Man takes UVM to VT Supreme Court over public records

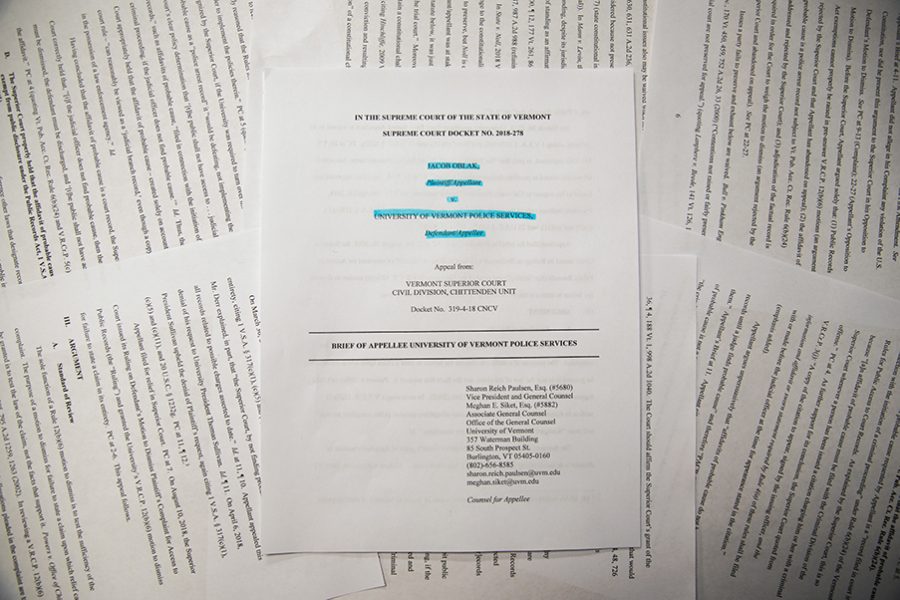

A man is suing UVM in the Vermont Supreme Court to push the University to be more transparent over a student’s arrest.

Jacob Oblak, a law student at Vermont Law School, is appealing his public records case against UVM to the Vermont Supreme Court after a lower court threw out his case. His case is slated to be heard May 15.

Oblak decided to sue the University to push them to be more transparent, especially in a case that was dismissed, he said.

Oblak has to win this case in order to sue the University over naming a police document a confidential education record.

“What is problematic to me is that, if the public is to actually oversee the police, how can the public do that unless we understand why the government is doing what it’s doing?” Oblak said.

The case started a year ago when he filed a public records request for a school paper with the University to see a UVM police services affidavit, a document stating the reasons for arrest, in the Wesley Richter case, Oblak said.

Richter was arrested by UVM police services after allegedly making a racial threat, according to an October 2017 Cynic article. However, a Burlington judge refused to continue the case against Richter in late October 2017, citing a lack of probable cause.

Oblak’s initial public records request was denied by Gary Derr, vice president for executive operations and the person responsible for reviewing all UVM-related records requests, according to court documents.

Derr denied the request cit- ing state law that says a record is exempt from public disclosure if another law identifies it as confidential.

Derr also cited another portion of the law which exempts records pertaining to an ongoing police investigation and exempts “student records.”

Additionally, Oblak’s request was denied citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, making the police affidavit an educational record, according to court documents.

Frank LoMonte, director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida, said there is never a reason under FERPA for a university to deny a police document on the grounds that it is an educational record.

“If a college is claiming FERPA requires them to re- move student names from police reports, they’re just dead wrong,” LoMonte said. “I mean that is not a gray area. That is a black and white area.”

FERPA was created by Congress in the 1970s over privacy concerns of public school students in the U.S., LoMonte said.

In the 1990s, an amendment was added specifying college and university police

department documents are not protected under FERPA, LoMonte said.

“That is black and white, it does not matter that it is university police,” LoMonte said. “I just can’t believe people are taking this position. I mean this has been the law for 26 years or so.”

UVM maintains that the affidavit requested by Oblak was properly withheld, stated Communications Director Enrique Corredera in an April 24 email.

“The Chittenden County Superior Court agreed with the University, and dismissed Mr. Oblak’s case in its entirety,” Corredera stated. “We look forward now to the opportunity to present our case to the Vermont Supreme Court.”

Senior Eli Favro has been working to get access to an unredacted police report after hearing about the difficulties the Cynic faced in getting that same report, he said.

“When I heard about the University, for a lack of a better word, stonewalling on records requests, it kind of riled me up,” he said.

Favro requested access to a police report for a bus accident that happened at UVM Aug. 27, 2018.

The University denied him full access to the report, re- moving names of all parties involved except for police officers, he said.

The reason he was denied was over the same portion of Vermont law that cites “student records” as exempt from public records disclosure.

“They incorrectly cite privacy law and say they do not have to release certain records, such as police reports, and they do,” Favro said. “The law requires them because police reports are public records.”

To him, it comes down to issues over transparency and trust, Favro said.

Oblak’s case is set to be heard by the Vermont Supreme Court 10:30 a.m. May 15 in Montpelier.

Sawyer Loftus is the News Editor for the Vermont Cynic. He is a junior History major with a passion for News. This past summer he was an intern in the...

Alek Fleury is an English and Political Science double major from New Jersey (the greatest place on earth). He dedicates most of his life to being the...