarcely discussed today, was a movement aimed at cleansing society of Indigenous people and people with traits that had been subjectively deemed “undesirable,” through sterilization.

The targeted groups consisted of Native-American populations, including the Abenaki People, as well as immigrants, women and persons with disabilities, according to a 2019 letter from former UVM President E. Thomas Sullivan.

“At the turn of the 20th century some scientists advocated for the adoption of certain principles that had been discovered by biologists and tried to apply them to society,” UVM sociology professor Lutz Kaelber said.

Many scientists chose to apply the biological principle, survival of the fittest, to society, which caused people identified as unfit to be disregarded, or in the case of eugenics, sterilized, Kaelber said.

“The classic social Darwinist approach [was to] not support people who were considered unfit,” Kaelber said. “Now eugenicists in the United States took that further; they wanted to actively involve the state in deciding who could reproduce.”

Vermont was one of many states to conflate prejudice with poor heredity, leading to the sterilization of residents deemed to be unfit, and UVM played a major role in this process Kaelber said.

“People who were sterilized […] lived in shame because there was a social stigma attached to the conditions that gave rise to their sterilization; sometimes they were poor, or they had been victims of sexual assault and [had] been blamed for that,” Kaelber said.

According to Kaelber, the emotional and physical strain of the eugenics movement could take years to set in.

“Young women were sterilized when they were 15 years old and not even told about the procedure or what it meant,” Kaelber said. “Fast forward 10, 15, 20 years: they tried to have children and they ultimately realized that they couldn’t, and why.”

For Don Stevens, Chief of the Nulhegan Abenaki Nation, a group of Indigenous people who were often targeted by the eugenics movement, the eugenics movement came at the cost of his family heritage.

“My grandmother was listed in the eugenics survey, which caused her to deny her heritage, and she wasn’t able to be proud of that,” Stevens said.

Until the University takes action to deal with the severe impacts of the eugenics movement, it will be hard for many people to move forward.

“What I mean by fixing it [is] saying you’re sorry and then doing things to show that you really mean it,” Stevens said. “Until you do that you’re not going to get a change and it’s kind of sad.”

UVM student group NoNames for Justice highlighted Bailey’s past support for the movement and demanded the removal of Bailey’s name from the library in March 2018, according to an August 2018 Cynic article.

Following the student group’s demands, UVM created a Renaming Advisory Committee in March 2018 in order to look further into Bailey’s history with eugenics at UVM according to an August 2018 Cynic article.

Both the UVM Renaming Advisory Committee and the Board of Trustees voted to remove Bailey’s name in October 2018.

However, three years later, questions are being raised about whether this was the right decision and what more could still be done.

To Stevens, the name change was unnecessary.

“You don’t always need to change the name because when you change a name, you forget about it because it’s not visible anymore,” Stevens said.

Stevens believes there were better alternatives that provided educational opportunities about eugenics as opposed to taking Bailey’s name down completely.

“Instead of renaming it to something else […] and in five years nobody will remember this was a controversy, it’s better if you left the name but put up informational signs, or websites to explain what that professor or that person’s role was when they were at the college,” Stevens said.

Although the UVM administration didn’t follow up the removal of Bailey’s name with any educational outreach, they did submit a formal apology to those affected by eugenics in 2019.

Sullivan issued a statement to the UVM community in June 2019, recognizing UVM’s participation in eugenics and apologizing for the suffering it may have caused members of the Vermont community.

“It is fitting that our institution express its deep and sincere remorse for support given to the eugenics survey and associated conduct in Vermont,” Sullivan stated. “We recognize and deeply regret this profoundly sad chapter in Vermont and UVM’s history.”

Sullivan wrote that the UVM community should move forward by learning from past mistakes and providing educational opportunities centered on eugenics.

Sullivan stated that moral clarity, among other reasons, drove him to write the 2019 letter, in an April 13 email to the Cynic.

“My statement was based on the historical record, board consultation across the University, a view that we needed a University statement and an apology grounded in moral principles and clarity,” Sullivan stated.

For Stevens and the Abenaki community, the apology was a necessary step in the right direction.

“Before we can move forward with UVM, we need to heal the wounds from [eugenics],” Stevens said. “It’s the right thing when you do something wrong to say you’re sorry, so that way you can fix it.”

However, Stevens has grown tired of waiting for UVM to take further action on the statements made in their 2019 apology aimed at amending their past involvement with eugenics.

“I’m a little disappointed that [UVM] hasn’t followed up,” Stevens said. “I’m not talking about individuals, I’m talking the administration hasn’t followed up with any of the positive things that go with an apology.”

In the past, Stevens had made recommendations to the UVM administration about hiring someone in a full time position to coordinate Indigenous work on the campus in order to help rectify harm caused by the eugenics movement and connect UVM to the Abenaki community.

