VT Supreme Court rules against UVM, says police document should be made public

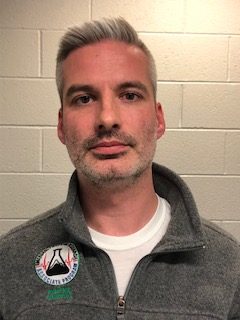

Jacob Oblak (left) shakes hands with UVM’s General Counsel Sharon Reich Paulson (right) just before their case is heard in front of the Vermont Supreme Court.

Vermont’s highest court has ruled the UVM Police Services arrest record should be available to the public despite the university refusing to hand it over.

The Vermont Supreme Court issued their ruling in favor of appellant Jacob Oblak, a recent graduate of Vermont Law School, Aug. 23 after Oblak argued in front of the court in May.

Oblak is suing UVM for access to a document that explains what evidence UVM Police Services had for arresting then student Wesley Richter in 2017. Typically, a document of this kind qualifies as a public record under Vermont law, but UVM argued because the case against Richter was dropped it’s a sealed court document.

The Vermont Supreme Court disagreed.

Oblak made a public records request through the University for access to the document as part of a project he was working on about the intersection of free speech and hate speech in March 2018.

Richter was cited for disorderly conduct after he made a racial threat in Howe Library while talking on the phone, but the case was dismissed by a Burlington judge for a lack of probable cause, according to court documents.

Oblak is fighting one year later for the document because he believes it’s crucial to set an example for the sake of democracy, he said.

“I filed this lawsuit because I believe that democracy requires transparency of government and patterns of government secrecy are antithetical to a free people,” Oblak said.

The incident was widely reported on by media across the state. But the press and the general public still don’t know what exactly Richter said in the library or why the judge felt prosecutors didn’t have enough evidence to move forward, and they ought to, Oblak said.

“I don’t see how the public could possibly oversee its government agents if the public is prevented from understanding why its police choose to arrest [someone] and why its prosecutors decided to prosecute,” he said.

The court ruled that because the document was created by UVM Police Services in the course of its business as a public agency it’s best characterized as an arrest record, which is available to the public unless otherwise sealed, according to court documents.

The University will continue to fight the decision, UVM Spokesman Enrique Corredera said in a statement to the Cynic.

“The decision does not bring the case to a close. The court sent the case back to the Superior Court. The University will ask the lower court to give consideration to other Public Records Act exemptions.”

In UVM’s initial response to Oblak’s request, public records keeper Vice President Gary Derr cited the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act, Vermont law and claimed the incident was still under investigation, according to court documents.

But FERPA doesn’t ever apply to campus public safety agency records public records law expert Frank LoMonte said.

“If a college is claiming FER- PA requires them to remove student names from police reports, they’re just dead wrong,” LoMonte said. “I mean that is not a gray area. That is a black and white area.”

A new court date has not yet been set for Oblak’s case.

Sawyer Loftus is the News Editor for the Vermont Cynic. He is a junior History major with a passion for News. This past summer he was an intern in the...