UVM Political Science professors discuss historic election and what’s to come

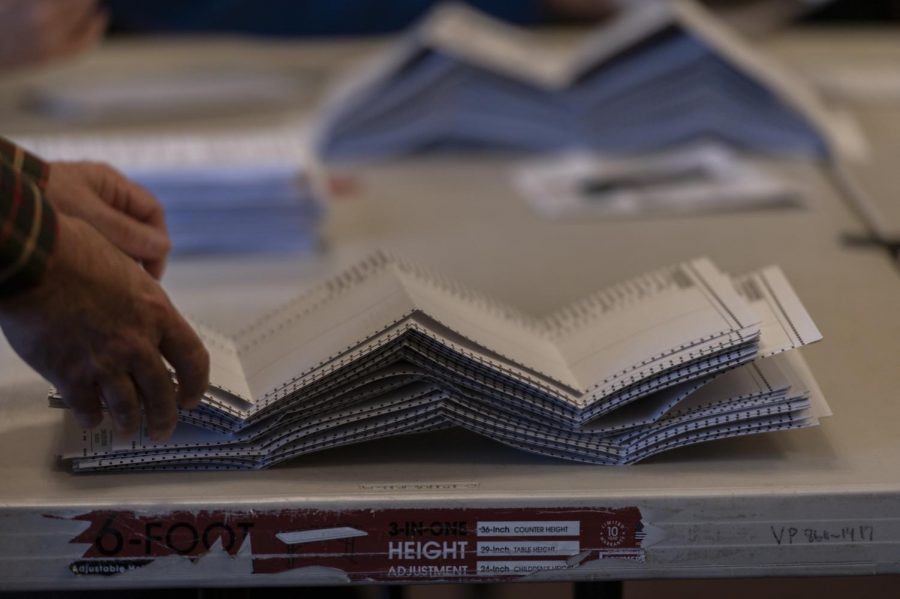

One of the team members of the Ward 7 cohort stacks the received ballots, preparing them to go through the ballot counter Oct. 29.

UVM political science professors discussed what Americans could expect in the coming weeks, including increased division, further actions by President Trump and the media’s role in it all.

During a public panel for the UVM community Nov. 5, Professors Alec Ewald, Ellen Anderson, Jack Gierzynski and Tom Sullivan talked about party division and the role of the Supreme Court going forward.

In an interview Nov. 7, Professor Lisa Holmes discussed how the U.S. got to such a divided place.

Here are some of their most important points and answers:

*These questions were asked and discussed before Democratic Candidate Joe Biden was announced as the winner of the election Nov. 8.

Is there a chance that Trump could go to the Supreme Court over this election if he loses?

Lisa Holmes: Well, he keeps saying he is going. And he could certainly petition the Supreme Court on appeal to ask them to hear a case. That doesn’t mean that they’re going to hear it, though. Even if they take the case, they will not rule one way or another on the merits of the case.

Clearly, Republicans are thinking about this. But at the end of the day, one of the reasons why justices have lifetime tenure is so they are not beholden to the president who put them there. So I think if the Trump administration is hinting their hopes and dreams of him winning the election on the Supreme Court, making it happen, kind of like what happened in 2000, that this is a gamble that may not pay off for him because he cannot force them to take this case.

A popular opinion of students is that the Electoral College is unfair and should be abolished. What do you have to say about that and can you explain how the electoral college works?

Lisa Holmes: What I will say is that the Electoral College was intended to be an indirect way of choosing the president and it was a way to establish the importance of states as states. The Electoral College has its roots in the tensions between large states and small states at the Constitutional Convention, but also the tension over the slavery issues, so there were very clear reasons why the Electoral College was put in the constitution.

There are a lot of downsides to the Electoral College. One is this concept of the popular loser, where the person who wins the popular vote loses the Electoral College. One upside of the Electoral College is that it keeps election disputes contained within individual states.

What is the potential role of “faithless electors?”

“Faithless electors” are people in the Electoral College who are pledged to vote according to statewide or district popular vote but do not vote that way, according to a Nov. 4 USA Today article. Even if Biden won a state, an Electoral College member could cast their ballot for President Trump.

Alec Ewald: If you refer to the Constitution, it specifically gives state legislators the power to give the electors what to do. But the court just decided that although that is indeed the case, individual electors can’t do whatever they want.

Tom Sullivan: The United States Supreme Court said that the electors can be bound to the legislatures to follow the rules. And if they don’t, they can be dismissed or penalized or sanctioned in some way.

Lisa Holmes: If Joe Biden gets a victory in the Electoral College, just barely, then we might be in a situation where we have to worry for the next few weeks about whether any electors change their votes in the electoral college. That’s highly unlikely to happen. It has never happened before. My guess is that no one wants to live under that uncertainty. The Electoral College actually votes in December.

Is there a possible way to reduce partisan divisions through a multi-party system?

Jack Gierzynski: If you take a look at what the sources of polarization are in our system, and you think about what a multi party system would bring, the Democratic party is probably the most diverse coalition. I’m not talking demographics, I’m talking ideological issues. They need to be that way to build a majority.

The Republicans are a lot more pure and their conservative views for the most part. The Republicans are the ones who had been the least likely to compromise. If you add another party… I don’t think that would be a solution to polarization. It probably would exacerbate disagreements.

Is the media responsible for the issue of polarization, or are they responding to the populace being polarized for other reasons?

Jack Gierzynski: There are natural human tendencies that exist out there. [The media] really engages their audiences to have the sort of antagonism, the nastiness, those things that they draw out because that gets them a big audience. I do think that the media has a big role in really making that, bringing it to the forefront, that exploitation then becomes the media polarization.

There’s a lot of research about negativity bias in the media. That negative coverage really gets a greater audience. So the media is really biased towards negativity. And that feeds that negative polarization, that negativity is in human nature, and the media just draws it out.

Why did not all of the states start counting the ballots earlier?

Lisa Holmes: I think some of this is because of court ruling. Others are because of what the state law actually says in terms of when they can start counting. Its state by state decision based on what state law says and how those laws might be interpreted or affected by court decisions.

Why is this election so divisive?

Lisa Holmes: I would say the bigger kind of longer term systemic reason is that we’ve just become increasingly polarized. Republicans are in their camp, Democrats are in their camp. And increasingly there is negative partisanship, which is when members of both political parties look at each other less as rivals and more as enemies. This is very problematic.

I think it is the single most problematic feature of American politics right now. This predates President Trump and it will post-date President Trump. It’s this bigger problem that we have, and it’s been going in this direction for a few decades now. I would also say that certain individual actors in our political system like President Trump are very adept at exploiting, using our kind of negative partisanship to his advantage.

Is there a way that we can come back from negative partisanship?

Lisa Holmes: It is very clear that Joe Biden is trying to carve a space for that. He keeps talking about the need for the country to come together, find some common ground. I think on one level, he is tapping into something very important, that if this negative partisanship idea continues, or gets even worse, that is very problematic.

But on the other hand, it also strikes me as overly optimistic. This problem is going to go past Trump, whether Trump is no longer President as of January or four years from now, we’re still going to be dealing with things that have caused our two political parties to become more negative towards each other. It’s going to take something bigger than Joe Biden. I don’t know what that is.