However, after suggesting this position be made in order to help create a resource for professors and a mentor for students, the school showed little interest, Stevens said.

“I asked them if they wanted to help pay to create a position and they said they don’t [want to] donate to a nonprofit to do that type of thing, or they haven’t decided to create a position themselves,” Stevens said.

This was a disheartening response for Stevens, as he assumes no change will come until the administration takes action.

“We can’t force UVM to do anything, we can ask, but no significant actions will ever happen until the administration [or the Board of Trustees] decides to put their weight behind it,” Stevens said.

Kaelber agreed with Stevens’ words when he likened the school’s apology to a cheap medal.

“Someone once told me why soldiers get medals instead of a raise during war: medals are cheap. The same thing [is true] here: apologies are cheap; in fact, they don’t cost anything,” Kaelber said.

To Kaelber, UVM’s apology was certainly not enough to remedy the emotional toll the eugenics movement took on those it affected.

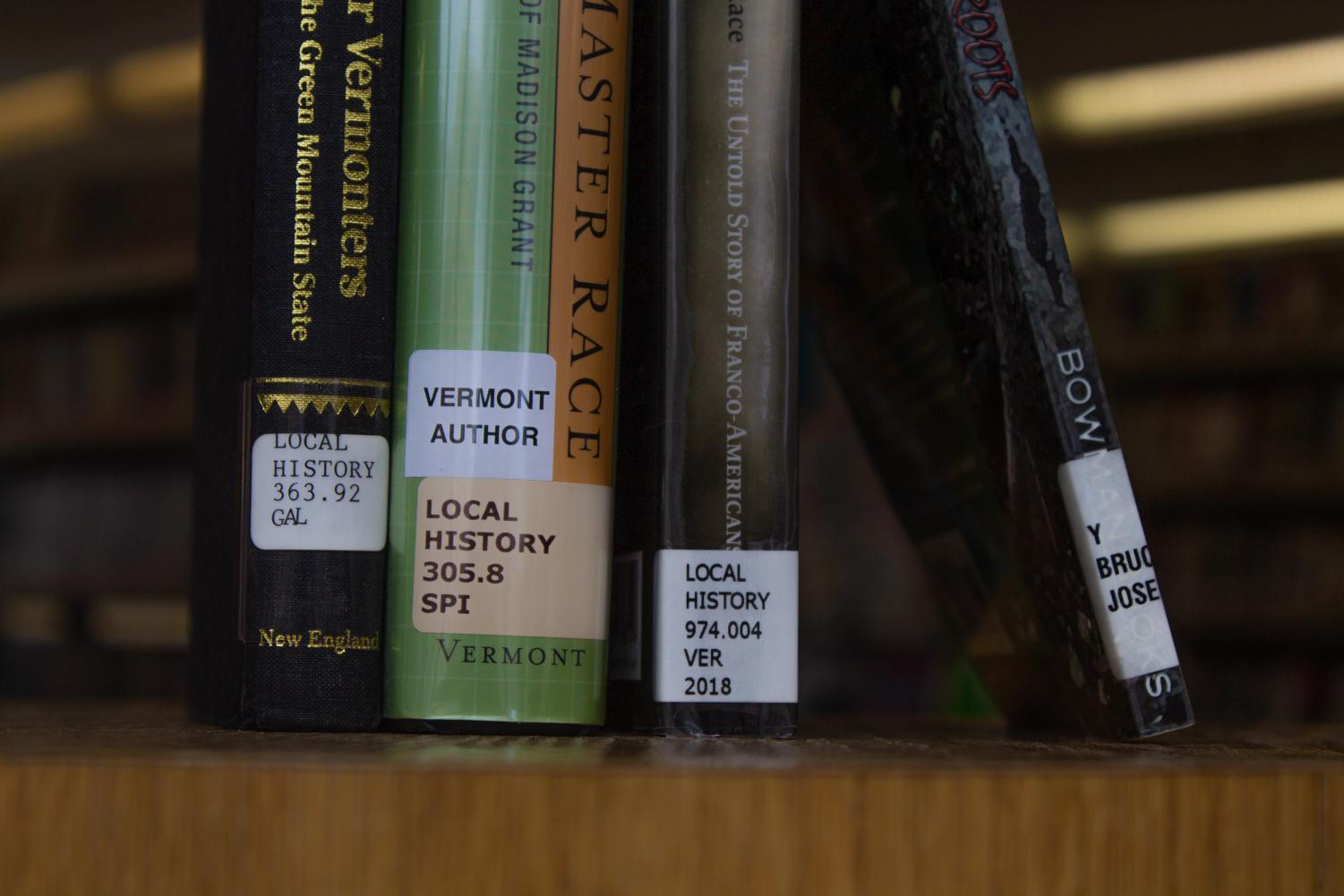

In 1925, UVM zoology professor Henry Perkins created the Eugenics Survey of Vermont, which was first used to collect evidence on sixty Vermont families believed to have bad genes, due to their poor social standing according to “Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History.”

Perkins’ survey identified people who were African American, Abenaki, French Canadian, as well as poor, institutionalized or mentally ill as being genetically inferior according to Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States.

Financial support from then-UVM President Guy Bailey allowed Perkins’ survey and status to take off, and in 1931 Perkins used that status to help support the passage of A Law for Human Betterment by Voluntary Sterilization according to Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History.

This law resulted in 253 sterilizations being performed between 1931 and 1963 on Vermonters who were identified as being inadequate, many categorized by Perkin’s survey according to Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States.

Perkins had close ties to UVM between 1902 and 1945, when he worked as a zoology professor and curator of the Fleming Museum of Art, which strongly linked the school to the eugenics movement.

However Janie Cohen, current curator of the Fleming Museum of Art, said it wasn’t until 1995 that the school publicly began to recognize it’s past involvement in eugenics, which came in the form of an art installation made by Michael Oatman.

“It was both a little worrisome and really exciting that prior to that time, the only thing that had been made public in Vermont about the eugenics movement was an article written by Kevin Dann in Vermont History Magazine,” Cohen said.

Oatman publicized eugenics by creating an art exhibit that was based around Perkins’ time at the school, in which the artist created a space with his laboratory and study.

“The outcome was we had a lot of people saying, we appreciate that this was done through the eyes of an artist,” Cohen said. “It really created a portal and opportunity to understand [eugenics] in a different way.”

The installation began the discussion around UVM’s role in the eugenics movement, with then-master’s student Nancy Gallagher publishing her book on eugenics, “Breeding Better Vermonters,” just a few years later in 1999, Cohen said.

While Stevens believes UVM hasn’t done enough to recognize their role in the eugenics movement, and make amends, he recognizes there have been changes on an individual level.

At the Fleming Museum of Art, these changes come in the form of completely reshaping exhibits based on public opinion and historical accuracy, in order to more holistically represent the pieces being displayed.

“We’ve really spent the last nine months working internally on educating ourselves, and we are now going to begin having conversations within the UVM community and the Burlington community about people’s experiences in coming to the museum,” Cohen said.

Changing these exhibits was spurred by the desire of the museum to better represent historical artifacts collected during the eugenics movement, that were improperly documented at the time.

While Perkins was curator at the Fleming, he collected many artifacts in order to record and track the very cultures he was destroying, Cohen said.

Because of the unethical way in which some of the artifacts were collected, many of the exhibits at the Fleming lack their true cultural context, which has made the process of reorganizing the museum difficult, she said.

This unethical collection process in and of itself also demonstrates cultural erasure, Cohen said.

“Values can get baked into the collections in a way because they were taken in a really extractive way and there was no curiosity about the culture [or] sincere desire to to gain knowledge about it, it was more we’re destroying it so let’s document it,” she said.

Although it is a complicated process to try and contextualize pieces taken during the time of eugenics, and reframe them correctly, Cohen believes with the help of the UVM and greater Burlington community, the museum will reach its goal.

“[Input] is the key thing about how we tell these stories,” Cohen said. It’s not just going to be our staff doing this obviously, it’s got to be broad based it’s got to be a lot of input.”

UVM lecturer Chris Brooks has also been making individual changes in order to better represent the history of eugenics at UVM.

Brooks, who helps teach a class about the environmental history of Vermont, integrated the topic of eugenics into his lectures relatively recently.

“I started teaching about this relatively recently, and I think it’s been really interesting and troubling to take a deep look at this history, but also exciting to address it directly in class […] and figure out how we can reckon with this history and make positive steps forward,” Brooks said.

After teaching about eugenics in class, students have given Brooks positive feedback, and shown that they are very open to learning about the topic.

“I got some positive feedback after that day of class and students just said that they appreciated how we addressed the past history in the state and at our school really directly, so that’s encouraging,” Brooks said.

Brooks believes that educating on the topic of eugenics is important during a time like this because it’s still so relevant in the community.

“I think it’s important to understand that this is really a contemporary issue that we are dealing with right now and to urge everyone in our community to consider what can be done to help heal these wounds,” Brooks said.

Although Brooks concedes that he doesn’t exactly know what to do in order to resolve the pain of eugenics, he believes that students could play a key role.

“I admit that I don’t have a great answer to that question but in my experience, young people generally are at the forefront of thinking in terms of diversity, equity and inclusion, so I would suspect that students have great ideas,” Brooks said.

(She/Her)

Kira Schaefer is a sophomore public communications major from Westchester, N.Y. and is super excited to start as the podcast editor for the...

(He/him)

Eric Scharf is a senior political science major and French minor and serves as the managing editor at the Vermont Cynic. He started at the...